Our history: Classics on the Strand and beyond

Image: The Department of Classics today, viewed from the Strand

Image: The Department of Classics today, viewed from the Strand

Classical subjects have been taught at King's since the College opened its doors to students in the autumn of 1831. The Department now occupies a set of buildings at the north-east edge of the Strand Campus, on the corner of the Strand and Surrey Street, facing Bush House to the north and St Clement Danes and the Royal Courts of Justice to the east.

Only one of these (No. 169 Strand) was purpose-built for College use, in 1928-30; the other two, 170-171 Strand, are early twentieth-century commercial blocks that were incorporated into the Campus after World War II.

The classical connections of this location, however, go back rather further and serve to underline some of the strengths of King’s Classics today.

Saving Classical Art

Image: The Elgin Marbles in Aldwych tube station

Image: The Elgin Marbles in Aldwych tube station

Directly underneath the Department of Classics, running between 169 Strand and Surrey Street, stands Aldwych (formerly Strand) Underground Station, now decommissioned and used mainly for filming (e.g. Death Line, Atonement, 28 Days Later, Sherlock) and as a practice-ground for the emergency services.

It was down here, in the tunnels between Aldwych and Holborn, that a large part of the Parthenon sculptures were placed to save them from bomb damage during World War II. This historic act of preservation finds its modern echo in the work we as a department are now doing to secure the future of the classical heritage in places as far apart as Russia and North Africa.

Making a spectacle

A pride of today’s Department is the annual King’s Greek Play, which brings the ancient world alive on stage each year. This too builds on a local heritage. Before the tube station was built in 1905-7, the exactly equivalent site was occupied by a theatre, opened in 1832 as Rayner's New Subscription Theatre, and subsequently known both as the Strand and the Royal Strand.

Among the many kinds of show produced over the seventy years of the house's life was a line of classical burlesque, represented for example by William Brough's Pygmalion; or, The Statue Fair, which played in the spring of 1867. Before the theatre, the site was occupied by a panorama house, Reinagle and Barker's New Panorama, which opened in 1803 with 360-degree views of the city of Rome, from the Villa Lodovisi on the Pincian Hill, and from the Capitol.

A 'Roman Bath'

Image: The Strand Lane ‘Roman’ bath in 1841

Image: The Strand Lane ‘Roman’ bath in 1841

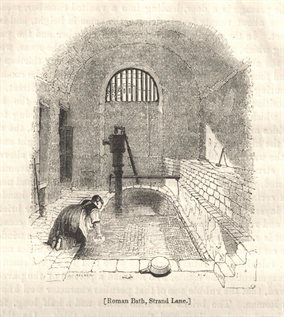

A hundred metres or so south of 169-171, just off Surrey Street and also within the Strand Campus perimeter, stands the so-called 'Roman Bath', now managed by Westminster Council on behalf of the National Trust.

It is clear now that the 'Roman Bath' is not genuinely Roman, but dates to the seventeenth century. However it was passionately believed to be ancient, and was advertised as a bathing-place on these grounds from the 1830s into the middle of the 20th century.

Arundel & Somerset

Strand Lane, on which the 'Roman Bath' stands, was once the boundary line between two noble palaces of the renaissance and early modern periods, Old Somerset House to the west and Arundel House to the east.

The 'Roman Bath' on the east side of the lane was originally the cistern building to a royal fountain in the grounds of Old Somerset House, showing Mount Helicon with Pegasus and the Muses. Arundel House is celebrated as the first place in the country where a collection of ancient sculpture and stonework was placed on semi-public display – what now survives in part in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, as the Arundel Marbles.

Reanimating the ancient world

Image: a Roman fantasy of the Strand Lane bath, 1922

Image: a Roman fantasy of the Strand Lane bath, 1922

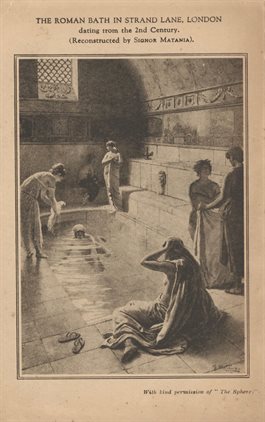

The themes of sculpture and ancient stonework link the 'Roman Bath' and Arundel House to the Elgin Marbles' period of residence in the Aldwych tube tunnels, and to the Royal Strand’s plays about statues coming to life; all of this backgrounds our strength in the study of ancient art, and its interactions with the modern world.

At the same time, the desire to believe in the 'Roman Bath' as a genuine ancient survival, connecting modern bathers with Roman Londoners of the time of Vespasian, chimes with the other ways in which the ancient world has been dreamed of and recreated in imagination in the area, successively in the Panorama and the Royal Strand Theatre (not to mention the printing and publishing houses with which the Strand used to be lined).

The fact that all of this has taken place in the same angle of Surrey Street and the Strand as is occupied now by the Department of Classics at King's makes our current home a peculiarly appropriate one.

The Beginnings: Professor Anstice’s Inaugural Lecture

Image: The memorial inscription to Joseph Anstice in St Michael's Church, Enmore

Image: The memorial inscription to Joseph Anstice in St Michael's Church, Enmore

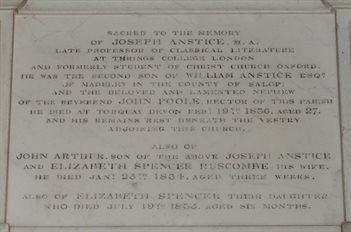

If the Department of Classics has a foundation document, it is the Introductory Lecture delivered by the College's first Professor of Classical Literature, Joseph Anstice, on 17 October 1831.

Surveying each branch of Classical learning as it was then constituted – history, science, philosophy, poetry, and philology – Professor Anstice assesses "the advantages to be derived from the study of the authors and languages of Greece and Rome."

Anstice was appointed very young, at the age of 22, fresh from his university degree at Christ Church Oxford, but had to retire only four years later through ill health. He died at the tragically young age of 28, in 1836. He is commemorated in King’s by a handsome marble inscription now located over the door of the Dean's Office, but originally placed in the College Chapel, and another at the church in Somerset (St Michael’s, Enmore), where he is buried.

Since Professor Anstice's day the scope of classical teaching at King's has expanded far beyond just Greek and Latin language and literature, to include Greek, Roman and Near Eastern history, Greek and Roman archaeology and art, Byzantine and Modern Greek studies, and the reception of the ancient world.

The Tale of Troy: a history of the King's Greek Play

Today’s annual King’s Greek Play continues a long history of the performance of classical drama at King’s. One of our most colourful contributions to the popularization of Classics took place in late May and early June 1883, when four performances – two in English, two in Greek – were given of an adaptation of the Iliad and the Odyssey entitled The Tale of Troy. This combination of tableaux vivants, dialogue scenes and songs was the brainchild of the then Professor of Classical Literature at King's, GCW Warr, and was designed to raise money to buy and adapt a premises in Kensington for the newly founded King's College Lectures for Ladies.

Today’s annual King’s Greek Play continues a long history of the performance of classical drama at King’s. One of our most colourful contributions to the popularization of Classics took place in late May and early June 1883, when four performances – two in English, two in Greek – were given of an adaptation of the Iliad and the Odyssey entitled The Tale of Troy. This combination of tableaux vivants, dialogue scenes and songs was the brainchild of the then Professor of Classical Literature at King's, GCW Warr, and was designed to raise money to buy and adapt a premises in Kensington for the newly founded King's College Lectures for Ladies.

Though originally planned on a fairly modest scale, it grew in the process of preparation, and when eventually performed – in the South Kensington mansion of Sir Charles Freake – it had been transformed into a lavish spectacle and a major social event, bringing together many of the then leading lights of the worlds of scholarship, art, music, the stage and high society. You can download a transcript of The Times reviews of the 1883 production, and of Warr’s own account, written years later for the King’s College Ladies Department magazine.

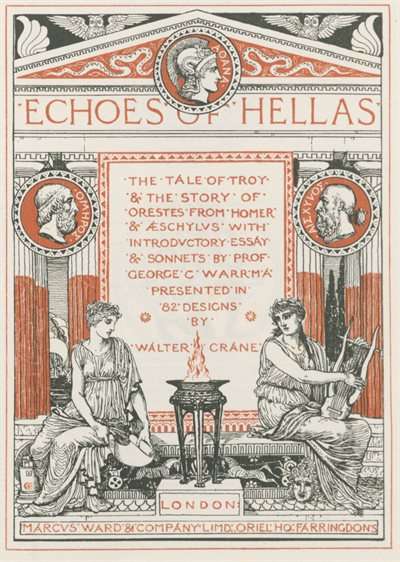

Three years later, in May 1886, the production was revived in an expanded version that also included the story of Orestes, adapted from Aeschylus's Oresteian Trilogy. This time the performances, at Prince's Hall in Piccadilly, and given in the presence of the Prince and Princess of Wales, were in aid of a fund for the extension of University teaching in London.

In 1887, the complete text of the final version, along with the music, was published as Echoes of Hellas (London: Marcus Ward, 1887), with illustrations by Walter Crane, based in part on the original stage designs.

The fact that the 1883 production was in aid of university lectures for women is no accident. Its mastermind, George Warr, was an active supporter of socially progressive causes of many kinds – social purity, free trade, Irish independence and the foundation of a National Theatre, as well as higher education for women. King’s Classics follows his example in our commitment to Widening Participation, and making ancient world studies accessible to all through endeavours such as Advocating Classics Education and The Iris Project.