Given the lack of a jaw joint in marsupials and monotremes at birth, scientists have previously suggested that the animals may use a connection between the middle ear bones and jaw bones to allow them to feed.

Neal Anthwal, Research Associate at the Centre for Craniofacial & Regenerative Biology

30 June 2020

Hints at jaw evolution found in marsupials and monotremes

A connection between ear and jaw bones in marsupials and monotremes shortly after birth provides hints at the evolution of these bones in early mammals.

Infant marsupials and monotremes use a connection between their ear and jaw bones shortly after birth to enable them to drink their mothers’ milk, new findings in eLife reveal.

This discovery by researchers at King’s College London, UK, provides new insights about early development in mammals, and may help scientists better understand how the bones of the middle ear and jaw evolved in mammals and their predecessors.

Marsupials such as opossums, and monotremes such as echidnas, are unusual types of mammals. Both types of animal are born at a very early stage in development, before many bones in the body have started to form. Opossums latch on to their mother’s nipple and stay there while they finish developing. Monotremes, which hatch from eggs, lap milk collected near their mother’s milk glands as they grow. But how they are able to drink the milk before their jaw joint is fully developed was previously unclear.

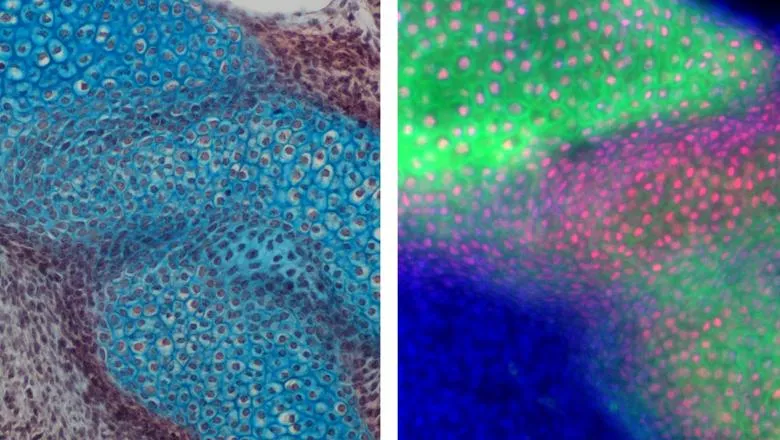

To find out if this is true, Anthwal and his colleagues compared the jaw bones in platypus, short-beaked echidnas, opossums and mice shortly after birth. Their work revealed that, soon after echidnas hatch, their middle ear bones and upper jaw fuse, eventually forming a joint that is similar to the jaws of mammal-like reptile fossils. The team found a similar connection in mouse embryos, but this disappears and the animals are born with functioning jaw joints.

Opossums, by contrast, use connective tissue between their middle ear bones and the base of their skull to create a temporary jaw joint that enables them to nurse shortly after birth. “This all shows that marsupials and monotremes have different strategies for coping with early birth,” Anthwal says.

The findings suggest that the connection between the ear and jaw dates back to an early mammal ancestor and persisted when mammals split into subgroups. Marsupials and monotremes continue to use these connections temporarily in early life. In other mammals, such as mice, these connections occur briefly as they develop in the womb but are replaced by a working jaw joint before birth.

Our work provides novel insight into the evolution of mammals. In particular we highlight how structures can change function over evolutionary time but also during development, with the ear bones moving from feeding to hearing. The recent availability of monotreme tissue for molecular analysis, as showcased here, provides an amazing future opportunity to understand the biology of these weird and wonderful mammals, which we are keen to explore.

Abigail Tucker, Principal Investigator and Professor of Development & Evolution

Reference

The paper ‘Transient role of the middle ear as a lower jaw support across mammals’ can be freely accessed online at https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.57860. Contents, including text, figures and data, are free to reuse under a CC BY 4.0 license.