18 November 2019

A better system for parental leave

Emilie Gachon and Emilie Steinmark

EMILIE GACHON AND EMILIE STEINMARK: Parental leave in the UK is amongst the least generous in the OECD, a complete overhaul would benefit families and help rectify gender inequality.

This piece is part of a blog series from the student finalists of Policy Idol 2019. Through the series, we're sharing students' policy ideas for changing the world, which they pitched at the competition earlier this year.

Find out more about Policy Idol

Parental leave in the UK is old-fashioned and disproportionate. The amount of benefit parents receive is amongst the lowest in the OECD, and lower-income parents have even further unequal access to paid leave. A complete overhaul is desperately needed.

Currently mothers are only entitled to six weeks leave at 90 per cent of pay. The remaining weeks are either compensated well below the living wage at £145 a week for 33 weeks or not at all for 13 weeks. Fathers have it even worse, being entitled to only two weeks at £145. An attempt was made to modernise the system in 2015 with the introduction of Shared Statutory Parental Pay, which gave parents 37 weeks to share between them, but due to the meagre amount received, it doesn’t make financial sense to many families. Uptake is estimated to be as low as two per cent.

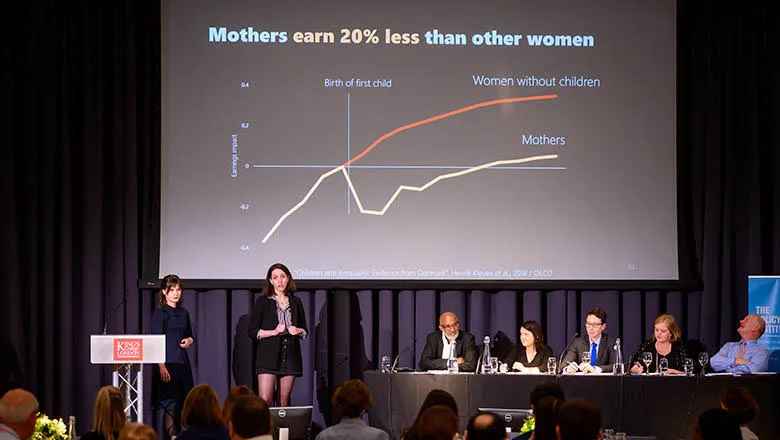

As it is only mothers who receive properly paid leave, so they end up being the parent responsible for most of the child-rearing in the family, not only in the first year but throughout parenthood. Consequently, women face an average drop of 20 per cent in long-term earnings when they become parents, whilst it doesn’t really affect men. And it gets worse the more children you have – with a 10 per cent cut to a mother’s salary every time she has a child. This is a main contributor to the gender pay gap which in the UK is still at 19 per cent.

We suggest a new parental leave system that gives families real choice over how to raise their children. It would be financially beneficial for both parents and society. It would provide parents with four months of use-it-or-lose-it leave at 90 per cent pay each, plus an additional four months to share between them.

The first beneficiaries would be the children. By extending the time that parents can afford to go on leave, it gives mothers and fathers the choice to stay home longer with their children. This is important for health reasons, as mothers could then breastfeed for the recommended six months, but it also comes with educational benefits, as research has shown that giving fathers longer leave results in children performing better in cognitive tests and then later, in improved school performance.

This policy would be a game-changer for fathers. The choice to spend time with your baby, investing in your family should not just be reserved for the most well-off. There is evidence to suggest longer paternity leave could help to prevent family breakdowns – Swedish couples are 30 per cent less likely to separate if the father takes leave, if they do separate, fathers stay more involved with their children.

Finally, this policy is financially viable for families and tackles the gender pay gap. Per month of leave that fathers take, Swedish data suggests that mothers’ long-term earnings increase by 6.7 per cent, combatting the baby penalty. Danish evidence shows that this contributes to an overall increase in household income. On top of this, there are upfront savings of £6,000-8,000 in childcare costs.

This policy would benefit society as a whole – a 2012 OECD report found that if UK women returned to work at the same rate as men, GDP could rise 10 per cent by 2030. Former Managing Director and Chairwoman of the IMF, Christine Lagarde, echoed this during a recent statement when she shared that helping women return to work after becoming mothers could boost the economy. Long paternity leave could lead to more equal child-rearing, helping to make this a reality for mothers.

Naturally, this policy will require some initial investment. If British fathers took their paternity leave at the same rate as Swedish fathers (just under 30 per cent) this policy would cost £3.8 billion (assuming everyone is eligible). However, evidence suggests the uptake would be gradual and the actual figure is likely to be much lower.

There are a range of options for financing this system – both Labour and the Liberal Democrats in the past have suggested changes to the income tax system, or corporation tax, and either of which would more than cover the costs.

Importantly, as women start returning to work in higher numbers and parents can share child-rearing responsibilities, the bill would shrink as the extra tax revenue begins to compensate.

We think this would be a great opportunity for the UK to lead the way on modern, fit-for-purpose family policy, not just in Europe but globally. The evidence is there, it’s time we followed it.

Emilie Gachon and Emilie Steinmark are PhD students in Physics.