17 July 2020

A classic nudge fails when it comes to Covid-19

Michael Sanders and Emma Stockdale

MICHAEL SANDERS and EMMA STOCKDALE: Loss aversion messages did not make people more cautious

Much has been made of the use of behavioural science by government during the pandemic. Although the fundamental problem faced is a medical and epidemiological one, the behaviour of individual human beings, and the extent to which they comply with the guidance, is a behavioural one. This is reflected in the existence of SPI-B, a group of behavioural scientists advising the government’s Scientific Advisory Group on Emergencies (SAGE).

This makes a lot of sense, as we have argued elsewhere: if the main vector for transmission of the virus is human beings, understanding the way that they behave – their psychology – can be as crucial as understanding the way that the virus itself behaves.

A pressing challenge is that even the most robust findings in social psychology were produced under what we can only call “normal circumstances” – ie not in the middle of a global pandemic. The heightened emotional environment that we are all growing accustomed to over the last few months or so put us in uncharted territory psychologically. In a recent experiment, we tested whether this made a difference to our ability to learn from psychological studies.

To do this, we built on research on loss aversion but in the context of coronavirus. It is one of the most robust findings in social psychology that people value losses more – about twice as much – as they do gains of equivalent size. This desire to avoid losses makes us behave in some interesting ways, paying more, and taking more gambles, to avoid a loss than we would to achieve a gain of the same size.

This was originally tested by Nobel Prize winners Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky (1981), using the example of the “Asian disease”, a hypothetical scenario in which people need to choose between two different policy prescriptions – one risky and one less risky – either framed in terms of the number of lives that could be saved, or the number of lives that could be lost.

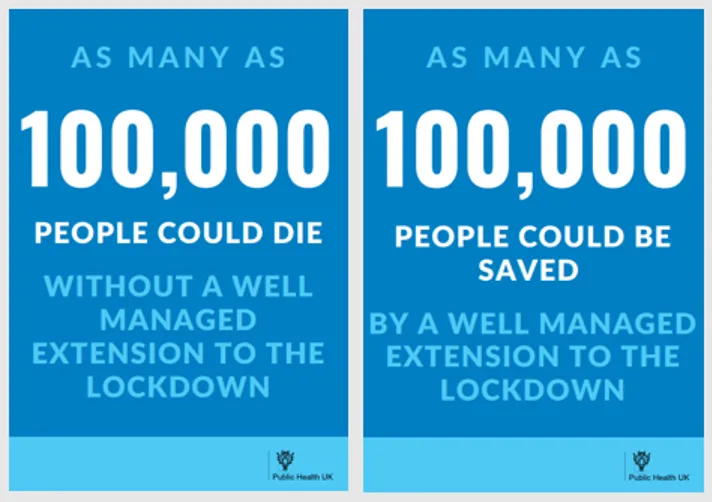

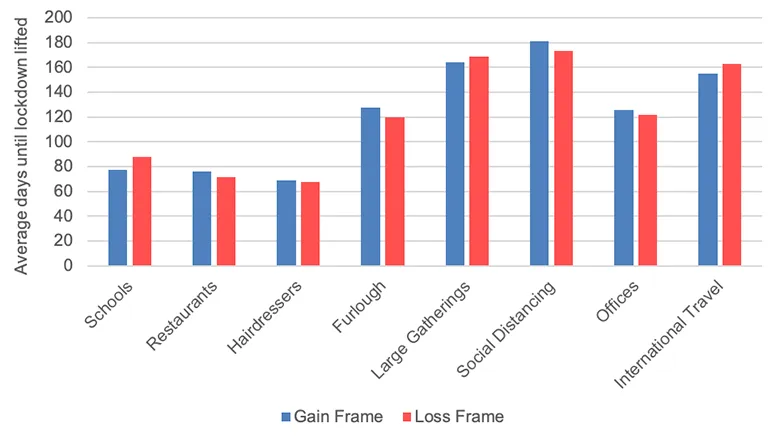

We updated the example to use figures from current modelling of likely coronavirus deaths (Figure 1), and asked people to tell us how long they felt the lockdown should last, and when they thought particular types of businesses should open.

What we found surprised us. There was no effect of these loss aversion messages at all, and in some of our outcome measures, the effects actually went in the opposite direction to what we predicted.

The fact that we failed to replicate such a core study from behavioural science in a coronavirus context suggests to us that the heightened emotional state of the pandemic, and our acute awareness of the losses involved, might have dampened the impact of some of the most powerful “nudge”-type interventions, and hence that we need maintain an empirical mindset. In other words, in behavioural science as in medical science, testing is key in defeating the virus.

Dr Michael Sanders is a Reader in Public Policy at the Policy Institute, King's College London, and Chief Executive of What Works for Children’s Social Care.

Emma Stockdale is a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Economy at King's College London.