Making Domesday offers our interpretation of a collaborative investigation which has proved an utter education. We have learned so much not just about the Domesday process itself, but about the people responsible for writing it, the quite extraordinary way they collaborated, and, if my own projections are correct, about their diverse origins outside as well as within the Anglo-Norman realm.’

Professor Julia Crick

02 July 2025

Author of William the Conqueror's 'Medieval Big Data' project revealed

A landmark study has shed new light on the Domesday survey of 1086 - one of the most famous records in English history - revealing it as an audacious and sophisticated operation of statecraft and data management.

The findings, presented in Making Domesday: Intelligent Power in Conquered England (Oxford University Press, 2025), challenge long-held assumptions about the scale and intent of William the Conqueror’s great survey.

Drawing on the earliest surviving manuscript of the survey, known as Exon Domesday, researchers argue that the survey was not simply a means of maximising tax but a far more ambitious and intricate exercise in governmental control - akin to an 11th-century form of big data processing.

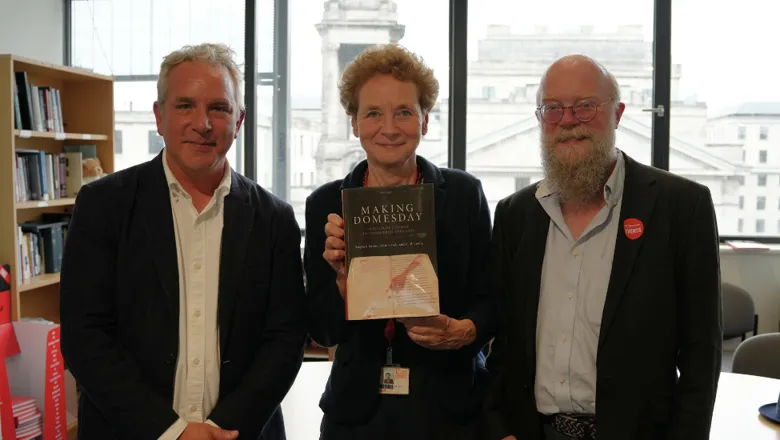

Professor of Palaeography and Manuscript Studies, King's Julia Crick, Professor Stephen Baxter (University of Oxford), and Dr C. P. Lewis (Institute of Historical Research, University of London) have uncovered how William’s administration gathered vast quantities of economic and territorial data across England in under seven months. The information was recorded, reorganised, and redeployed with astonishing speed and clarity of purpose.

Professor Crick highlights the diversity of where the scribes were found to have travelled from.

Professor Stephen Baxter said: 'One of the points that emerges forcefully from this study is just how clever Domesday’s creators were. Their survey exudes intelligence. It was carefully planned, drawing on ancient precedents for taking large-scale surveys, and made rational use of existing systems of government; but it was also implemented with breathtaking efficiency and was conceptually innovative, foreshadowing the profitable exploitation of big data in the modern world, using technologies no more complex than pen, parchment and human interaction. Domesday was the product of raw, not artificial intelligence.’

In a discovery likely to reshape scholarly understanding, the team also proposes a likely identity for the principal scribe of Domesday Book - known until now only by his distinctive handwriting. Their research suggests he was Gerard, William’s final chancellor, later Bishop of Hereford and Archbishop of York. If confirmed, this would make Gerard one of the few named individuals directly linked to the great survey and the production of Domesday Book.

The study draws on the rich evidence of Exon Domesday - a manuscript compiled in 1086 by a team of scribes working under intense pressure, and the earliest surviving record of the survey. The team applied modern forensic and analytical techniques to unlock new insights into how the manuscript was created and used.

The authors worked on their project 'Exon: The Domesday Survey of South-West England' which started at King's in 2014 (concluding in 2017) and was a collaboration between scholars from King's College London, the University of Oxford and the Friends and Dean and Chapter of Exeter Cathedral.

Dr Chris Lewis said: ‘Engaging with how Exon Domesday was written was exhilarating. At times I felt I was sitting with the team of scribes in Winchester over the ten weeks they were at work in the early summer of 1086. Understanding Exon helped us to reconstruct how the Domesday survey was conducted and how Domesday Book was written. It also gave a glimpse of the humanity of those anonymous scribes: how they worked as a team, and how each had his own habits and oddities, with strange spellings, blunders and corrections, and doodles which include musical notation and a biblical reference to wine. Working on a collaborative research project about a collaboratively written text was full of rewards.’

By offering a new interpretation of how, why, and by whom Domesday Book was made, Making Domesday repositions the record as not only a cornerstone of medieval English history but a remarkable feat of administrative innovation.