07 April 2020

Blog: The ten most dangerous coronavirus myths debunked

Let's look at some pictures of real data.

In this blog, originally published on Inspire the Mind on 25 March 2020, Anna McLaughlin, Clinical Neuroscience PhD student at King's College London, explores and debunks the current myths around COVID-19.

The coronavirus pandemic has swept across the globe at breakneck speed, bringing whole countries to their knees in a matter of weeks. In tandem with the virus, we have been inundated with a daily torrent of news updates, scientific discoveries and rapidly changing government policies.

We have also been inundated with conflicting ‘facts’ about coronavirus, ranging from misquoted statistics, to rather convincing pseudo-science and downright laughable conspiracy theories. This quickly becomes overwhelming for everyone and soon it’s hard to remember which advice came from a meme and which advice came from the World Health Organisation.

Unsurprisingly, for most of us this uncertainty leads to poor mental health, increased stress and further confusion about how to approach the problem, along with a mistrust of the sources who deliver information to us.

This is why we have collected and debunked the top 10 most dangerous myths about the coronavirus disease pandemic (COVID-19), using the best charts and illustrations from around the web to visually guide you. This is the start of a new series of myth-debunking blogs from Inspire the Mind, so as more myths are inevitably created, keep an eye out for more articles like this in future.

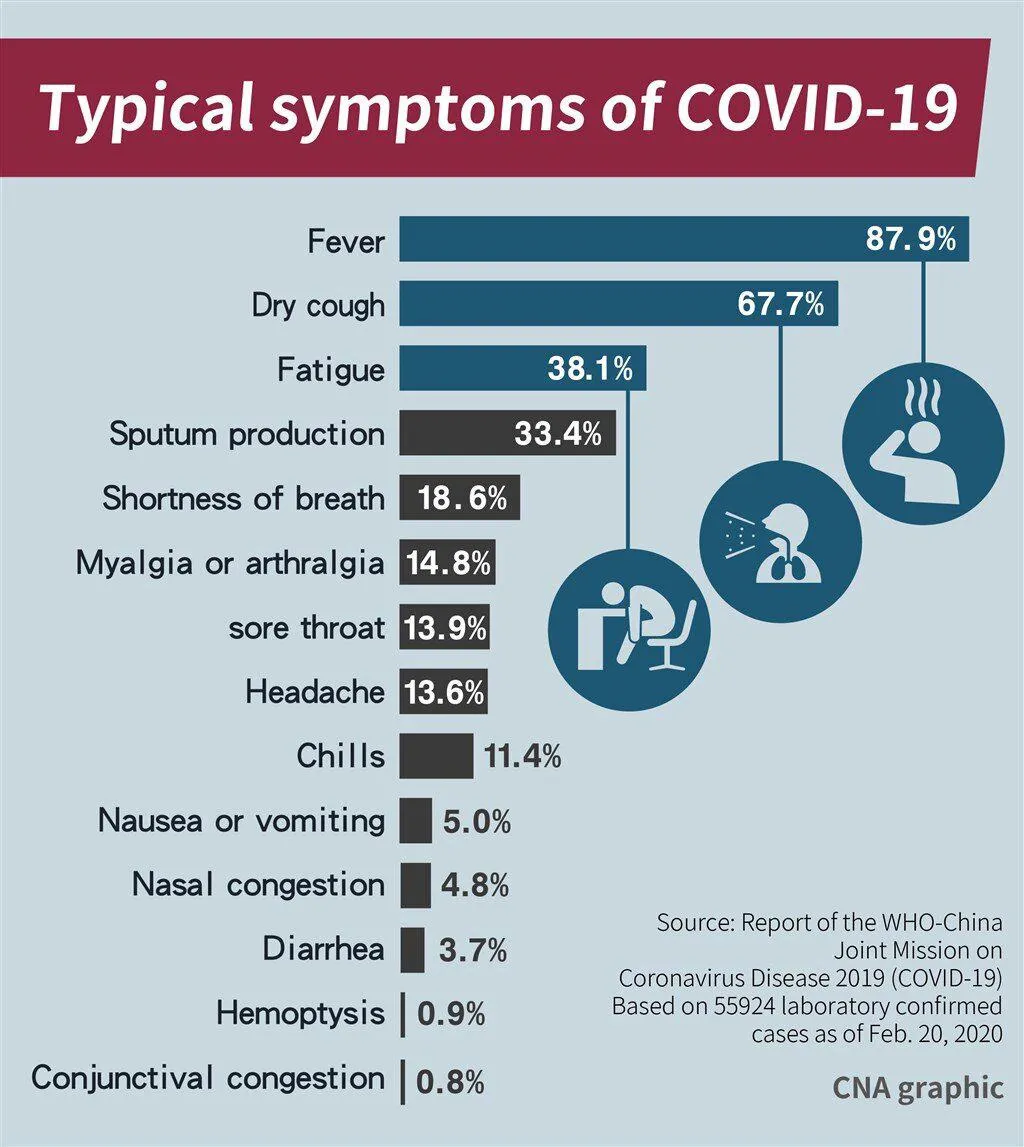

Myth 1: I don’t have a cough or fever, so I don’t have the virus

Symptoms are varied and not limited to coughs and fevers.

The confusion around this likely came from coughs and fevers being the most common symptoms, but less common symptoms include myalgia (muscle pain), nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea. What is most surprising, is that a large number of patients may also lose their sense of smell and taste. This can occur in the absence of any other symptoms, meaning this discovery could be key in identifying very mild cases of coronavirus that would not otherwise be identified, according to the medical body ENT UK.

The most typical symptoms are shown here:

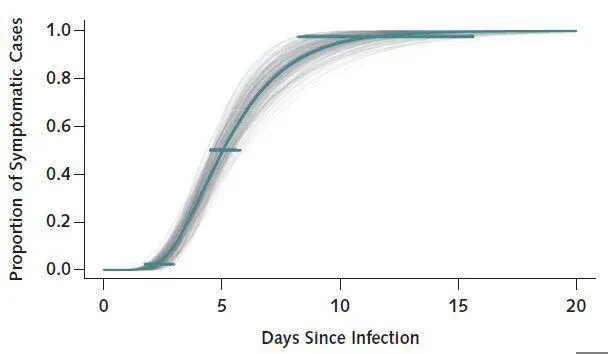

Myth 2: I don’t have any symptoms, so I don’t have the virus

Most people who get sick from the virus will only show symptoms approximately 5 days after being infected, but it can take up to 15 days in some cases.

One study found that during those initial 5 days (where people feel completely fine), is when the highest amount of viral shedding likely occurs, which is when infectious particles from the virus spread from one person to another. Young children might not be as vulnerable to the virus, but they may be an important source of transmission, as a study published in Nature Medicine and another study in China both found that children without symptoms were still highly infectious.

In reality, we do not know how many people might be completely asymptomatic (meaning, without symptoms) while carrying the virus. Early research of Japanese evacuees from Wuhan suggests that about 30% of infected people may have no symptoms at all. Another study of German evacuees found that screening for the virus based on symptoms was ineffective, because even asymptomatic patients were infectious.

This is why it’s so important to isolate yourself for at least 14 days, if there’s any possibility that you might have been exposed, and why social distancing is essential for everyone (see myth #8 for more info).

It usually takes 5 days to start showing symptoms, but in some cases may take 10–15 days:

Myth 3: Coronavirus is just like the flu

This myth was used to downplay the danger of the virus when it was first beginning to spread from Wuhan to Europe, along with rumours about the danger of the virus being blown out of proportion. It’s now very easy to say, without a doubt, that:

1. Coronavirus is far more deadly than the flu, not just for older people, but for all people.

2. Coronavirus has a much higher hospitalisation rate compared with the flu (19% vs. 2%).

3. The duration of hospitalisation for coronavirus is approximately 10 days longer than the flu.

4. Transmission rates of coronavirus (how quickly the infection spreads) are much higher than the flu.

5. The flu has been around for over 100 years, so we built up an immunity to it. Despite this, thousands of people require flu vaccines every year because the influenza virus continuously mutates. In contrast, humans have no immunity to coronavirus, because it is a brand-new type of virus, making the whole population far more vulnerable.

6. We don’t have any known treatments or a vaccine for coronavirus yet.

7. Due to all of the above, the risk that coronavirus poses to humans is far greater than the common flu.

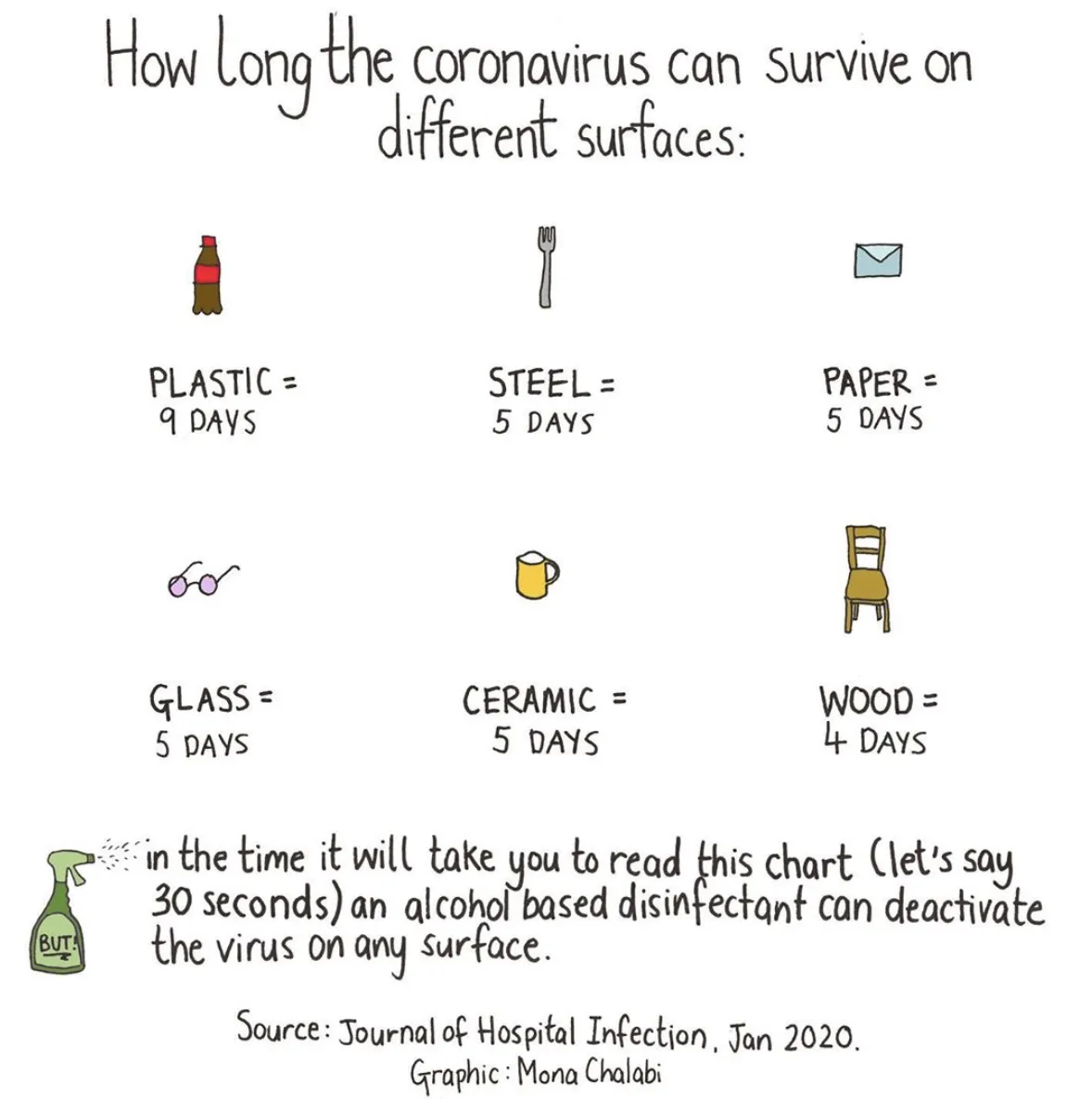

Myth 4: I can only catch coronavirus directly from infected people

Unfortunately, coronavirus can live easily on a range of surfaces for several days.

One peer-reviewed study found it could last on some surfaces, like plastic, for up to 9 days. However, the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention discovered that the virus survived on surfaces for 17 days, after infected passengers disembarked from a cruise ship.

This is why disinfecting surfaces and washing your hands regularly is so important.

Luckily, a simple alcohol-based disinfectant is enough to deactivate the virus.

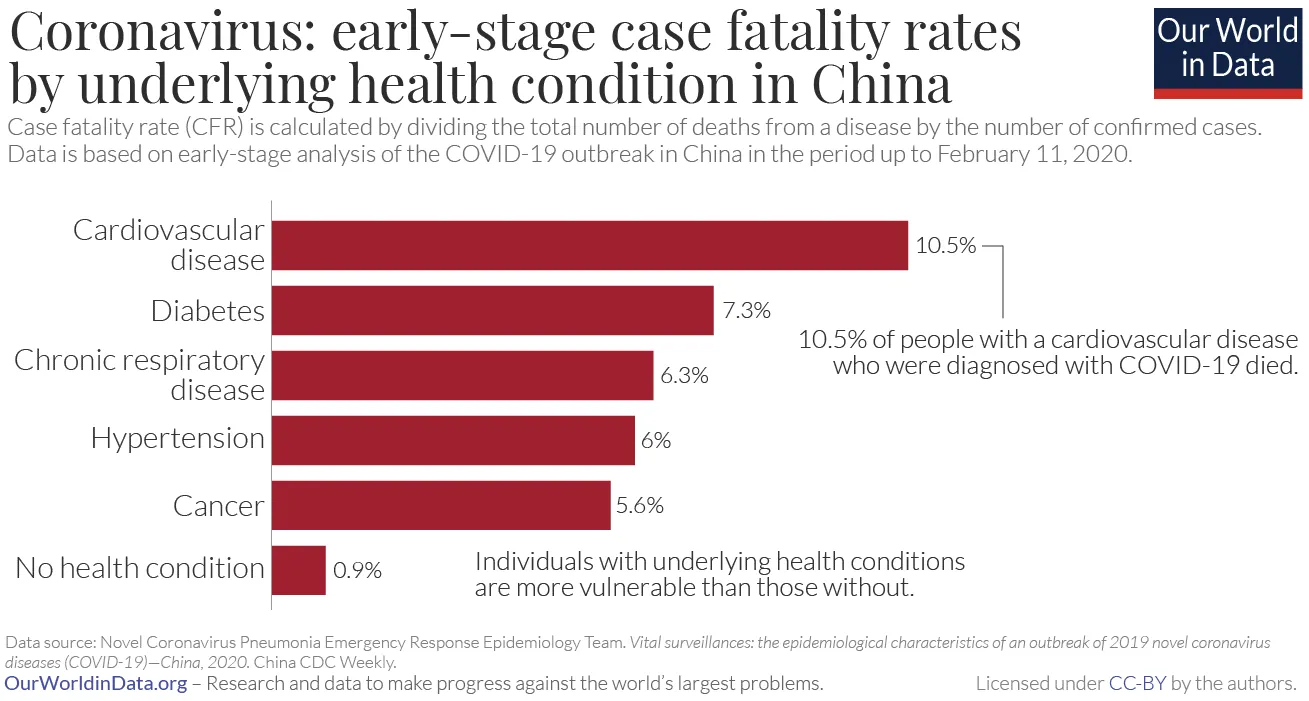

Myth 5: I’m young and have no health problems, so I’m not at risk

Although being young and not having any underlying health problems means you do have a lower risk, young and healthy people are still very much vulnerable to the virus.

A review of over 500 US patients found that 20% of those aged 20 to 44 were hospitalised due to serious complications and 20% of deaths occurred in those aged between 20 to 64 years.

Pneumonia is one of the most common causes for hospitalisation in patients with coronavirus. Between 15–20 days of mechanical ventilation is typically required to assist breathing for those recovering from pneumonia. This means younger generations should seriously consider that simply contracting coronavirus could put a huge strain on an already overburdened healthcare system.

Furthermore, the risk of death is not simply down to older age.

Anyone with an underlying health condition is at an increased risk of death, even those with common conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic asthma and hypertension. Risk is also far higher those with weakened immune systems, including people with autoimmune diseases and cancer patients.

It is impossible to be aware of all the health conditions of each person you interact with, so anyone who knowingly puts themselves at risk of contracting and passing on the virus is seriously jeopardising other people’s lives.

Consider that one of the youngest coronavirus deaths was a 21 year old male football coach , Francisco Garcia, who unexpectedly went to hospital for breathing difficulties. At hospital, he was diagnosed with pneumonia (caused by coronavirus), as well as leukaemia. Prior to his hospital trip, Francisco was completely unaware he had either disease. Within one hour he went from being in a stable condition to being pronounced dead. Francisco never even had an opportunity to receive potentially life-saving cancer treatment for his leukaemia.

Myth 6: Wearing a mask will stop me from catching it

With this myth it’s easy to see where the misunderstanding has come from.

While masks are most helpful in preventing infected people from spreading the virus (by stopping viral particles from sneezing and coughing being released), they are not as effective in preventing the general public from catching the virus, especially if people are already practicing social distancing when traveling on public transport or walking around.

In fact, intermittently putting a mask on and taking it off actually increases the amount of times you touch your face, which could increase the likelihood of putting infectious particles around your mouth, nose and eyes.

While masks are in short supply, they should be predominantly reserved for healthcare workers and carers, who work in very close proximity with large numbers of infected patients.

For the general public, more effective methods of protecting yourself from infection include regularly washing your hands, not touching your face, disinfecting surfaces, and social distancing.

If you already have a mask then there is no harm in wearing it, but make sure your mask is sanitised and that your hands are clean when taking it off and putting it on. And wash your hands again after taking it off.

Myth 7: It would be better to let everyone catch the virus so that we become immune to it, even if it causes some deaths in the short-term

Although this strategy (known as herd immunity) is not something that many people might admit to thinking, it is naturally on people’s minds when the current alternative we are facing includes widespread job losses, school closures, economic recession, and being confined in our own homes for an indefinite period of time.

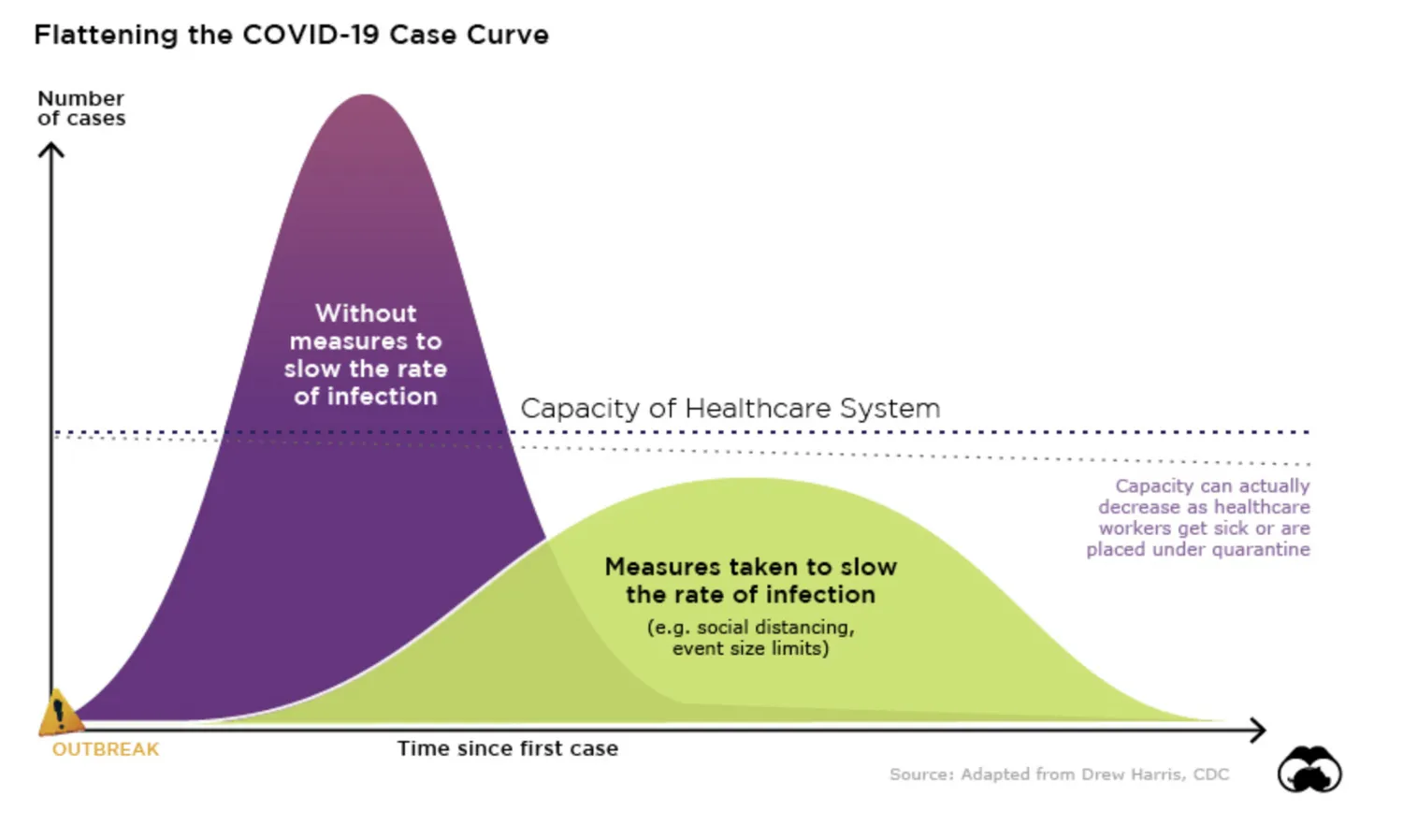

To put things in perspective, if everyone caught the virus without any strategies in place to suppress it, this would lead to an enormous number of deaths, a devastated healthcare system and subsequent irreparable breakdown of society and the economy. A team of scientists at Imperial College London modelled what this would look like in the UK and predicted that it could lead to a quarter of a million deaths that would completely overwhelm the healthcare system for months.

In fact, all sectors would become overwhelmed if a large proportion of the workforce suddenly became ill around the same time (including the doctors and nurses who are meant to treat patients).

It would also prevent people from accessing healthcare, emergency services and even prescriptions for normal medical reasons, and people could begin dying from minor conditions such as asthma attacks, heart attacks, pregnancy complications, everyday accidents, bacterial infections and so on.

Instead of this scenario, governments are aiming to eventually achieve widespread immunity with vaccination, when one becomes available. This way a large part of the population will become immunised in a controlled manner, drastically minimising the devastating potential of the virus.

Flattening the curve using social distancing:

Myth 8: Social distancing should only apply to people who might be infected

Unfortunately, we cannot distinguish who is infected and who is not, because of the amount of time it takes infected people to develop symptoms and the large number of infected people without any symptoms at all (see myth #2).

One study of Wuhan patients estimated that undocumented cases (undiagnosed) were responsible for infecting 79% of documented cases, explaining the rapid spread of the virus.

The transmission rate of the virus is incredibly high, so until we know more about the virus and until testing and tracking infections becomes easier, the most effective method of reducing infection rates is through social distancing (by reducing exposure to other people by 75%). If you don’t think social distancing will have much of an impact, consider that if you happen to be carrying the virus and are unaware, within 30 days you could infect 406 people, and then each of them could go on to infect another 406 people…

If we conservatively estimate that the mortality rate is around 2% and hospitalisation rate is 19%, that means with every month of normal interaction you put 8 people at risk of death and 77 people at risk of hospitalisation.

For those of you who do not see any harm in a quick bite at a restaurant or fitting in a gym class, studies have found that the transmission rates of the virus were 18.7 times higher in closed environments, compared with open-air environments.

Myth 9: Things will get better over the summer when the weather warms up

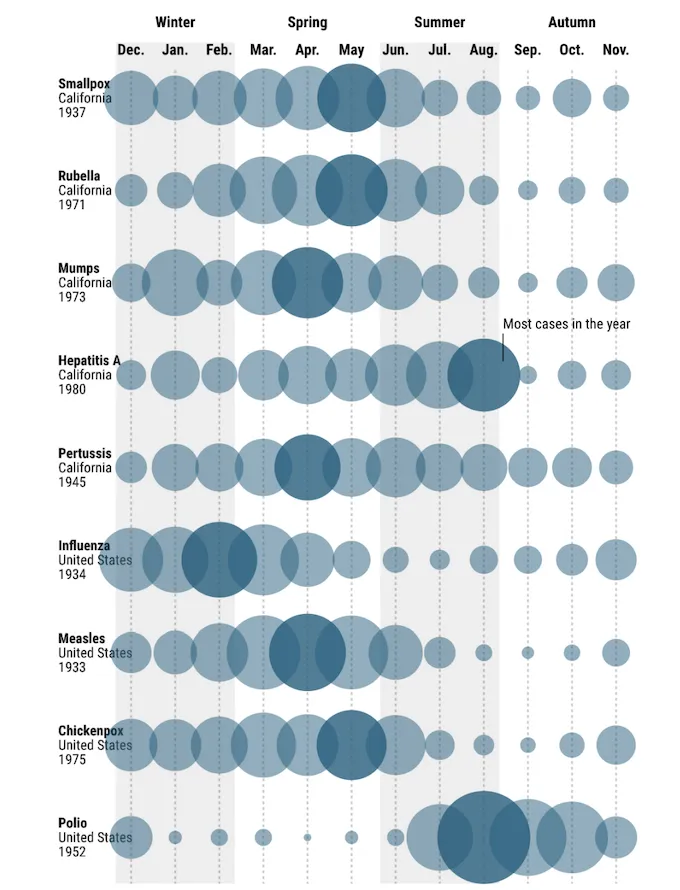

Although this is true for influenza, which declines over summer periods, we don’t know if it will be true for coronavirus yet.

Some diseases vary with seasons while some vary with latitude, some diseases depend on temperature and some largely depend on seasonal human behaviour. Some diseases do not vary seasonally at all.

To further complicate things, coronavirus is a brand-new virus, meaning that humans haven’t built up any immunity to it yet. So even if it is seasonal, the prevalence may continue to increase regardless of seasonality, as it infects more of the population.

The calendar of epidemics:

Myth 10: This will all blow over in a couple of weeks

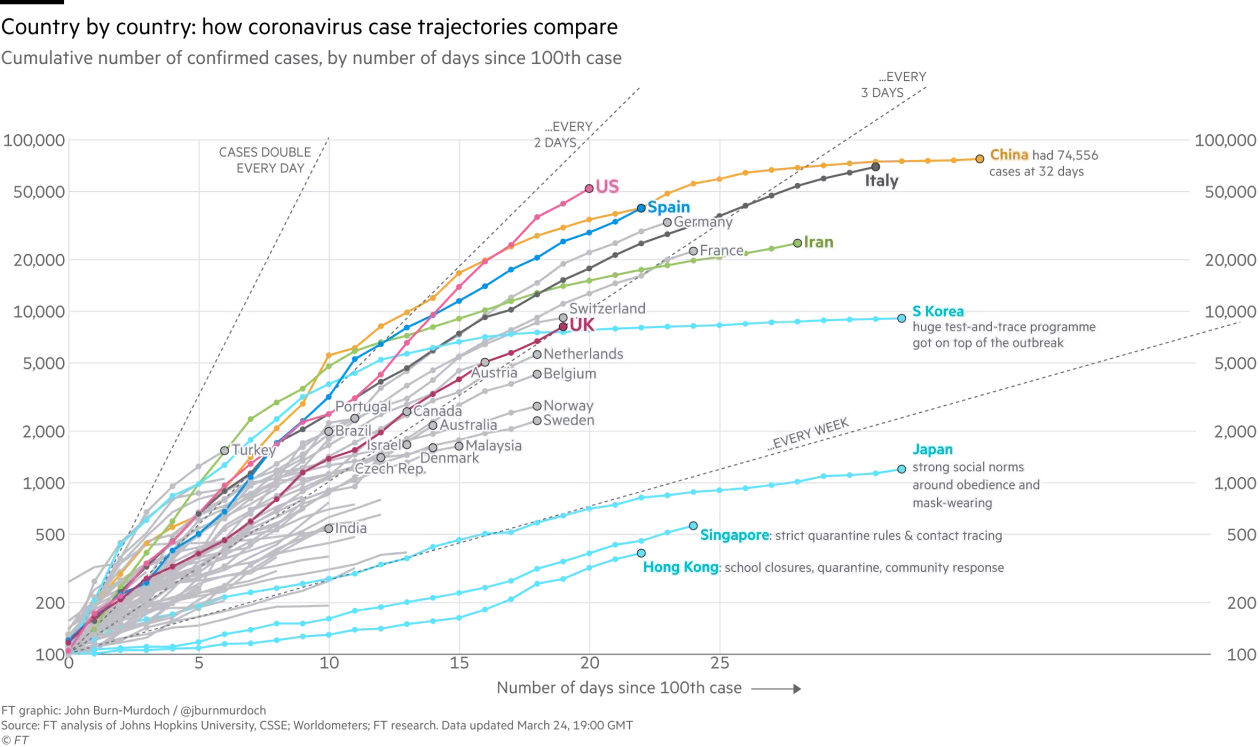

Unfortunately, this is very unlikely because the virus has already been widely transmitted throughout so many different countries.

The most viable option for controlling it now is keeping infection rates low until a vaccine or other treatments are developed.

Without either of these, the best way infection rates can be managed in the coming weeks is through:

· Social distancing (not socialising with people outside of your household and staying home as much as possible).

· Widespread testing to isolate cases.

· Tracking and testing anyone cases have had contact with.

Observing how the situations in China, Singapore, South Korea and Italy develop will give us some indication of what might lay ahead for the rest of the world, but how quickly government policies are implemented and how well citizens respond to those policies will largely dictate if the virus can be contained.

Trajectories of coronavirus cases by country:

For an effective vaccine to be created, and a sufficient proportion of the population to be immunised with it, estimates are currently between 12–18 months at a minimum.

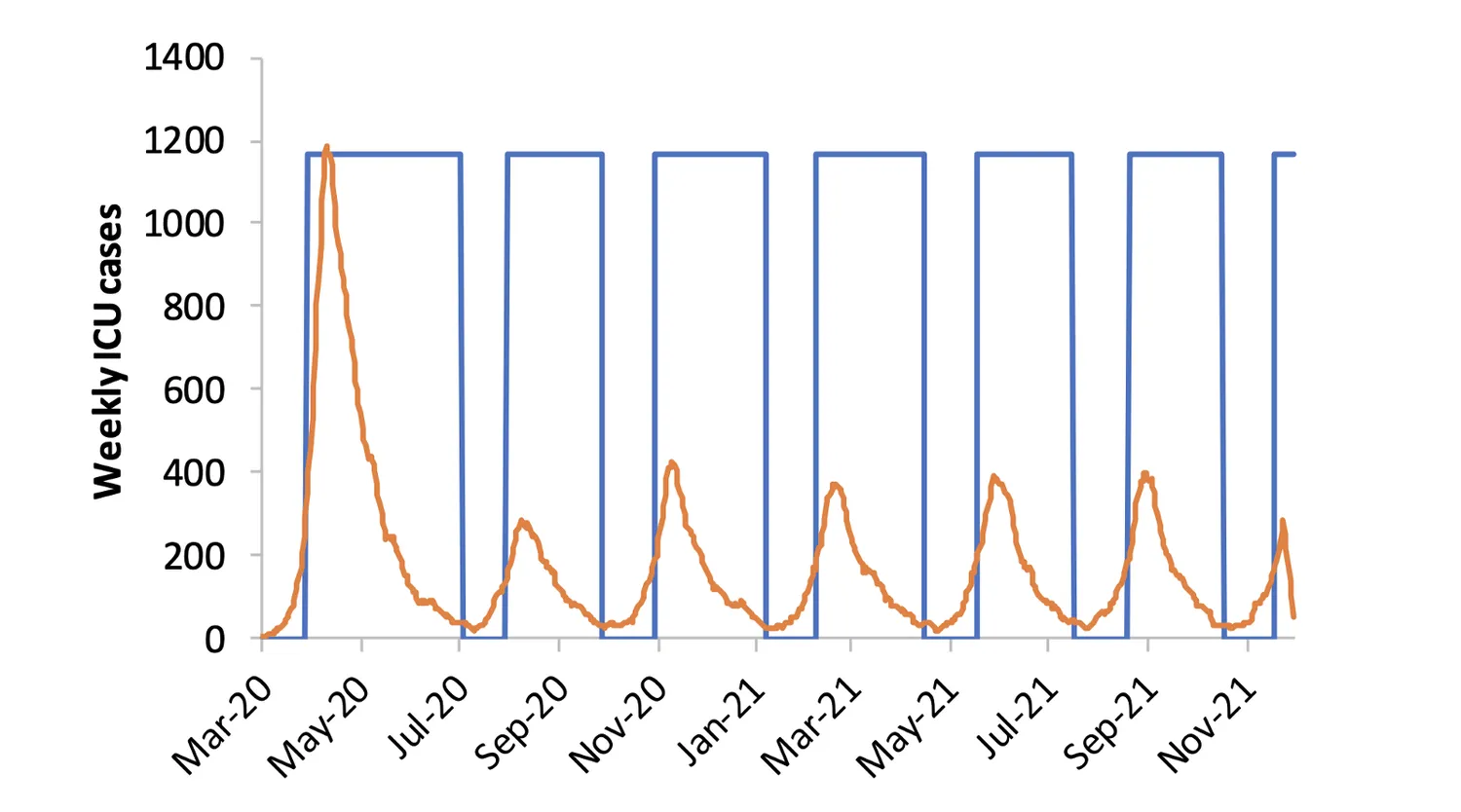

Until then, the suppression model (see below) put forward by the COVID-19 response team at Imperial College London predicts that the best way to keep infection rates at a manageable level will be by interspersing longer periods of social distancing (signified by the straight blue lines) with shorter periods of normal interaction. The time periods of each will need to be adjusted continuously depending on the number of new cases and number of patients in intensive care (orange spikes).

However, if the public can adhere to strict social distancing measures now, this will limit the spread of the virus, ensure cases are isolated and buy more time for the healthcare system to prepare itself.

This would mean that social distancing measures would not need to be as draconian or prolonged after we get through this initial outbreak.

Worst-case scenario of what the next 18 months could look like:

In summary, coronavirus is currently one of the biggest threats many of us will have experienced in our lifetimes.

The only way to keep infection rates at manageable levels for now is through limiting the spread of the virus as much as possible. To successfully implement this globally, each person and each community needs to be aware of how to do so.

Now is not the time to bury your head in the sand, or blindly quote the statistics you saw on Facebook about the virus not being that serious. Nor is it the time to forward scare-mongering chain messages, passed on by a friend of a friend, who claims to be the sister of a doctor, sergeant or Boris Johnson’s dog walker.

Consider that, on Twitter alone, of the 5.9 million tweets related to news stories on coronavirus in the last two months, 1.7 million tweets (one third) were from websites containing unreliable or false information, according to the Bruno Kessler Foundation.

The dangers of passing on false information in a crisis like this can have very profound effects on the physical and mental health of others. For example, following rumours circulated about an enforced London lockdown, hordes of people panicked and emptied supermarkets, leaving elderly people, vulnerable people and even nurses without food.

Humour is a fantastic way to help us cope with an increasingly bleak situation, but when situations like this become life threatening for a large part of the population (which it has) we each have a duty to fact-check and stay updated with reliable sources. Focus on sharing helpful and practical information, rather than sensationalist, clickbait articles.

If you can’t verify something, or someone’s credibility, ask yourself whether you would really benefit others by sharing it.

However, do share this blog, as it is edited from a team of researchers and it is based on scientific evidence.

It’s time to accept the gravity of the situation and act in everyone’s interest, rather than personal interest.

Until we can venture out again, try to have fun and connect with loved ones virtually.

Stay safe, but most importantly keep others safe too!

Inspire the Mind is an online blogging community started by the Stress, Psychiatry and Immunology Laboratory (SPI Lab) King's College London, which is led by Professor Carmine Pariante. The blogs hosted on Inspire the Mind aim to use writing and creativity to open up a conversation about wellbeing, to teach and disseminate the science behind mental health and to encourage others to do the same.

If you're interested in writing a blog post, please contact: inspirethemind@kcl.ac.uk