18 November 2024

COMMENT: Privacy and Trust in Tokenised Money, and how I would design a CBDC

Varun Paul, Affiliate Member, Qatar Centre for Global Banking and Finance, and Senior Director, Fireblocks

Former Bank of England head of Fintech and Affiliate Member of the Qatar Centre for Global Banking & Finance, Varun Paul, spoke at Fintech LIVE in London. He discussed the evolution of digital currencies and explored how central banks and private institutions can design Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) that foster trust, financial resilience, and civil rights protection. Read his speech in full here.

Money is about trust

In his famous book about the human species, Yuval Noah Harari describes money as “the most universal and most efficient system of mutual trust ever devised”. “It can bridge almost any cultural gap”, he writes, allowing people who don’t know each other to work together and trust each other to deliver a greater good.

At the heart of money is trust; why else would someone believe that a piece of paper, or parchment or polymer is worth anything? The person receiving a bank note needs to be able to trust that they can pass that note to someone else in the economy and it be worth the same amount to them too. Ultimately, for a bank note, that trust is derived from the central bank that prints them and devises security methods that makes forgery very difficult to execute and very easy to spot. The central bank goes further too, to ensure that the value of that note remains relatively stable, by trying to maintain a low and stable rate of inflation. Having spent 14 years at the UK’s central bank, it is ingrained deep inside me that trust is hard earned and easily lost.

Digital Money is no different

Modern forms of Money are no different in this respect. Regardless of how it appears or how it is used, the money still needs to be trusted. When we use bank to bank payments, like Faster Payments in the UK, we rely on our bank and the settlement system that connects it to the destination bank, to make good on our commitment to pay someone £10. If the bank decided, on occasion, not to complete the transaction, or the settlement system failed, sending £10 via Faster Payments simply wouldn’t mean the same thing - the electronic £10 wouldn’t have quite the same value as the banknote, and people would use it less.

The same is true for card payments, as well as mobile payments like Apple Pay and Google Pay. Card companies spend a huge amount of time and money monitoring in real-time and ensuring that payment instructions on the card network are valid and can be trusted. Without that trust, the whole card system would rapidly lose its value and its appeal.

Trust in value

Because we’re used to using those payment methods, we are comfortable with them, and we mostly understand the risks and benefits. Digital currencies offer a new way forward and purport to offer better ways to transact. But the core principle of trust still applies.

We’ve seen a proliferation of stablecoins over the past few years. Following the growth in adoption of Tether’s USDT and Circle’s USDC, as well as the spectacular failure of Terra/Luna’s UST, we are now seeing fintechs and banks all over the world issuing digital currencies tied to some nominal value, including Société Géneral in Europe and BanColombia in Latin America. These stablecoins borrow their value from the fiat currencies they are tied to. To manage the financial risk of that endeavour, they need to carefully manage their reserves to ensure holders of the stablecoin can trust in the value of the token they are holding. This became very apparent last year. At the very moment that Silicon Valley Bank was going bankrupt in March 2023, there were significant question marks over the status of the reserves backing Circle’s USDC and we saw a small and temporary de-pegging over the weekend from its par value against the US Dollar.

Trust in Data protection

But it is not only trust in the value of the currency that is important with digital money. With a new technology like this, people need to build trust in its operation too. Data privacy is a core part of that, as we learnt from Facebook’s Libra project. When that was first announced in 2019, it brought home the very tangible risk that a stablecoin could give a sophisticated technology company access to spending and financial data on its 2.4 billion users. Given the amount of data they already collect on us, many people are nervous about sharing even more sensitive data with the largest technology companies.

An opportunity for banks

Banks see an opportunity to step in and address the financial risk. After all, they have been creating money for centuries, quite literally. So tokenising commercial bank money feels like quite a natural thing for a bank to do, and a great opportunity to retain their role in the monetary system as demand for digital assets grows. And - financial crises aside - those that are in business can lean on their track record of financial resilience over many decades to build trust.

They also see an opportunity to address the data protection concern. When asked about who we trust with our data, banks do pretty well. As a highly regulated industry, compliance with data regulations is generally a high priority. My personal theory is that we also trust them because we know they are not capable of harnessing and monetising our data in the way that the technology giants are.

Central banks have a duty to the public

The Libra project also woke central bankers up to the very real risk that they might get left behind and fall short in their responsibility to provide a form of money that had the trust and backing of the state.

Just as they have a role to ensure that the value of the currency remains stable, they have a responsibility to ensure that people can always have access to the money they need. A natural extension of that could be that their money and spending is protected from the commercial incentives of private companies. They do not need to issue all of the money in the economy - certainly they are far from that in today’s economies. Rather, they need to issue enough that it is an always accessible alternative, to offer consumers choice. This also enables them to ensure that £10 is worth £10 always and everywhere, preserving the ‘singleness’ or ‘uniformity’ of money.

It may sound strange, but money issued by different entities carries different risks. When you hold and spend money in a bank account, you are entirely reliant on that bank not going bankrupt. The same is true when you spend money in bank notes: they could be worth less in other currencies if the government defaulted on its debts. And they might be worth nothing if the central bank collapsed. In general, because a central bank can print its own money and is backed by the country’s government, it tends to be the lowest risk form of money to hold. Day to day, we don’t tend to think about these risks, but we know that demand for banknotes rises at times of financial uncertainty, as we saw most recently during the covid pandemic.

We have to remember that tokenised money is not an end in itself. It is needed to access the increasing array of digital assets available. In general, it seems likely that CBDCs will co-exist alongside tokenised deposits and stablecoins, each serving a slightly different purpose, offering consumers choice in how they pay, just as they have today.

While central banks and governments might carry lower financial risk, many people around the world worry about the government spying on them. The level of distrust in the government varies by country, but you can hardly blame people for being sceptical when they see how data can sometimes be used by governments, right across the spectrum from China to the US. And also when they see how governments have acted to freeze bank accounts of people supporting particular causes, including in advanced and liberal countries, like Canada.

Countries are exploring CBDCs for different reasons

Examples of CBDCs around the world show how the design choices depend on the relationship between the people and the state, as well as the policy objectives of the government.

|

Caribbean |

Nigeria |

Australia |

|

Financial inclusion for remote islands |

Alternative to cryptocurrencies |

Work with bank-issued stablecoins |

|

Economically viable alternative to cash |

Improve payments efficiency |

Future-proof payments |

|

Bring money into the formal economy |

||

|

China |

India |

Brazil |

|

Alternative to cryptocurrencies |

Alternative to cryptocurrencies |

Support Digital Asset ecosystem |

|

Compete with AliPay / WeChat Pay |

Building on success of UPI |

Building on success of Pix |

|

Monitor spending, including to support economic management |

Designed to be future-proof |

Interoperability and programmability |

In the Caribbean for example, there was clearly a need to improve the distribution of money to remote islands to ensure everyone had access to the money they needed. Nigeria has been battling with a number of economic challenges and wanted to provide an alternative to crypto, to improve payments efficiency and to reduce the amount of money circulating in the informal economy. To achieve that last aim, they also enforced a redenomination of banknotes, and we got to see what happens when you undermine trust in money. The combination of policies pulled at the very fabric of society and we saw protests on the streets because people were unable to use their money to buy essential goods.

China and India also want to provide an alternative to crypto, and in China they want to reduce the role of Alipay and WeChat Pay, in a way that aligns with their approach to managing the economy. In India, Australia and Brazil, there are clear attempts to make sure their innovation is future-proof, with Australia requiring interoperability with a developing stablecoin ecosystem. And Brazil is seeking to support and enable the growing digital asset ecosystem, which led them to build on blockchains that could work with the Ethereum ecosystem.

These examples illustrate that there are a number of protections for citizens: governance, including the rule of law and regulation; policy, including societal norms and consumer choice; and technology, which can be used to either attack or protect the rights of citizens. I will focus on the design choices through which blockchains and wallets can protect citizens.

The evolution of blockchains

If we roll back the clock 6 years to 2018, as Bitcoin went through a bull run, people quite rightly pointed out that the blockchain could not replace traditional payment rails, because it could not handle the required throughput, because transaction costs were too high and too volatile, and because institutions would be unwilling to use something so vulnerable to hackers. There were issues with energy consumption too. Some were concerned about the anonymity of blockchains, while financial institutions were concerned that their transactions would be too visible to their competitors.

Blockchains have moved on significantly since then. As blockchains have proliferated, they have tried to differentiate themselves with unique features that address these challenges. Some achieved lower transaction costs and gained traction for payments. Others built on top of the Ethereum blockchain and ecosystem to achieve programmability and composability using smart contracts. Similarly, we have seen computational efficiency using proof of stake, shorter settlement times by reducing block lengths, increased transaction throughput, greater auditability and privacy using zero-knowledge proofs, permissioned zones and layer 2 roll-ups.

Many of the critiques that I had of blockchains, as a regulator in 2018, have now been addressed. In particular, I want to talk about governance and privacy, because I completely understand the reluctance of central banks to leverage public blockchains for critical national infrastructure. But the development of permissioned and composable blockchain ecosystems means that we can have a layered approach that preserves the performance, governance and privacy requirements of the financial system.

Blockchains can deliver privacy and trust

Let’s imagine a central bank, operating a core infrastructure at the heart of the financial system. Because it is designed to serve as a platform for innovation, it is built as a blockchain. And because it is so central to the financial system, it is highly permissioned and strictly governed by the central bank.

This blockchain uses the latest capabilities in zero-knowledge proofs to ensure: transparency between counterparties to a transaction, while preserving privacy from others on the network, and providing visibility to the central bank for monitoring and regulatory purposes. Because it is not designed to do everything, it is built on interoperable technology and standards and designed to deliver cross-chain composability.

In a second layer, Bank A operates a separate blockchain, which includes all of its participants. It is responsible for the operation and governance of this second layer blockchain, subject to the rules set by the central bank. In the same way as before, using the latest innovations in zero-knowledge proofs, it delivers transparency between counterparties, without revealing any details to peers on the network, providing privacy. It gives visibility to the operator of the blockchain, so that that it can meet its obligations for anti-money laundering and fraud monitoring, but because the central bank is one step removed, we can guarantee privacy from the eyes of the central bank and the government.

If each of the participants in the central bank blockchain operates a second layer blockchain of its own, it builds into an entire system of permissioned and public blockchains. It can define clear perimeters for governance, with clear responsibilities for operators of the permissioned blockchains. The system can use the central bank infrastructure for settlement between chains in real time. And it offers connectivity to, and composability with, the public blockchain ecosystem, with all that has to offer in terms of access to tokenised assets.

A triangle of trust

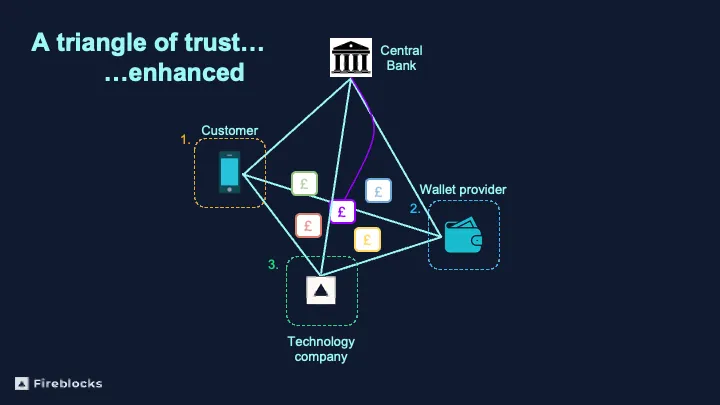

Let me turn to wallet infrastructure, and what I believe is one of the final pieces of the puzzle in the transition towards Web 3, or direct ownership of data, content and assets. In a technological setup we (and others) offer to the market today, we can give customers direct ownership of their funds, protected by a triangle of trust. This triangle of trust is incredibly powerful, because it offers resilience to operational and financial risks - and nothing gets a regulator more excited than operational and financial resilience!

The customer is responsible for remembering their password and keeping their device safe and updated. A wallet provider provides a user-friendly interface and is responsible for customer onboarding, fraud monitoring, compliance, and handling customer complaints. And a technology provider is responsible for the infrastructure that holds it together and the cybersecurity that helps to protect the customer’s private key.

- If the customer forgets their password or loses their device, they can turn to the wallet provider for help, much as they do today. They can go through a process to recover their password and re-establish control of their wallet.

- If the Wallet Provider suffers a prolonged outage or any other significant operational failure, the customer can turn to the technology provider, to re-establish control of their assets and take them to another wallet provider.

- And if the technology company suffers a prolonged outage or significant operational failure, the customer can resort to a disaster recovery service, provided by an independent 3rd party, like an insurance service, to re-establish control of their assets and take them to another wallet technology service.

What is really powerful about this set up is that the customer has no financial exposure to any of the other parties. The customer has direct ownership of their funds in all scenarios. This is clever because it separates financial risks and operational risks - it means that the wallet provider does not need to be regulated like a bank and lowers the barriers to entry and exit, ensuring competition and consumer choice in the market for wallets.

It also means that the customer can hold all sorts of digital assets in this way, including all those forms of tokenised money we spoke about earlier. And if we give the customer access to a retail CBDC, they can hold the lowest risk asset in the land and minimise their exposure to financial risk. But they also have choice, so they can choose whether to spend in CBDC, or tokenised deposits or stablecoins, as they see fit, delivering a true vision for Web 3!

Conclusion

I started this blog by quoting the great Yuval Noah Harrare. And I’ll end with a quote too, this time from the great children’s TV show, Bluey. In an episode about Promises and Trust, Bluey’s mum says “without trust, none of this would be possible: no libraries, no roads, no electricity”. And she was right.

Our societies are built on trust. And money is central to that. Central banks around the world have the opportunity to upgrade our payments and financial systems for the future. Trust is hard earned - and thanks to the private sector alternatives to CBDC, central banks will have to work hard to demonstrate that we can trust in the new forms of money they issue, both in terms of their value and their protection of our civil rights.

But I hope I have shown that there is a way forward, that leverages the latest advances in blockchains and wallets, and that it can be achieved as a collective effort between the public and private sectors. Working together and underpinned by trust, we can build amazing things in the future too!