27 April 2020

Contact Tracing Apps: Should we embrace Surveillance?

Dr Mercedes Bunz

An extract from a long read about the risk of Covid19 contact tracing apps normalising surveillance.

‘Media show up wherever we humans face the unmanageable mortality of our material existence,’ wrote the philosopher John Peters Durham five years ago, not knowing that the Coronavirus Covid-19 would prove him right.

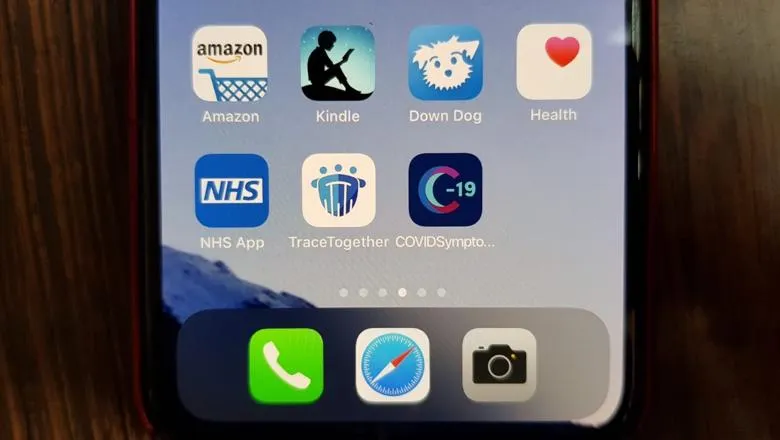

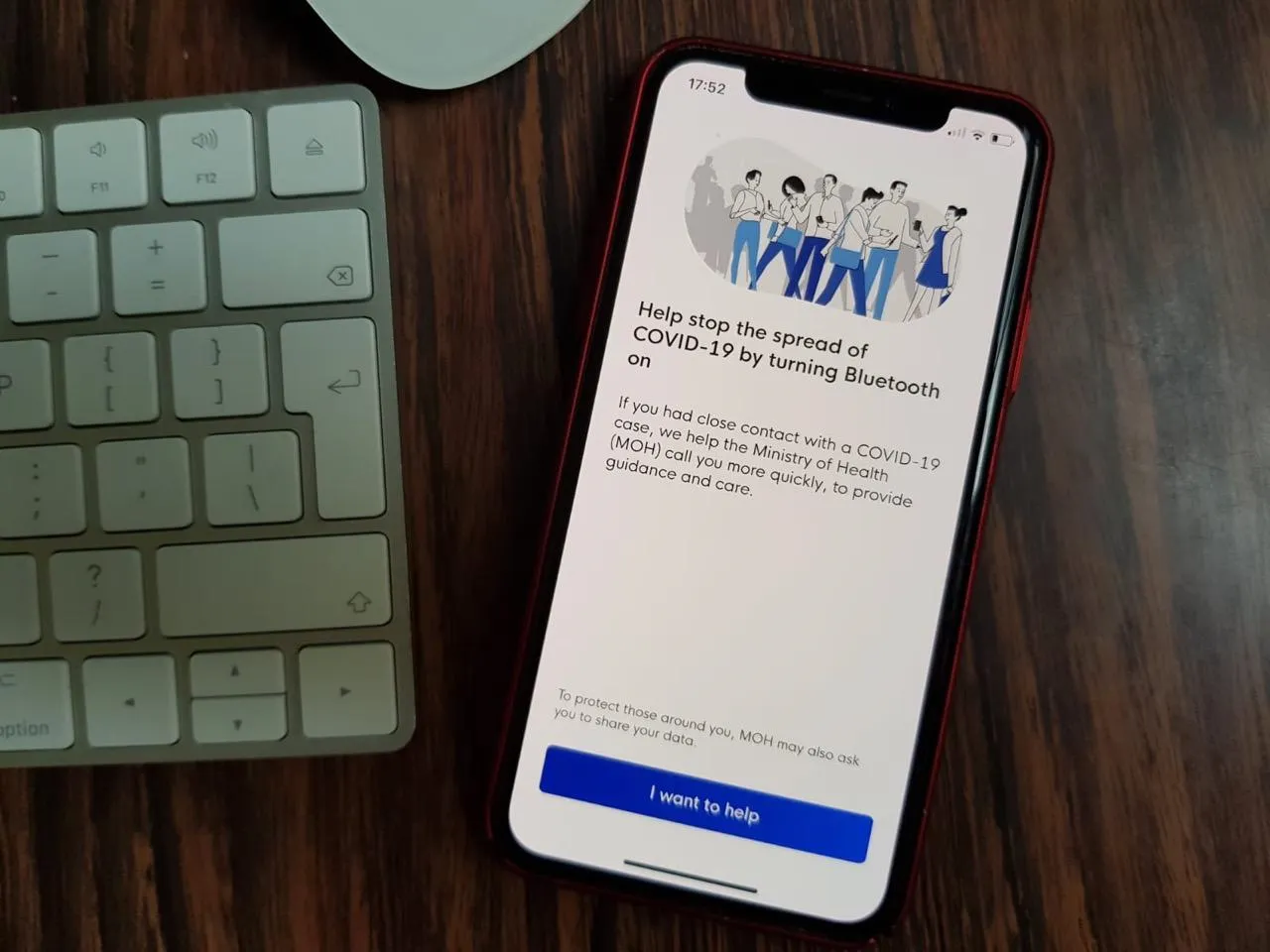

By the beginning of February there was an app for assisting us in managing our mortality better, and as it usually is with apps, soon there were too many of them to keep track. There were apps that tracked your symptoms. Apps that calculated the likeliness of you having Covid-19 out of thin air. Apps that informed you about the coronavirus spread in your area crunching recent data. And apps that warned you rightly or wrongly about having come in contact with a carrier of Covid-19. All over the world governments were looking into how to best track the infections of their citizens. Thanks to COVID-19, surveillance seemed to have become acceptable. Even the EU, so far the leading in the fight for privacy and data protection, adapted to this tune. Its GDPR law had set a new standard influencing the handling of data worldwide. That was then. Now its European Data Protection Supervisor stated that Covid-19 is a moment in which ‘you realise the world has changed’. And the apps on our smartphones were the game changer.

Covid-19? There is an app for it

There are reasonable fears of an intensification of surveillance: we know that measures to fight a disease are deeply linked to political ideologies, described for example in Richard Evan’s study Death in Hamburg: Society and Politics in the Cholera Years 1830-1910 (brilliantly summarised by Alex de Waal) and more prominently in Michael Foucault’s Discipline and Punish. Foucault showed how the chaos of the plague, ‘at once real and imaginary’ is met by order: by issuing regulations, by confining the population to quarantine leading to the ideology of a disciplined society. Before that, the measures to fight another disease, leprosy, resulted in excluding the infected by marking them through special clothing, ringing bells to warn others that they were close, or in exiling the potentially sick in an asylum leading to the ideology of a pure community. In the fight against Covid-19, those older measures returned: ‘lockdown’ and ‘social distancing’ are modern version of the quarantine, while the closing of national borders, which promptly fuelled racist incidents, echoes the wrong idea of a ‘pure community’. But there is also a new and original element to this crisis drawing on the technological society we have become: a digital track-and-trace of the virus typical for the society we live in, the ‘society of control’, as Foucault’s friend and colleague Deleuze put it. It is enabled by the devices that rarely leave our sides allowing ‘continuous control’ and ‘instant communication’: our smartphones.

Every 12min of our waking day

The infrastructure for such a measure to curb the new pandemic via our smartphones is well in place, providing reason for both hopes and fears of tackling Covid-19. The device has been widely adopted: nearly 80% of people living in the UK own a smartphone. It is also the device people say they would miss the most, according to an Ofcom report, which also found that on average people in the UK check their smartphones every 12 minutes of the waking day. This strong bond with our smartphones, previously condemned as an ‘addiction’, now seems to be an advantage when it comes to tackling COVID-19. With a few technical tweaks, apps could continuously as well as instantly deliver tailored communication to smartphone owners; such as the news that we have come in contact with a carrier of the virus or if we are getting close to a location where a carrier has just been. The fear that COVID-19 accelerates the existing normalisation of surveillance and data capture even more is not just scaremongering – it is real.

Emergency legislations introduced to manage the crisis often include the widening of possible surveillance. When the UK government was summarising the impact of its own legislation, it acknowledged that this ‘could lead to increased interference with citizens’ Article 8 rights to privacy’. Still, the legislation will not be reviewed before two years. The crisis also allows technology companies to scale up their techniques of capturing data, now for a good cause. Can surveillance be justified? Whatever happened to surveillance? Given the worldwide quarantine we humans find ourselves in, afraid of a virus and without a vaccine, tech solutions are being looked upon as a possible solution. They are also being embraced and implemented without the usual scrutiny. The NHS announced to work with US tech companies such as Palantir, Microsoft, and Amazon to process data and inform the COVID-19 response. This has been met by strong criticism from digital rights groups and critical tech experts. At the same time, studies by epidemiologist which calculate models to understand the transmission of the virus in better detail came to the conclusion that certain forms of surveillance might be the only measure to contain the disease.

To read the full article from Dr Mercedes Bunz, visit the KCL Digital Humanities blog