23 April 2019

Getting people to respond to government consultations: when a nudge becomes a shove in the wrong direction

Annabelle Wittels and Dr Michael Sanders

ANNABELLE WITTELS and MICHAEL SANDERS: Brevity is a virtue

In a time of populism and fake news, it can often seem that government isn’t listening to the concerns of those it serves, and that policy is developed without proper consultation with the people it will affect.

This characterisation isn’t entirely fair. Cass Sunstein, author of Nudge, said at last year’s behavioural exchange conference in Sydney one thing that surprised him when he came into the Obama administration for the first time was how much consultation there was and how seriously it was taken by officials.

What certainly is fair is that these consultations do not always reach everyone, and people can find them difficult to engage with. Consultations are like TripAdvisor reviews for democracy. Everyone agrees that they are important to decide where to go and what to do but no one wants to be the one leaving the review. Imagine policy was made that way!

The third runway consultation for Heathrow is one rare exception where the consulting body is inundated by comments and ideas. But most consultations go unnoticed by the wider public and often by the very citizens who they concern.

To try and help overcome the barriers, we worked on a consultation with a large government department last year. Most consultations today use email and online surveys. We tested whether embedding behavioural messages in emails can encourage public sector professionals to reply to a consultation whose results were to be the base for policies that would affect them and their clients. In this large-scale experiment, we tested four different messages – a “standard” email, which we’d written to make it easy to understand and reply to, and three messages which drew on insights from behavioural science – reciprocity, identity theory, and pro-social preferences.

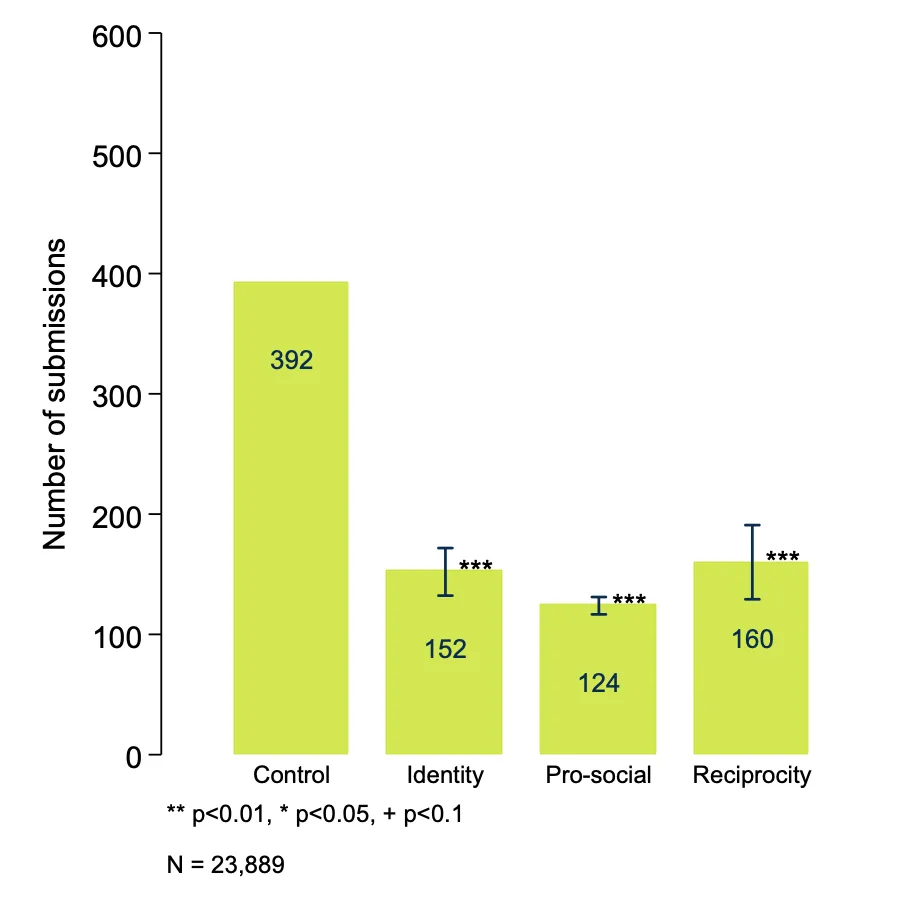

The messages were sent out to more than 20,000 professionals, and we watched as their responses came in – with the results shown in the graph below.

There was some good news, and some bad news. The good news was that the standard email performed well, significantly increasing response rates compared with previous attempts by our partner to get responses. The bad news, however, was that all of our behavioural insights backfired, leading to significantly lower levels of response.

Looking at the data in a bit more detail, we found that the longer, and more complicated the email subject line, the fewer responses we were getting. The behavioural messages also made it more difficult to quickly discern what the ask and potential impact of responding were – reasons that Vivien Lowndes, an academic who studied consultation processes across the UK, found to be core concerns of citizens who are hesitant to participate. One of us ran a randomised control trial with a large city authority in the UK and found similar evidence – convincing people that their voice matters is key.

We need to do more research in this area, but the implication for now seems to be straightforward: if governments want people to talk to them, they need to demonstrate that they will listen, and, to quote Calvin Coolidge, be brief – above all things – be brief.

Annabelle Wittels is a Doctoral Student at the UCL School of Public Policy and a Research Fellow at the Behavioural Insights Team.

Dr Michael Sanders is a Reader in Public Policy at the Policy Institute, King’s College London, and Executive Director of the What Works Centre for Children’s Social Care. He previously served as Chief Scientist at the Behavioural Insights Team.