07 April 2020

How coronavirus upended UK economic policy

Torsten Bell and Laura Gardiner

TORSTEN BELL and LAURA GARDINER: Recent policy announcements would have seemed unimaginable just weeks ago

Britain, like many countries around the world, is in a sharp recession. The very unusual thing about this recession is that we are doing it to ourselves, with government shutting down significant parts of our economy to stop the spread of coronavirus and save lives. And while the virus does not discriminate between rich and poor, this economic impact certainly does. The sectors hardest hit by the lockdown have typical weekly pay of £320 – well below the national average of £455.

We cannot ask people – particularly lower earners – to help us save lives if we do not show them how we will save their livelihoods. That is why in recent weeks the government has made a number of policy announcements that would have seemed unimaginable just weeks before. A Conservative government is underwriting 80 per cent of the wages of workers in struggling firms, offering cheques of up to £7,500 to most self-employed people, and lifting the main rate of out-of-work benefit to its highest-ever level. This is where the inescapable moral and economic logic of a pandemic-driven recession have brought us.

Let’s take the three pillars of this response for supporting family incomes in turn. First, the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme, under which the government will pay 80 per cent of the previous wages of employees without work to do, up to a high cap of £2,500 per month. Since the initial announcement, the government has provided the welcome detail that this scheme will cover people on zero-hours and agency contracts, and those who have already been laid off, who can be re-hired to go onto the scheme.

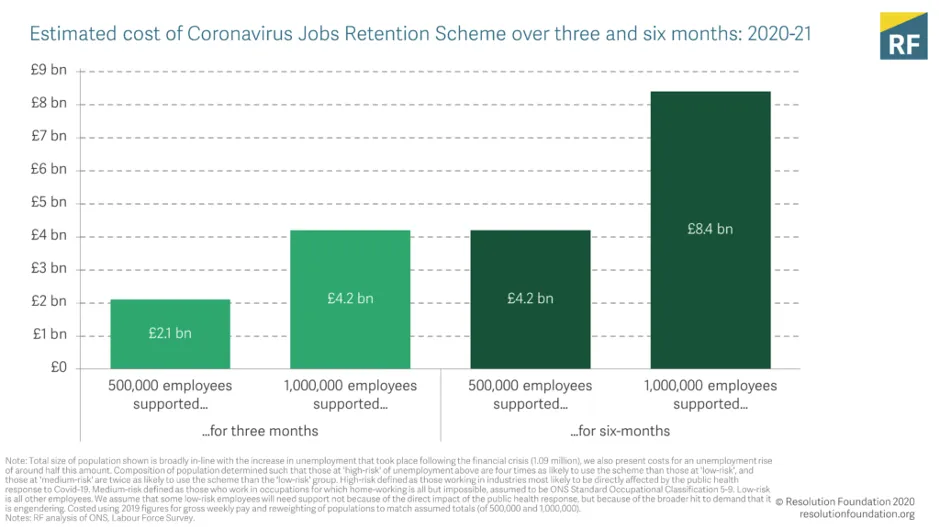

While the cost ultimately depends on how many firms take up the scheme, and for how long, we estimate that should it support 1 million employees it would cost around £4.2 billion over the initial three-month period the government has set out it will run for. The eventual caseloads will be many times that level so the eventual costs of the scheme will be too.

This scheme is hugely welcome because as well as helping the individual workers concerned, it will also reduce the scale of the coming recession by reducing falls in consumption that cause wider economic damage. Critically, keeping workers on payroll will also help firms to recover quicker once the worst of the crisis is over.

The second pillar of the government’s support package came a week later, with the announcement of the Self-Employed Income Support Scheme. This will pay cash grants covering 80 per cent of self-employed trading profits over three months, averaged over up to three years of tax returns. This scheme has the same £2,500 per month cap as the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme, but adds in further exclusions for high earners and those incorporated as businesses.

This scheme is in some ways more generous than that for employees – arguably too generous. Although it was pitched as being targeted at self-employed workers affected by the coronavirus outbreak, in practice self-employed people will be able to claim a grant irrespective of whether their income has actually fallen. This blanket payment approach means that the costs will be high, although also highly uncertain. HM Revenue and Customs data on self-employed earnings suggests that it could cost around £10 billion over three months if everyone entitled to it claimed.

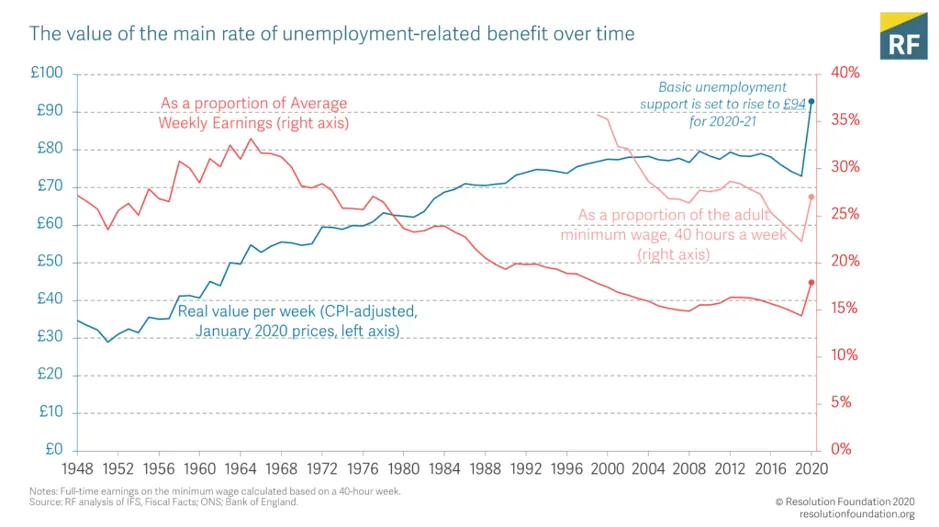

The third pillar of the government’s unprecedented package is a £20 per week increase in the main rate of out-of-work benefit, alongside an increase in housing support, coming at a cost of around £7 billion. This takes unemployment support to its highest real-terms value ever, after two decades of stagnation or decline.

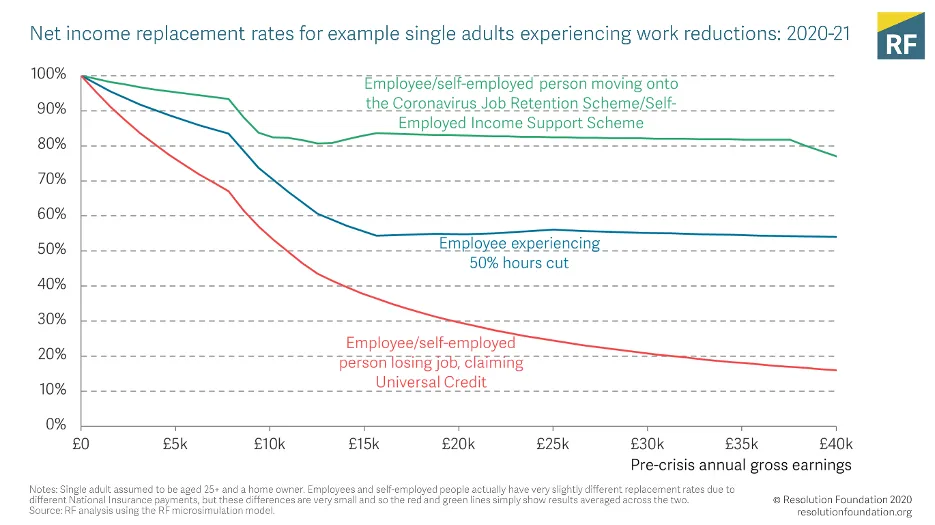

These three pillars make for a strong platform, but despite the truly unprecedented nature of the government’s response to date, gaps and cracks remain. Employees who experience hours cuts but whose hours do not fall to zero currently get no support under the job retention scheme. This creates an unwelcome economic incentive for them to ask their employer if they can cease work entirely, which risks deepening the economic shock that Britain is experiencing.

Also missing out on the job retention scheme will be those who lose their jobs despite its existence, for example because their employer goes bust. And those who only became self-employed in the recent past and so have no tax return for the 2018-19 financial year are not eligible for the self-employment support package. The only source of support for these groups is the welfare system, which offers far lower income replacement rates (the level of prior income families hold onto should work dry up) than the newly announced employee and self-employed support schemes, despite recent benefit uplifts.

This means that as well as extending the job retention scheme to those facing reduced hours, the government should prioritise extending the Self-Employed Income Support Scheme to employees losing their jobs, on the basis of previous pay checks (which the government has access to as part of its earnings data collection). For everyone else, including the newly self-employed, swift receipt of social security support is the urgent priority. To this end, the government should relax savings means tests so that more families are eligible for support, and make benefit advances payable by default as well as pausing the repayment of these for the duration of the crisis.

Beyond these changes, the broader consideration for when the virus recedes is where our state and politics will go next. In some areas, the passing of the emergency should lead to the state stepping back – we certainly don’t want the Treasury to be permanently underwriting the wages of firms that fail. But in other areas, it has taken a crisis to make us do the right thing. Those losing their jobs a few weeks ago faced a social security safety net not fit for purpose, with the main rate of unemployment benefit lower in real terms than in the early 1990s, despite our economy being 50 per cent bigger per person. We must never return to that state of affairs.

Stepping back from the policy details, the government has very swiftly made the decision to collectivise the economic pain of a crisis that it has in a sense created, due to the necessary lockdown measures in place. There are tweaks that policymakers should make to ensure that some families don’t fall through the cracks. But the key conclusion remains that, economic and morally, the British state has acted decisively to support family incomes at the same time as saving lives.

Torsten Bell is Director of the Resolution Foundation.

Laura Gardiner is Research Director at the Resolution Foundation.