Severe hypoglycaemia is a life-threatening emergency and it, with IAH, can be devastating for people with type 1 diabetes and for their families. The brain imaging studies have helped us understand why about 1 in 10 people with type 1 diabetes struggle so much with problematic hypoglycaemia and have underpinned a research programme that has led us to a novel treatment with exciting potential to help these people. It may also have implications for other conditions where failure to experience symptoms leads people to recurrent severe exacerbations of disease.

Professor Stephanie Amiel

23 May 2018

King's research uncovers new links between diabetes and mental health

Will Richard, Communications & Engagement Officer

New research identifies key areas of the brain that change patients’ ability to recognise hypoglycaemia.

New research co-authored by Professor Stephanie Amiel, RD Lawrence Professor of Diabetic Medicine, and published in Diabetologia identifies key areas of the brain that change patients’ ability to recognise hypoglycaemia.

People with type 1 diabetes are often unable to regulate their blood sugar so it can become dangerously high (hyperglycemia) or dangerously low (hypoglycaemia). If left untreated, blood sugar levels can fall below the threshold for maintaining brain function leading to unconsciousness and even death.

The best defence against severe hypoglycaemia is someone recognising the early symptoms such as dizziness, trembling and blurred vision and taking action themselves. This usually involves having a sugary snack and then monitoring blood sugar levels to ensure they recover. Some people, however, suffer from Impaired Awareness of Hypoglycaemia (IAH) which means they are unable to recognise these warning signs.

IAH increases the risk of severe hypoglycaemia developing sixfold and can be resistant to clinical intervention. It is reported in as many as 40 percent of people with longstanding type 1 diabetes: more than 15 million people worldwide.

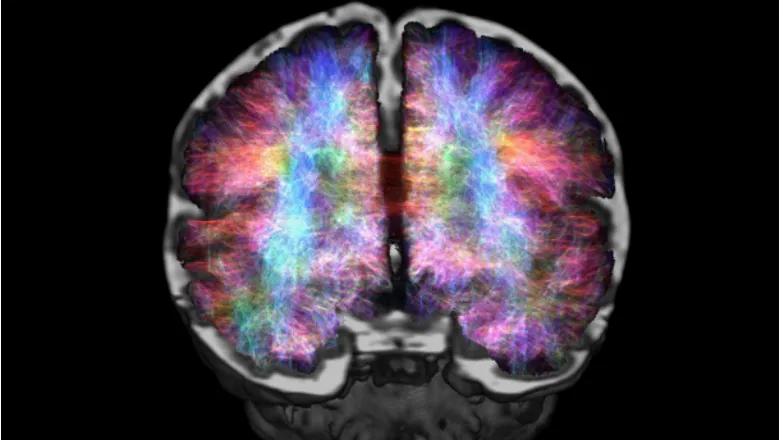

To better understand how this occurs Professor Amiel and her colleagues used Positron Emission Tomography and radiolabelled water to identify regional changes in brain activity. They studied 17 men with type 1 diabetes, eight with IAH and nine with normal hypoglycaemia awareness (HA), during periods of healthy blood sugar levels, induced hypoglycaemia and recovery. By tracking the radioactivity, the authors were able to measure changes in blood-flow in different regions of the brain.

Participants with IAH showed significantly less activity in specific areas, particularly regions associated with subjective awareness, emotional experience, aversiveness and memory. These results suggest that not only are people with IAH unable to recognise the symptoms of hypoglycaemia but they are also unable to recall previous episodes as particularly unpleasant or disturbing.

This could explain why IAH has historically been difficult to treat, as traditional methods have ignored the apparent emotional and cognitive elements of a patient’s complex response. Professor Amiel’s team, in the School of Life Course Sciences, have recently embarked on a trial, funded by the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF), of a novel treatment which takes account of these to help people with IAH avoid future hypoglycaemia and recover their awareness.

Speaking of the study Professor Amiel said: