04 September 2025

Remembering Professor Jack Spence

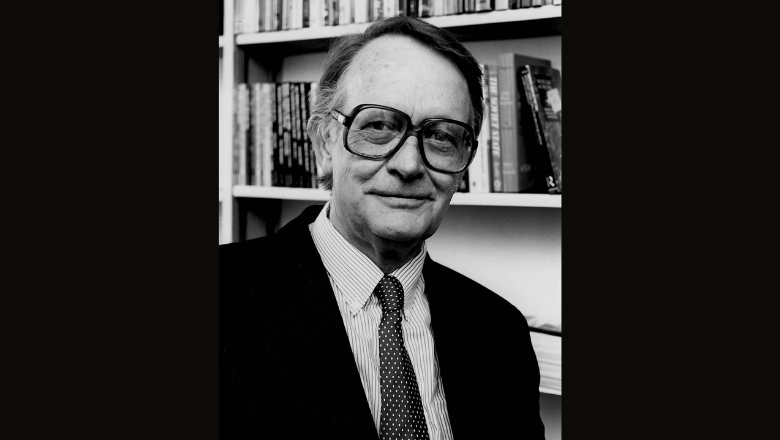

We pay tribute to Professor Jack Spence, who passed away in August this year.

Professor Jack Spence, who for 25 years was an adored figure in the Department of War Studies at King’s College London, died on 15 August 2025, aged 94. He only came to King’s in ‘afterlife’. He had already had an eminent career. This included retiring as Director of Studies at Chatham House (the Royal Institute for International Affairs) and editor of its flagship journal International Affairs, in 1997. By the time of Jack’s retirement from King’s, celebrated in 2022 (his second – and final – retirement), he had been one of the leading figures in International Relations for over 60 years. He had been awarded three honorary doctorates and four honorary fellowships. One was from King’s College London. His work covered theory and practice, with focuses on international politics, diplomacy, nationalism, Africa, war and defence education, and poetry and literature.

Jack was born in South Africa, growing up in the mining town of Krugersdorp. He attended Pretoria Boys High School and the University of Witwatersrand. He graduated from the latter in 1952 with a BA. For the next step, he would come to London, following a conversation with a fellow student in what Jack described as the ‘real backwater’ of Witwatersrand. That conversation opened a whole new world. The colleague had some document about a place called the London School of Economics. ‘We had never heard of it, didn’t imagine that there was such a place,’ Jack told me when we last met, just after his final birthday. The friend had urged him to go. He saw how Jack could thrive. Jack applied, came to the LSE and graduated with a BSc Econ in 1957.

The greatest achievement of his time at the LSE, without any doubt in Jack’s view, was meeting his wife, Sue. She came from a comfortable background — although her father had died in the Second World War, her mother owned and single-handedly ran three clothing shops very successfully in what John Betjeman called ‘Metroland’, the areas on the north-west periphery of London. It was Sue’s decision that they should go to his homeland, South Africa — as Jack told me: ‘It was she who decided — she decided everything, always, moving back, moving to Ludlow; I was very lucky, I just followed and did what she said, and it all just worked out.’ In South Africa, Jack had a post at the University of Natal (1958–60). But both were liberal activists. She was general secretary of the Liberal Party, the only party in South Africa open to all and without racial affiliation. Liberalism was an important feature of Jack’s life and thinking — in his last years, he continued to reflect and work on the idea. He and I planned to write an article or even a book. We had just started and last discussed it only recently before he passed away. Jack was intellectually liberal. But, most of all, he was essentially liberal in his spirit and being. In a term he used to describe someone else, Jack was himself an ‘instinctive liberal.’ He was gentle and open, the embodiment of ‘live and let live.’

After Natal, with Sue deciding, they returned to London for Jack to become a Rockefeller Junior Fellow at the LSE, in 1961. A year later, his career was established. He gained a lectureship at the University of Wales, Swansea (now Swansea University). He went on to become Senior Lecturer there. In 1973, he moved to the University of Leicester, where he was Professor of Politics and Head of Department from 1973. He was appointed Pro-Vice Chancellor in 1981. He served in that senior leadership role until leaving in 1991 to join Chatham House.

Jack had many other highly significant roles along the way, confirming him at the forefront of international studies. He was: Chairman of the British International Studies Association (BISA) — he enjoyed giving the keynote lecture at the 1992 annual conference, returning to the place where he had his first permanent post; President of the African Studies Association of the UK (ASAUK), 1981; a member and Chairman of the Advisory Board of the David Davies Institute, London; a member of the Advisory Board of the ESRC Transnational Communities project; and Chairman of the International Advisory Board of the Association for the Study of Ethnicity and Nationalism. This was a role he diplomatically nominated me to take on in 2007. He stood down after 16 years. In addition, he had positions as Visiting Professor at the Universities of California, Los Angeles (1965 and 1970); Zimbabwe (1978); Witwatersrand (1980 and 1985); Cape Town (1982 and 1986); Natal (1985 and 1988); Pretoria (1997).

However, it was his role as Academic Director at the Royal College of Defence Studies (RCDS), carried out alongside his roles at Chatham House and, later, King’s, that led to his being awarded the OBE in the 2003 New Year Honours List. Throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s, Jack advised the Commandant. He helped significantly to develop the intellectual component of the programme. One aspect of this was a move to publish the Seaford House Papers until 2002, which he edited. It presented to the world some of the best research papers prepared at RCDS. In this time, he also helped to foster a move towards academic partnership, established after competition, with the Department of War Studies at King’s College London.

Although the process had begun before, by the time King’s began providing academic support to RCDS in 2001, Jack was already working in War Studies as well. He had joined in 1997 after a conversation he and I shared at a Strategic Defence Review gathering at a club on Pall Mall. He was literally just retiring from Chatham House. I had just completed development of a new MA programme — the first of what would become 15 or more such programmes going beyond the original MA War Studies. I had designed half a dozen new courses, and these would need teachers. So, I suggested that Jack might help. And he could. Professor Christopher Bogaert (Dandeker) was Head of Department at that stage, and he leapt at the chance to bring Jack on board. He had benefited from Jack’s wisdom and benevolence as a lecturer at Leicester. There, Jack’s ‘liberal’ and open approach had saved Christopher from being stifled. He brought him into the open and eclectic politics department. His work on civil-military relations could thrive there. As Christopher noted on hearing of Jack’s death, ‘He saved my career at Leicester… and did us proud at King’s.’ It was perhaps inevitable that Jack should eventually join War Studies, given that his inaugural lecture at Leicester was titled ‘War is too Serious ...’ Everyone at King’s enjoyed the relationship with Jack — most of all, the students. Envisaged as a short-term temporary move for Jack, given that he had already retired, he remained as Professor at King’s for a quarter of a century. The Diplomacy course became his — and was so popular that in some years he had to run it two or three times to accommodate the students’ eagerness to take it. Students adored him because of his gentle manner, his calm authority, his immense erudition and standing. And, of course, because he loved to go with them to Daly’s Wine Bar just down the Strand, or to a pub, continuing discussions long into the evening.

The wine bar was also important for developing one of Jack’s later academic contributions, the two-volume New Theory and Practice of Diplomacy: New Perspectives on Diplomacy, co-edited with Claire Yorke and Alistair Masser, who had been students in War Studies. They were devoted to Jack, as he was to them, as he mentored them as teaching assistants and young researchers. Each developed significant careers, one as an academic, the other as policy advisor and analyst. Mentoring was an important part of Jack’s life. Among the many others he supported along the way was a fellow South African, Mervyn Frost, who would join us at King’s as Professor of International Relations, in 2003, after establishing his eminence in the field at other universities. He would go on to succeed Christopher Bogaert as Head of Department. However, perhaps the greatest achievement as mentor was his support for Funmi Olonisakin, from examining her PhD to her becoming Professor and Vice-President (International and Engagement) at King’s. This demonstrated his pan-African approach, as this Nigerian woman became a pioneer for black academics in the UK. She was the first black Professor at King’s, the first black woman in a college leadership role, as well as a member of two UN Secretary General’s working groups. As she said at Jack’s retirement celebration in 2022: ‘I couldn’t have done what I have done without the support of three white men… Jack helped me so many ways, linking me with Pretoria, always encouraging.’

As well as the ‘Diplomacy’ volume, Jack published seven books and monographs, as well as over sixty articles and book chapters in the domains of Strategic Studies; International Relations; British Politics; Literature and Politics; and Arms Control. His best-known book was probably the one that encapsulated his life and liberalism, Ending Apartheid, co-authored with David Welsh and published in 2010. As well as working on the Liberalism article, he was still writing book reviews for International Affairs, the journal he had edited, in the weeks before he died. As Claire Yorke put it, ‘He was so tenacious and consistently excited by ideas.’ He was. Always engaged, entirely polite, soft and understanding, Jack was an exemplary scholar and individual, a ‘gentleman of the old school’ who had a ‘good, long life’, as Christopher Bogaert put it. He was, as he was known, ‘Gentleman Jack.’

Jack was married and devoted to Sue for over 60 years. She pre-deceased him in 2021. He is survived by his daughter Rachel.

This piece was written by Professor James Gow, Professor of International Peace and Security in the Department of War Studies, King's College London.