14 March 2023

Should we be worried about a rise in the perceived justifiability of suicide?

Michael Sanders

Thankfully the data suggests concerns may be misplaced

New data from the UK in the World Values Survey programme, published by the Policy Institute in partnership with a consortium of other research organisations, shows a rise in the share of the British public who say that suicide is “justifiable”. 16% felt this way in 2022, compared with 6% in 1981. And perhaps most strikingly, Gen Z – the youngest generation of Britons born from 1996 onwards – stand out as considerably more likely to feel this way, with 30% of this cohort believing suicide is justifiable.

This has led to some concern. For example, Professor David Halpern, Chief Executive of the Behavioural Insights Team (who is on the advisory board for the UK in the WVS project), has suggested this rise in perceived justifiability of suicide may lead to a rise in actual suicides.

David’s concern is not without foundation. His 1997 paper looks at the association between societal suicide tolerance and the level of suicide and finds a significant and positive association, ie that more tolerance of suicide is associated with more suicides taking place. Similarly, a 2022 paper finds that reductions in the stigma around suicide are associated with greater “normalisation” of suicide, which they suggest might lead to a rise in suicide itself. Neither of these papers suggests a causal link – its data is not strong enough to support that conclusion – but it should give us a moment’s pause.

Thankfully, the rest of the data suggests we needn’t be that worried about it. The 1997 paper makes use of 1989-1990 WVS data and national suicide rates from 19 countries. The fact that we’re able to follow values across long time periods and see how things evolve over time is one of the major strengths of the WVS, and this is just one of hundreds of reasons to continue to collect this data. It means that we have the same definition of suicide tolerance over time.

At the time, there was no more than 10% of the three active generations (pre-war, Baby Boomers and Gen X) considered suicide to be justifiable. Today, none of the five active generations (the same three plus Millennials and Gen Z), have tolerance levels of less than 10%. The pre-war generation have receded in their numbers, and remain the generation least likely to say suicide is justifiable, but even their tolerance has more than doubled over the last 30 years, albeit from a very low starting point.

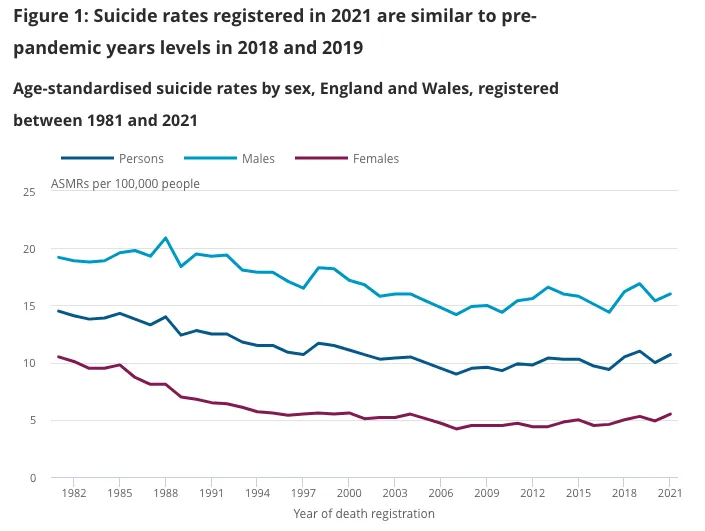

If the previous association holds, then we would expect the rate of suicides to have risen over the same period. Thankfully, this is not what we see. In 1989-1990, suicide rates stood at 12.6 per 100,000 (adjusted for the population’s age profile). In the most recent ONS data, this stood at 10.7 – 15% lower. This is a little higher than its 2017 nadir of 9.7, but overall, the pattern is one of declining suicide rates.

Suicide rates among people aged 10-24 (who have the highest suicide tolerance), have been rising in recent years – starting 2007 for girls/young women and 2010 for boys. This is troubling, but difficult to attribute to the "normalisation" of suicide among young people. Since 1990 suicide rates in young people have declined overall, with a small rise in rates for young women and girls offset more than twice over by a fall in the rates for young men and boys.

This is important, not just because being careful with statistics is a good thing to do. Stigma around mental health (arguably the opposite of tolerance), is not a positive thing. Knowing that our friends, family, colleagues, and society, are accepting of mental health is an important part of being able to seek support and treatment.

A 2016 survey by YouGov funded by the Mental Health Foundation showed that men are around a quarter less likely to talk to someone about their mental health challenges than women. They are also, tragically, about three times as likely to commit suicide. Tackling ill mental health and suicide cannot be done in silence, and talking requires tolerance.

If you are experiencing thoughts of suicide you can get in touch with a non-judgemental listening services for support.

For students, many universities have a dedicated nightline listening service. For everyone else, you can contact the Samaritans.

If you think that a friend or loved one might be experiencing low mood or depression, I recommend “Are you Really OK?”, by Roman Kemp.

Michael Sanders is Professor of Public Policy and Director of the Experimental Government Team in the Policy Institute at King’s College London, and an Evidence Associate at What Works Centre for Wellbeing. He is also Chair of Trustees of the Nightline Association, an umbrella organisation supporting student nightlines around the UK. He has written previously about how own experiences of ill mental health.