28 January 2015

Our research has helped inform Government plans about how to communicate with the public during a national health crisis.

Research led by Dr James Rubin

Our research has helped inform Government plans about how to communicate with the public during a national health crisis.

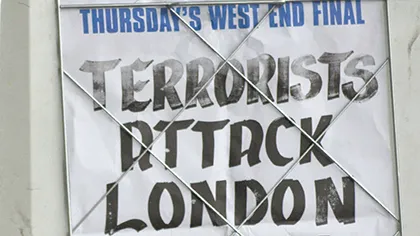

Government plans about how to communicate with the public during a national health crisis – from flu pandemic to terrorist attack – are informed by our research.

Our researchers have two programmes of research about the public response to various potential emergency scenarios. The first involved focus groups discussing five fictional emergencies caused by chlorine gas, smallpox, pneumonic plague, a ‘dirty bomb’ and radiological exposure device (that exposes people to radiation).

The second surveyed public response in the aftermath of real-life incidents including the 7/7 London bombings in 2005; the death of Alexander Litvinenko in 2006 and the exposure of members of the public to radioactive polonium 210; flooding in the north of England in 2007; the outbreak of swine flu in 2009; and the response of British nationals in Japan to the meltdown of the Fukushima nuclear plant in 2011. Some of these surveys have been carried out in collaboration with Ipsos MORI, and most have canvassed the views of about 1,000 people.

‘Our work has highlighted information that people wish to, or need to know immediately following a disaster,’ says Dr James Rubin, Senior Lecturer in the Psychology of Emergency Health Risks.

The research has also illustrated how the content of official statements made during a crisis should be planned, monitored and modified for best effect in the light of feedback from the public. ‘People trust what the Government is saying more if clear, reliable information is released and if officials are not seen to be providing false reassurances,’ says Dr Rubin.

‘Emergency planners often think people will panic and may be over-careful about what information they release. But our work has shown that people generally don’t panic following a major incident. In fact, public apathy may be a much bigger problem – people often don’t take advice in a public health crisis for example.

‘Helping people feel well-informed, however, can make a big difference. It is possible to design reliable and accurate information about specific threats some time in advance, and to test if that information is likely to be understood and be effective, using focus groups and surveys, and then have it ready to get out very quickly in the event of a disaster or emergency. It is also good to monitor the success of communication campaigns as they happen and find ways to improve them. Getting real-time feedback about the effectiveness of information is important particularly if the government is asking the public to do something, such as get vaccinated.’

Dr Rubin and his colleagues are contracted by the Department of Health to gather feedback from the public during the next flu pandemic and are already preparing surveys in readiness. They are also a central part of the new £3.6m Health Protection Research Unit in Emergency Preparedness and Response.

The research team also has an ongoing relationship with the Health Protection Agency and the Cabinet Office: Dr Rubin, for example, sits on the Cabinet Office’s Scientific Advisory Group for Behaviour and the Health Protection Agency’s Psychosocial and Behavioural Issues Expert Advisory Sub-Group. As a result of this work, the team is now a central part of a £3.6m Health Protection Research Unit in Emergency Preparedness and Response.

References

- Rubin GJ et al. Psychological and behavioural reactions to the 7 July London bombings. A cross-sectional survey of a representative sample of Londoners. BMJ, 2005; 331(7517): 60-11

- Rubin GJ et al. Public information needs after the poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko with polonium-210 in London: cross-sectional telephone survey and qualitative analysis. BMJ, 2007; 335(7630): 1143-146

- Paranjothy S et al. Psychosocial impact of the summer 2007 floods in England. BMC Public Health, 2011; 11: 145

- Rubin GJ et al. Anxiety, distress and anger among British nationals in Japan following the Fukushima nuclear accident. Br J Psychiatry, 2012; 201(5): 400-7

- Rubin GJ et al. Public perceptions, anxiety and behavioural change in relation to the swine flu outbreak: A cross-sectional telephone survey. BMJ, 2009; 339: b2651

- Rubin GJ et al The impact of communications about swine flu (influenza A H1N1v) on public responses to the outbreak: Results from 36 national telephone surveys in the UK. Health Technol Assess, 2010; 14(34): 183-266