Preventing deaths from heroin overdose at home

Our research led to governments rolling out take-home naloxone schemes for heroin users at risk of overdose.

22 December 2012

Our researchers showed that supervised medical heroin helps chronic heroin addicts quit the street drug and turn their back on crime, key evidence leading to the treatment being introduced in England.

Research led by Professor John Strang & Dr James Bell

Our researchers showed that supervised medical heroin helps chronic heroin addicts quit the street drug and turn their back on crime, key evidence leading to the treatment being introduced in England.

The work has contributed to mounting evidence from across Europe and North America, and supervised heroin treatment services have now been established in England, Switzerland, The Netherlands, Germany and Denmark.

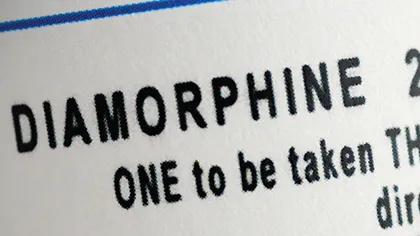

Professor John Strang, and colleagues at the NAC, led the Randomised Injectable Opioid Treatment Trial (RIOTT), which demonstrated that addicts who injected diamorphine under supervision are much more likely to quit street heroin than their peers who are treated with methadone given either by injection or orally.

Methadone is widely used in heroin treatment programmes, but approximately 5 per cent of the estimated 265,000 heroin users in England (in 2014) are resistant to methadone, and they are responsible for the vast majority of drug-related criminal behaviour.

‘Helping entrenched heroin addicts get to grips with their addiction with diamorphine also cuts crime because they no longer need to break the law to fund their habit,’ says Professor Strang. A survey carried out by Ipsos MORI in 2009 showed that, overall, the public support drug treatment programmes in order to reduce criminal activities and make communities safer.

‘In RIOTT, we saw some really impressive examples of change, even within the six-month trial period,’ says Professor Strang. ‘We were able to help people who had been in and out of treatment for years, and the number of crimes they committed was dramatically reduced.’

A previous version of the treatment was available in the UK but, without supervision, the prescribed diamorphine leaked onto the black market. The NAC team worked on a new approach involving close supervision at clinics that would remain open every day of the week. They also developed a urine test that allowed RIOTT researchers to check whether participants were using heroin prescribed by the clinic or bought on the street.

The researchers ran a small pilot study which showed not only a drop in illicit heroin use and criminal activity but also enthusiasm amongst hard-to-treat addicts as a result. A pledge to develop ‘properly supervised heroin prescribing’ was included the UK drugs strategy in 2002.

Since then, the treatment has been promoted in each successive UK government drugs strategy, with a commitment in 2008 to roll out supervised heroin treatment if the RIOTT trial reported good results.

In 2012, the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM) was awarded a three-year contract by the Department of Health to provide supervised heroin treatment in London to addicts who have failed to respond to conventional treatments such as methadone replacement. The aim is to work with SLaM works to offer the service across the capital. ‘We need to work out how to deliver the treatment efficiently over a wide geographical area to a small number of people.’ Two other mental health trusts (in Brighton and Darlington) have been awarded contracts to provide the treatment until 2015.

Although injectable treatments are more expensive to provide, they are associated with reduced levels of criminal activity. Our researchers estimate that the overall savings of providing supervised injectable treatments for chronic heroin addiction in England may be between £29 and £59 million per year.