We must reshape police custody into a space that recognises and responds to the unique needs of children. Reform must be rooted in evidence, and that evidence starts with listening to children and examining their experiences.”

Dr Miranda Bevan, Lecturer in Law at King's

02 July 2025

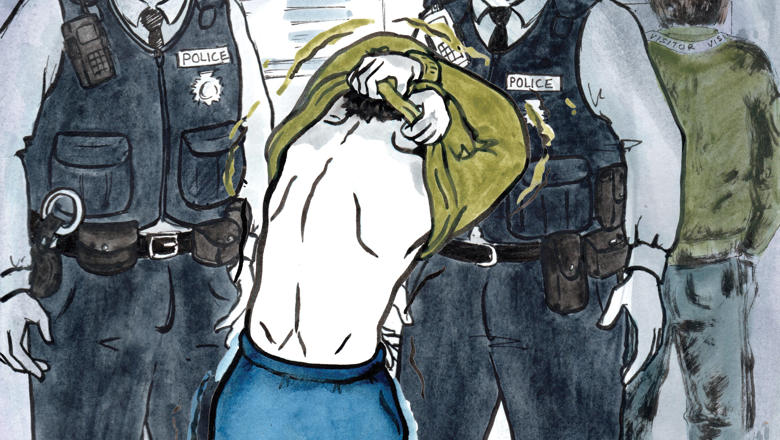

Tighter laws needed for detaining and strip searching children in police custody

Children should not be detained in police custody unless they are arrested for a serious crime – and they should never be strip searched unless the circumstances are truly exceptional.

These are some of the recommendations made at an event in Parliament today by the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Children in Police Custody, chaired by Michelle Welsh MP, as they call for an overhaul of the current legislation governing how young people are treated in police custody.

In England and Wales, children (legally defined as those aged 10-17) are currently subject to the same processes and have essentially the same protections as adults when they are detained in police custody, as per the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE).

Following an inquiry led by Dr Miranda Bevan, Lecturer in Law at King's, looking at the rights of children in police custody, the APPG has launched two reports outlining actions for reform.

They say that police detention should be the last resort for a child and that if they absolutely must be detained, the initial detention period for children should be limited to 12 hours – half of the time that adults can be held.

“Many children are detained unnecessarily and do not experience a process adjusted for their youth and needs,” said Dr Miranda Bevan. “The purpose of detention in the police station is not to punish – children in police custody have not been convicted of an offence, and the vast majority never will be.

“The children who are detained are disproportionately likely to have special educational or communication needs, to have been exploited or suffered victimisation, and to be care-experienced or known to mental health services.

“Yet these children – some as young as 10 – are being left alone in a police cell, with very limited adult support, for up to 24 hours. They are expected to decide whether or not they want to accept legal representation; a decision that they should not be asked to make in those circumstances."

The year-long inquiry involved gathering evidence from children and young people, police forces, practitioners, volunteers and experts in the field, as well as wider engagement work with stakeholders, youth and community groups, non-governmental organisations, and academics.

The APPG heard first-hand experiences from children, including harrowing stories from those who have been strip searched. As a result of the inquiry, the group is calling for a ban on the strip search of children, save in exceptional circumstances.

“It takes extraordinary bravery for children and young people to talk about these experiences and we should listen carefully when they do,” said Michelle Welsh MP.

“Although in police custody strip search is often carried out to ensure the child’s safety, far from feeling safe children and young people described feeling violated and humiliated by the experience, even where officers were respectful in their approach.

Subjecting children to strip search can cause lasting psychological harm, damage their trust in authority, and compound trauma at a critical stage in their development. No child should be made to feel humiliated or unsafe in the very systems meant to protect them.”

Michelle Welsh MP, Chair of the APPG on Children in Police Custody

In the year to March 2024 there were 3,528 strip searches of children in police custody in England and Wales – the equivalent of one child every two and a half hours on average.

The recommendations put forward by the APPG on Children in Police Custody, drawing on examples of good practice by a number of police forces, include amendments to PACE as follows:

- Preventing the detention of children unless they are arrested for an indictable offence, such as a serious violent or sexual offence, and where the child presents a risk of serious harm to others.

- Limiting the initial detention for a child to 12 hours, with the power to extend to 24 hours only with senior officer authorisation.

- Making it a requirement that legal advice be provided for all children detained in police custody.

- Introducing a presumption against child strip search which exposes a child’s ‘intimate parts’, save in exceptional circumstances (defined as being where it is necessary to avoid serious harm, is proportionate and less intrusive alternatives have been exhausted).

The group is also calling for the Home Office to commission a full review of the appropriate adult safeguard, focusing on the role of parents, carers and family members in supporting children in police custody and suitable non-police assistance for them to do so, and for the Ministry of Justice to pilot the introduction of mandatory child specialist training for legal representatives attending children in police custody.

Lord Alex Carlile of Berriew CBE KC, an officer of the APPG, said: “Children are not miniature adults — they are vulnerable, developing individuals who must be treated as such when they come into contact with the criminal justice system. The experience of arrest and detention can be deeply traumatic for a child, and unless handled with compassion and proper safeguards, it risks causing long-term harm.

We must recognise that the current approach too often fails to honour children’s rights and to reflect the fundamental differences between children and adults. Change is not just necessary — it is urgent.”

Lord Alex Carlile of Berriew CBE KC, an officer of the APPG