12 May 2020

What can farmers teach politicians?

Paul-Enguerrand Fady

Farmers have worked with other stakeholders to tackle a huge societal challenge

This piece is written by a member of the Policy Institute's Student Network.

Picture a farmer. Now, try to distil the image in your mind into three key phrases. Depending on who you are, your preconceptions and prejudices, your political and other affiliations, those three phrases will be very different.

Maybe you thought “driver of self-sufficiency”; maybe your first thought was “hard worker, up early”; maybe it was something less complimentary, like “smells of farm animals”! Whatever it was, it seems unlikely your first image of a British farmer was either “agricultural revolutionary” or “our first line of defence against superbugs”. Unsurprising, really, but read on and I’ll show you that not only are these the most important characteristics of the British farmer in 2020, they are also something we can all learn from—not least our politicians.

Specifically, Farmers in the UK are key stakeholders in the challenge to reduce antimicrobial usage. “Antimicrobials” are chemicals that kill bacteria, viruses, parasites and all the other microbes in our environment. The most common antimicrobials you might encounter are antibiotics, though with the current SARS-CoV-2 situation, you may also be intimately familiar with antiseptics, which are found in hand sanitisers.

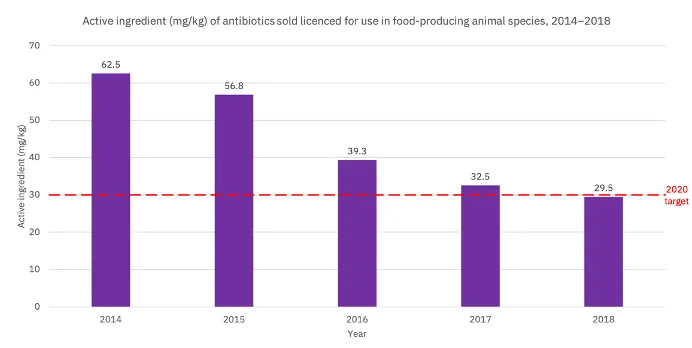

So why, despite statements by the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s adviser to the contrary, are British farmers special and important? Why are they key stakeholders in reducing the use of antimicrobials? Take a look at this chart:

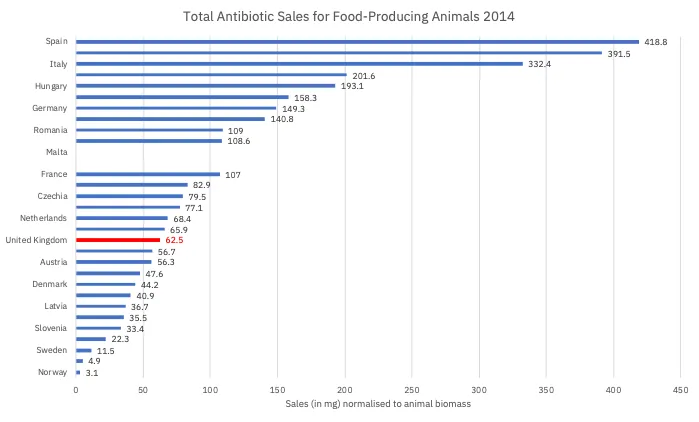

Farmers in the UK have more than halved the amount of antibiotics they give to their animals in less than five years. They did so two years ahead of schedule. That is staggering. What is even more staggering is just how well they did relative to their European peers. Let’s take a look at those same numbers, but contextualised within Europe:

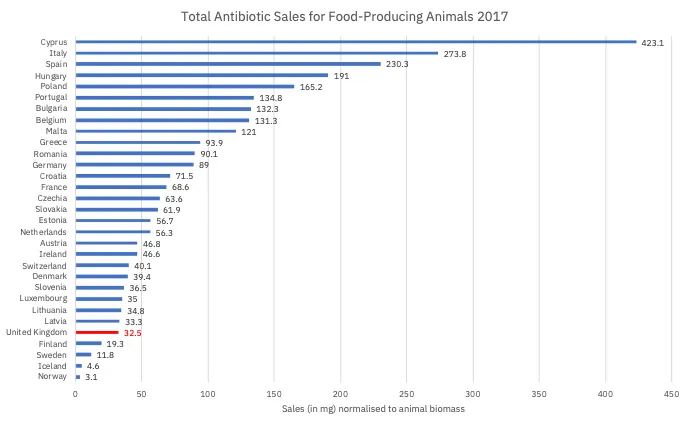

From this we see that the UK was neither in a good nor bad position in 2014, but in the middle. Now consider the 2017 figures:

The UK is a country where large-scale projects (Crossrail, Wembley stadium, HS2, and Universal Credit to name but a few) are famously beset with delays, budget crises and political infighting. So how did farmers manage one of the greatest agricultural overhauls in the 21st century, making the UK a global leader in low-antimicrobials agriculture, in just four years? What can we learn from this amazing achievement?

Farmers did not go it alone. Their smashing success is the consequence of working in close partnership with veterinarians and other stakeholders – a point I will return to shortly. But, as a friend so eloquently asked me during my bi-monthly rant about this achievement, “Are you really still talking about this? Who cares how many antibiotics farmers give their animals?” I argue that it is in all our best interests to care deeply.

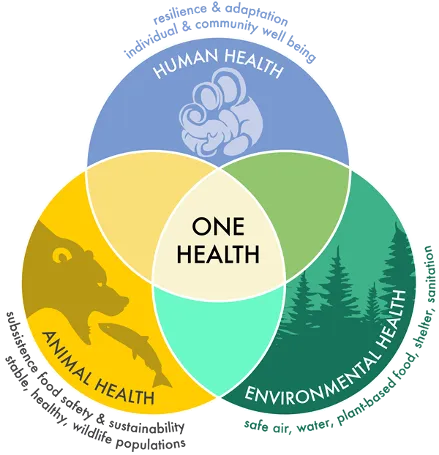

Enter the “One Health Approach”. Broadly speaking, this is a doctrine which holds that the health of all things is interrelated: an unhealthy environment (e.g. polluted soils) leads to unhealthy plants, which in turn leads to unhealthy animals, both of which lead to unhealthy people. The converse is also true: if we have clean skies, soils, and waterways, we have robust ecosystems in which all species can thrive – including humans.

Reducing the quantity of antimicrobials in our environment reduces “selective pressure”. Very simply, some bacteria in the environment can tolerate higher concentrations of antimicrobials through random mutation. These will survive in antimicrobial-polluted settings, while the rest will die. Thus, we are left with a bacterial population which has been artificially selected to resist antimicrobials. The problem is that the antimicrobials we give food-producing animals, the kind which will leak into our environment and apply selective pressures, are the very same ones that we use in hospitals. The same ones we give to children, elderly people, and immunocompromised members of society. The ones that keep us alive—or used to. In fact, a recent study in The Lancet of hospitals in Wuhan has shown that up to 50% of those dying from Covid-19 had secondary bacterial infections (compared to less than 1% of those who survived) despite treatment with these very same antimicrobials.

So, we should celebrate the achievements of UK farmers in reducing antimicrobials use, but more than that, we should try to learn from them. In fact, this radical move to halve the quantity of antimicrobials used in farming in just four years, was a voluntary choice on the part of farmers.

As mentioned earlier, farmers did not do this alone, nor did they do it with particular support or threats from the government. They, alongside other key stakeholders in the One Health approach, leveraged a voluntary framework called the RUMA Alliance (Reducing Use of Medicines in Agriculture). This partnership brings together a range of stakeholders: vets; trade associations; retailers; learned societies; and farmers to work together with the aim of reducing the use of medicines, including antimicrobials.

So what can politicians in Westminster learn from farmers and the RUMA Alliance? In this age of tribalism and party politics, they would do well to follow their example of respectful, multilateral conversation between stakeholders. All of the members of the RUMA Alliance have an interest in animals being healthy and protecting their welfare whilst using as few antibiotics as. This may be for reasons of profit, as in the case of retailers; vocational interest in animal health, like the RSPCA; a combination of both, such as farmers; or other reasons entirely. In any case, in the absence of explicit legislation, these stakeholders gathered independently of government and worked together to achieve benefits in the best interests of the nation. This is not unlike the creation of a multitude of mutual aid groups created to face down the current pandemic.

Affective polarisation has rarely been as high as it has recently in the UK, mirrored by similar situations around the world. Societies are increasingly factional, yet face common issues, giving rise to the perfect storm of conditions for complacency, finger-pointing and blame games to dominate over concrete action. In our own lives, we need to work together with other actors who, regardless of their motivations, want to improve society in the same way as us. We have seen glimmers of such a system in the face of Covid-19, but must ensure that it does not disappear alongside the crisis. We need this type of action for all of the crises we are facing – as Prof. Mariana Mazzucato calls them, “capitalism’s triple crisis” of health, economy, and climate.

Similarly, our politicians need to realise they are all stakeholders in ameliorating life and civil discourse in Britain. Setting aside partisan divisions and coming together to address the real issues facing the UK is crucial for the proper functioning of society. Only with our parliament acting more like RUMA will we see decisive action being taken to concretely benefit people’s lives. Whether they will be as successful in achieving results ahead of schedule remains to be seen…

Paul-Enguerrand Fady is a PhD student in antimicrobial resistance at the Institute of Pharmaceutical Science (KCL) and the Technology Development Group (National Infection Service, PHE). You can read more of his writing on Quora, find him on Twitter (@FadyPEC), or catch him at a Policy Institute Student Network event.

Delivering the UN Sustainable Development Goals

King's College London has a long and proud history of serving the needs and aspirations of society. We are committed to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a university, and we use them as a framework for reporting on our social impact. The SDGs are a set of 17 goals approved by the 193 member states of the United Nations (UN) which aim to transform the world by 2030. This research supports SDGs 2, 16 and 17.