Contact us

Get in touch to find out more.

Do you want to:

If the answer is yes, then join us at King’s!

Doctoral students are automatically members of King’s Doctoral College – from the moment you enrol and for two years after you leave.

1. Research partners in the NHS, business, industry and cultural sector. 2. State-of-the-art clinical, physical and digital research infrastructure. 3. A diverse, vibrant international community. 4. The highest submission & completion rates in the Russell Group. 5. Extensive career support, curated by a team of dedicated careers consultants. 6. Our broad portfolio of leadership, entrepreneurial and developmental training opportunities.

Dr Lienkie Diedericks tells us about her experiences as a PhD student at...

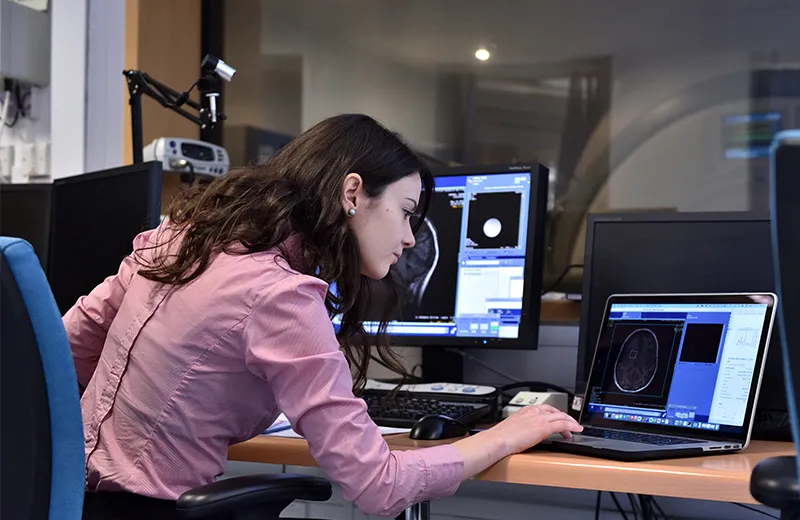

Virginia Fernandez tells us about her experiences of being a postgraduate...

Gabriele La Malfa is a third year PhD student working on a project...

Postgraduate student Hannah Deasy discusses the importance of time...

Final year PhD student, Jie Tang, tells us about her experiences as a...

Lina shares her experiences of her part-time PhD in public policy and...

Dr Maísa Edwards shares her experiences of her Joint International...

Sanchika Campbell shares her experiences of engaging local communities in...

We are delighted to announce the winners of the 2024 King’s Supervisory...

Biological sciences, environmental sciences and physical sciences at...

We are pleased to announce the winners of this years King's Doctoral...