12 November 2020

Adoption Reckonings and Understanding Life Histories

Professor Gonda Van Steen, Director, Centre for Hellenic Studies, is researching the silenced stories of the 3,200 Greek adoptees who were sent to the USA between 1949 and 1962

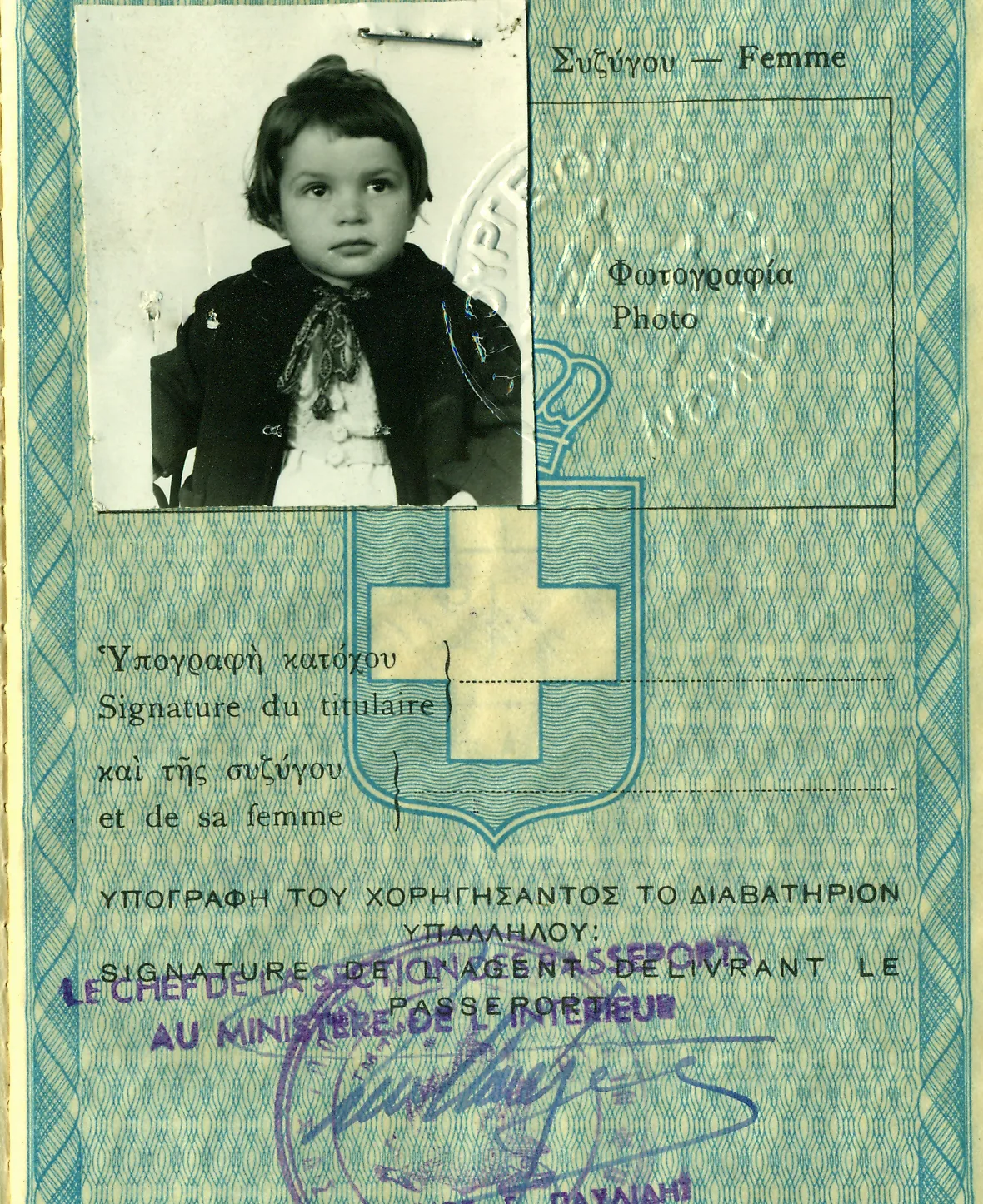

Professor Gonda Van Steen, Director, Centre for Hellenic Studies, has researched the silenced stories of the 3,200 Greek adoptees who were sent to the USA between 1949 and 1962. It was the first large-scale ‘business’ of adoption to meet increasing demand from the USA.

Their movement from Greece and their adoption were so poorly documented, and with many now in their sixties and seventies, they have some really important questions about where they come from, and no good place to start.

Professor Van Steen has been helping people get answers through her research, and despite the Covid-19 lockdown putting a hold on her travel plans, she has found the virtual element is actually helping her get more intimate stories.

“Some people fared very well, but a lot of stories were also very tragic, because a lot of these adoptions were very poorly handled.

“So a whole lot of people have this lifelong trauma with them about an unknown family, an unknown family separation in Greece, and not knowing what their lives could have been like if they had not been put on a plane to the US to meet some strangers.

“And so all these stories, as very individual stories, they need to become parts of the puzzle of Greece’s Cold War history,” Professor Van Steen explained.

Combining history (archival and oral) and creative writing, Adoption Reckonings offers the broader public a way of understanding life histories and stories in which adoption from Greece has figured prominently.

The new archives, informant pools, genres of writing, creative and artistic expressions all place pressure on the historical narrative of Greece’s 1950s ‘reconstruction’.

Other countries, too, have been grappling with their postwar international adoption histories, but Greece has postponed public and critical engagement for 70 years, said Professor Van Steen.

Watch the interview with Professor Van Steen here for more details on her research.

You can order the book here:

https://www.press.umich.edu/11333937/adoption_memory_and_cold_war_greece

Q+A/Video Transcript

Can you introduce yourself and your research project, Adoption Reckonings?

My name is Gonda Van Steen, and I teach in the Classics Department at King’s College London. My specialty is Modern Greek Studies. I am also the Director of the Center for Hellenic Studies, which is a vital component of the Arts and Humanities Research Institute.

I'm currently stuck in Houston, Texas, of all places. And I was well on my way, deep into my second project that is related to Adoption Studies. In December [2019], I published a book called Adoption, Memory, and Cold War Greece, and I was building up to do research in Greece on my second project, which is called Adoption Reckonings, this time looking much more closely at the personal histories of adoption by way of accessing the archives, most of them in Greece, and rather hard to interpret.

But that was all nice and well until Covid-19 came into the picture, and I find myself redirecting my research. My trip to Greece is of course cancelled, but I am in the United States and I'm taking advantage of this time here to contact a lot of the people who have had questions about their own adoption from Greece. They were massively sent by Greece to the United States in the 50s and in the 60s, and it's my discovery to find out that there were about 3200 of them. But this is also a history that the Greek state has never researched or never even acknowledged. So I have a lot of work to do there, too. My research has now taken on a whole novel twist. Because I'm in the same time zone and in the same geographical continent as these people, I have started to focus on what has become of their lives, their personal histories, the questions they currently have. And I know that when the Covid restrictions will be lifted, I will go back to those dusty archives, but with a completely different perspective. I will now see a real person and a real life behind every piece of paper.

What have been some of your key findings about some of these people?

Well, first of all, these adoptions were presented as emergency situations and one-off exceptions. But I found out that not only were orphans sent to America, that a total of 3200 went, with which at some point in Greece tried to meet the increasing demand of the USA. So Greece is at the very forefront of the post-war international adoption boom, which has never stopped since.

It was a shock to me to find that there are so many of them, and also that their movement from Greece and their adoption were so poorly documented. A lot of these people are now in their sixties and seventies, and so have some really important questions about where they come from, and no good place to start.

So my research is now taking on a more socially engaged dimension because I try as much as I can to educate myself on the genealogical material that is out there. But I also try to answer their questions and very specific questions that are literally coming to me from all over the world, now that people are discovering the book.

And so the questions are: ‘What can I do?’ ‘Where do I start?’ ‘I don't speak Greek, can you help?’ And my role in that project is not as much to give them the answer or lead them to their family straightaway.

My role is to give them the tools to take charge of their own search, at their own pace, and with their own input. So I see myself as a mediator in this project of searching and especially in an era when one’s biogenetic constitution, one’s endurance with an onslaught of this nasty virus, is all very much under question. I see people during the lockdown turn to their family trees, their elderly relatives, discovering stories that have long been in the family closet, unburdening themselves off a certain shame about a supposed ‘illegitimate’ child, and finally seeing their priorities differently and knowing that family has never been more important.

And if I can help out and lead people to the answers, not necessarily to their family, but to the answers and to a sense of agency in their own reconstruction of what happened in their past, I feel I have accomplished something rather important. So I'm taking a very positive look on this Covid-19 lockdown that I otherwise wouldn’t have. I feel that I may not have spent so much time with the very people whose life has been impacted; perhaps I would have hidden more behind the safety of documents, and I'm kind of glad that I'm rethinking that perspective on myself.

Has meeting these people online brought you closer to an understanding of their history and their background, do you think?

Completely! Completely! Because, first of all, there are so many stories that are all very different. It's amazing what talent people have brought to their lives, what their education has been, what their walks of life have been. Some people fared very well, but a lot of stories were also very tragic, because a lot of these adoptions were very poorly handled.

So a whole lot of people have this lifelong trauma with them about an unknown family, an unknown family separation in Greece, and not knowing what their lives could have been like if they had not been put on a plane to the US to meet some strangers.

And so all these stories, as very individual stories, they need to become parts of the puzzle of Greece’s Cold War history. And I would say they bear relevance also to the history of international adoption, which is currently very much being attacked by the adoptees themselves. Most of them of other countries like Korea or China and of a younger generation, but the adoptees all over the world are now speaking out loud and clear against international adoption. And Greece here delivers the earliest story of this phenomenon.

So do you hope your research could have a wider impact on society as a whole, and policy around international adoptions?

I certainly trust so. I see people hurting about the lack of truth, the lack of access to their documents, the lack of proper explanations as to why that happened, even today the bureaucratic obstacles that, to this day, when they’re 65 years old, prevent them from accessing what is actually accessible to bureaucrats but not to them themselves.

So I hope that the practice of let’s say emergency international adoption with very little concern for the psychology of the child, which is a life long journey, that that will drastically change, that people will think much more carefully about procedures and the lifetime impact of ‘adult’ decisions.

If and when travel lockdown restrictions ease, will you still plan to travel to Greece to meet some of the people and hear more?

I will certainly do that. It's a quick trip from London, and I like the country tremendously. And I always have a lot of work to do. I will go through with interviews I had already scheduled and had to cancel. But mainly I will look at archival research and archival material with new eyes and I will see, I will see people much more clearly and focus less on paperwork.

***