Interestingly, the second of these periods, around 85,000 years ago, was previously confirmed as having allowed expansions of our own species into Arabia, when the team discovered the first Homo sapiens fossil from Arabia in this area, dating to that time period.

Dr Paul Breeze

18 September 2020

Dramatic climate change allowed humans and elephants to walk together into the deserts of Arabia 120,000 years ago, new research reveals

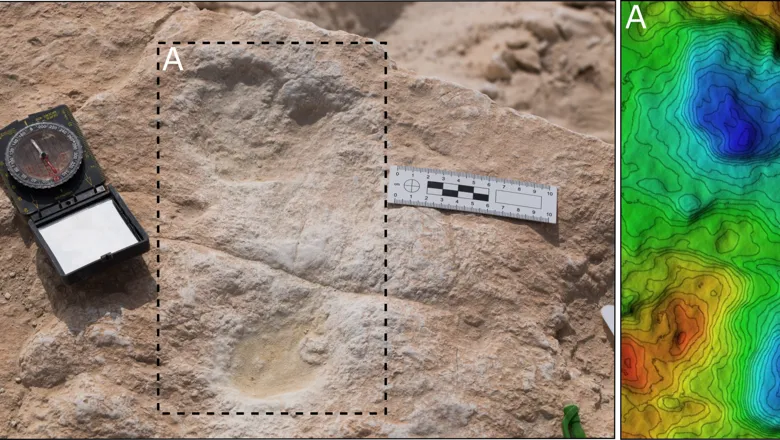

The earliest evidence yet for human and animal movement into Saudi Arabia’s Nefud Desert – fossilized footprints imprinted in the muds of an ancient lakebed – has been revealed in an academic paper.

The earliest evidence yet for human and animal movement into Saudi Arabia’s Nefud Desert – fossilized footprints imprinted in the muds of an ancient lakebed – has been revealed in an academic paper.

The research was published in Science Advances today, co-authored by King’s Geographers Professor Nick Drake and Dr Paul Breeze.

This is one of a series of new findings, in collaboration with the Max Planck Institute in Jena, that demonstrate how climate change periodically transformed the deserts into verdant grasslands via a process called ‘greening’, allowing savannah animals and different species of humans to expand from Africa into Arabia.

Dating of the site shows the tracks of footprints were created around 120,000 years ago. “This is one of two key time windows when King’s analyses have previously indicated that dense networks of rivers and lakes would have let our ancestors reach this area of northern Arabia,” said Breeze.

The footprint site (now named Alathar, or ‘trace’, in Arabic) was identified from high-resolution satellite mapping analyses performed by Dr Breeze. Following this, he and Professor Drake performed field visits – Drake to provide geological and geomorphological interpretation of past landscapes, while Breeze (an archaeologist and palaeogeographer by training) provided detailed 3D mapping of sites and their finds using highly precise GPS units and drones, and helped to excavate these.

Paul’s systematic satellite mapping has identified the remains of thousands of lakes and rivers that formerly existed across Arabia, and links these to records of past climate change. Across dozens of sites similar to Alathar, the emerging picture is one of repeated opportunities for our species to move into Arabia, as African animals moved into newly green and wet environments. ‘Greening’ occurred due to cyclical variations in the Earth's orbit and axis, and their influence on the global monsoon systems.

The team has now investigated dozens of these ancient lake beds over eight years of expeditions into the Arabian deserts, allowing specialists in diverse areas to examine the rich archaeological and environmental records the deposits provide.

Since 2011 the King’s Geography Department has been a partner on these projects in Arabia, run by Professor Michael Petraglia of the Max Planck Institute in Jena, and made possible due to a long term collaboration between the Saudi Ministry for Culture, Saudi Geological Survey, King Saud University in Riyadh, and an international project team. Similar mapping work has now been performed across the Sahara, and is also being performed for the Asian deserts as part of a Leverhulme grant awarded to Dr Breeze, again partnered with the Max Plank Institute, for which fieldwork in the Mongolian Desert commenced last year.

Read the full text journal article.