29 August 2019

Justice can only be done when we have equal representation in the judiciary

Oliver Martin

OLIVER MARTIN: A new dataset on women’s representation in Supreme Courts across the world shows we are far from gender parity, but progress is being made.

This is part of a blog series from undergraduate and master's students who participated in internships and work experience schemes at the Global Institute for Women's Leadership.

Speaking at an event to commemorate 100 years since women gained the right to enter the UK’s judiciary, Britain’s first ever female President of the Supreme Court claimed that women should make up “at least”’ half of all UK judges. This target shouldn’t be too far off given that the pipeline for the legal profession is heavily female dominated – with over two-thirds of law undergraduates women. However, the further up the UK’s court system you go, there are fewer and fewer women – at the very top in Lady Hale’s Supreme Court, only 25% of judges are women.

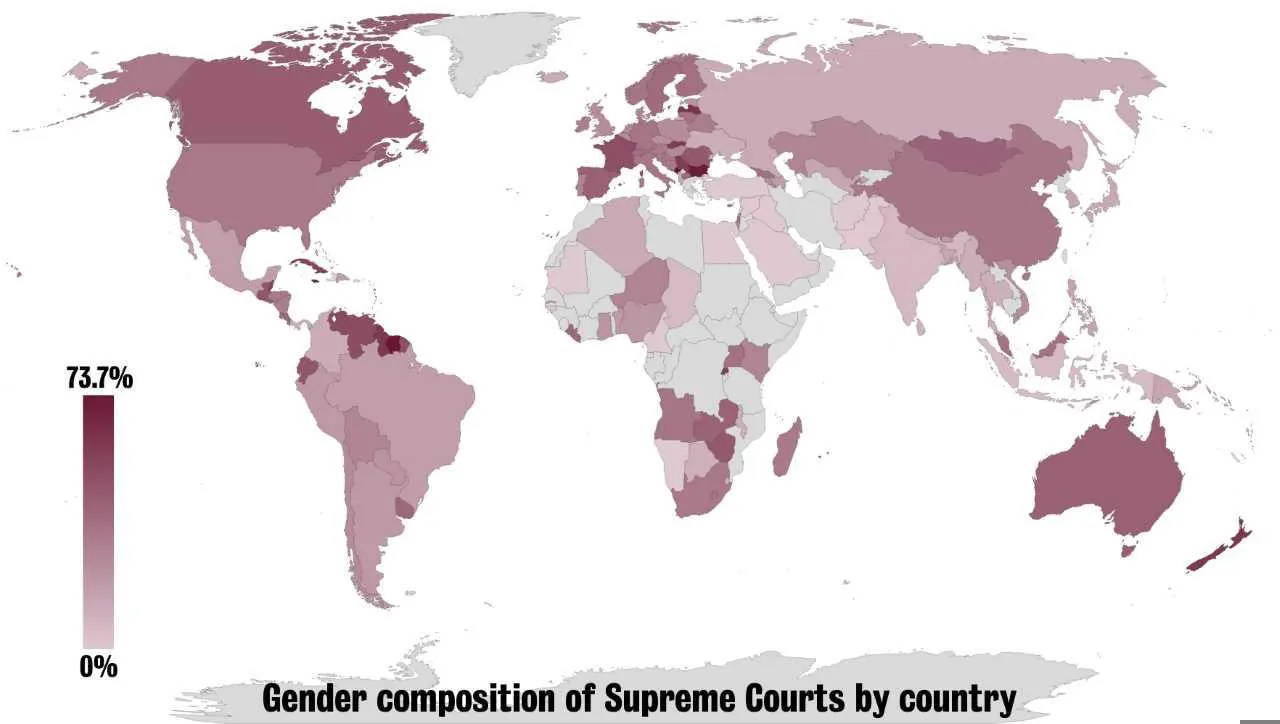

The gender imbalance in Britain’s Supreme Court is far from unique. New data I collected during my internship at the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership offers a comprehensive and up to date look at women’s representation in Supreme Courts across the world. 71.8% of the average country’s Supreme Court bench is made up of men and only 28.2% of judges are women.

The dataset I produced is by far the most comprehensive look at women’s representation on Supreme Courts to-date, with 145 countries covered using the most recent information available. The above chart shows the proportion of female Supreme Court justices by country, ranging from 17 countries that don’t even have one woman on their Supreme Court bench, to Suriname and Montenegro where women constitute almost 74% of the bench. Britain’s bench – with 25% of women judges – ranks in the bottom half of countries (78th out of 145). However, it is only one of 34 countries (23.4% of countries in total) that has a woman at the top of its judiciary. For most countries, this constitutes the final drop-off in women’s representation vertically in the judiciary. For example, in China 38.6% of regular judges in the Supreme Court are female, but amongst the President and Vice President positions women are two and a half times less likely than men to occupy the top spots.

The impact of female judges

Research has shown that the gender composition of Supreme Court benches can affect their decision-making. A study found that female judges are more likely to find in favour of the plaintiff in sexual harassment and sex discrimination cases. It also revealed that the gender of judges was a better predictor of their decision than even their political ideology. Male judges’ decisions were also shown to be impacted by the genders of those around them: when on a panel with female judges they were more than twice as likely to decide for the plaintiff than on an all-male panel.

The gender makeup of the Supreme Court also influences decisions on non-gender related cases. Research has found that women tend to vote more liberally than men on areas of the law not viewed as “women’s issues” even when controlling for political ideology, and the presence of a female judge can cause male judges to vote more liberally. Gender composition can sway the decision a Supreme Court makes: it is startling to consider how many court cases would have reached opposite decisions had there been even one woman on the bench.

That said, a high-female presence is no guarantee of women’s legal protection. The Italian judiciary recently made worldwide news after a rape case was thrown out when a judge concluded from a photo that the purported victim was “too masculine” for the accused to have wanted to rape her. Paradoxically, this decision was made by an all-female bench of judges.

Are we making progress to a more gender-equal bench?

Whilst the proportion of women in many of the Supreme Courts in the world remains low, there is potential optimism to be gleaned from the data. Firstly, when compared with the largest comparable study – a UN Women report from 2011 – the rate of women on the judiciaries of countries that featured in both datasets rose from 24.0% to 30.9% - a rise of 29% in less than a decade.

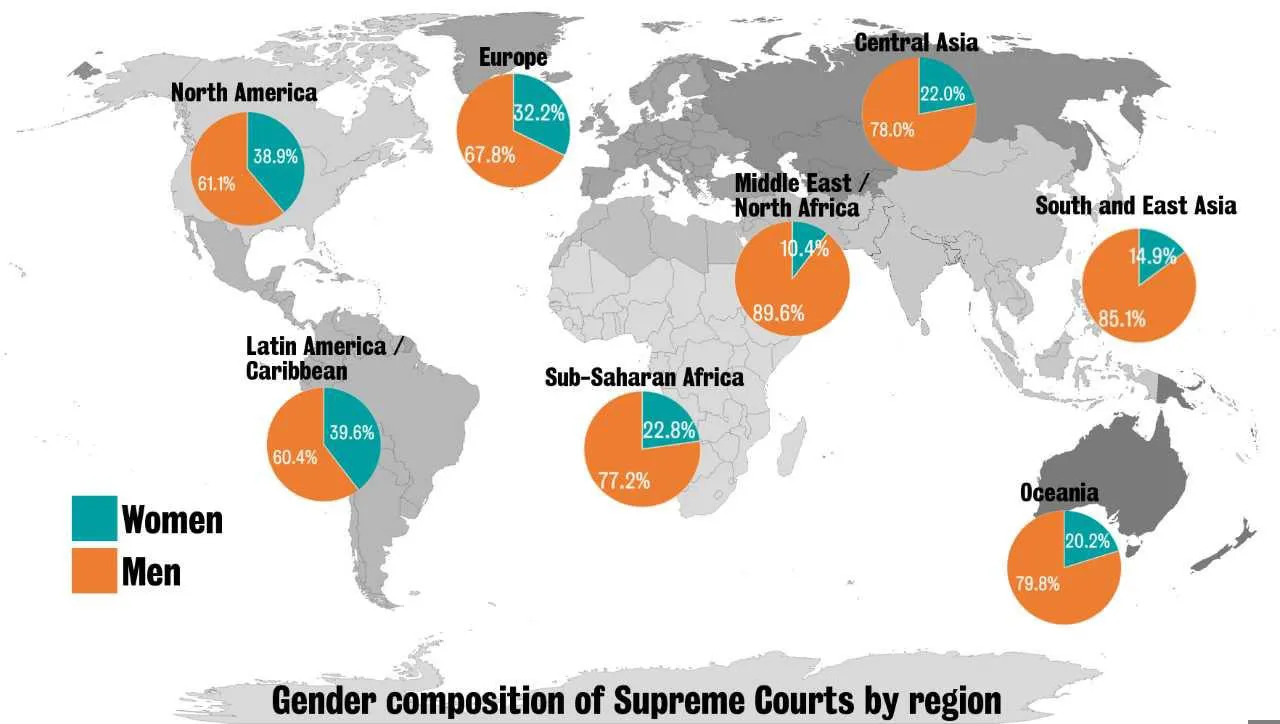

The academic literature on women’s political representation offers insights into this fairly rapid growth. Critical mass theory suggests that the initial chunk of progress that takes women from constituting a handful of token positions to forming a sizeable minority (at around 30%) is a much slower and harder fought process than the progress from 30% to 50% – so we might see a more rapid increase once countries attain 30%. However, for many countries throughout Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia that are nowhere near the critical mass, parity in the judiciary is likely to be a long way off.

It may also be the case that efforts towards progressing gender equality in countries such as Britain may simply be yet to materialise. Supreme Court justices, typically appointed for life after a storied career, tend to be older with an the average age of 67. Slow steps towards furthering women’s equality have been made over 100 years since women gained the right to enter the legal profession in Britain, and so women’s reduced presence on the Supreme Court in part reflects historic sexism. In the younger generation, a promising 50% of judges under 50 in the UK are women – hopefully this will translate up the hierarchy.

Ultimately, whilst there are solid signs of growth towards parity in some countries, the steps towards equal representation are slow and not always linear. The fact that women only constitute 28.2% of Supreme Court judges globally is likely both a symptom of an unfair system but also a factor that reinforces it. Speaking on the matter, the former Chief Justice of Utah Justice Christine M, Durham said women judges “bring an individual and collective perspective to their work that cannot be achieved in a system which reflects the experience of only a part of the people whose lives it affects”. In short, for true justice we need a judiciary which reflects society.

Oliver Martin is a master’s student in Public Policy at King’s College London and interned at the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership in spring 2019.