23 October 2019

New research reveals when the spark starts to fade in VC co-investment partnerships

Professor Igor Filatotchev, Corporate Governance and Strategy

A new study from King's Business School, UCL and ABS shows how the benefits of venture capital firms ‘partnering up’ to co-invest on a regular basis fades over time.

A new study shows how the benefits of venture capital firms ‘partnering up’ to co-invest on a regular basis fades over time. The research by Professor Igor Filatotchev of King’s Business School, Joost Rietveld of UCL School of Management and Cristiano Bellavitis of Auckland Business School found that, on average, the tipping point when the benefits of trust and routine started to lapse into complacency and over-confidence, was 67 co-investments among all co-investors.

The research analysed 4,550 US ventures in key knowledge-intensive sectors which had received syndicated investments during a nearly 40 year period.1 It found that that the likelihood of a co-investment by the same VCs achieving a successful exit through IPO or M&A was 8.4 per cent when the VCs had never previously co-invested, and rose to a peak 11.3 per cent chance of a successful exit at around 70 co-investments. After that point, the chances of a successful exit fell by 30 per cent to an eight per cent chance of success when the partners shared 150 prior co-investments.

Professor Filatotchev explains: “the probability of a successful outcome from a co-investment partnership was actually lower when VC firms had conducted a very high number of co-investments with each other than if they had never worked on a deal together before. The positive relationship becomes too easy: trust, ease of decision making and sharing the burden of due diligence become complacency and reduced post-deal monitoring.”

“Gradually, the shared deal history also means that networks that might initially overlap start to coincide almost completely, so that there is a much smaller selection of potential investments to pick from.”

“We know from other contexts that overly close relationships can eventually become group-think: these findings give VCs an idea of when the warning lights should start flashing and they should think about finding a mix of familiar and unfamiliar co-investors to improve their chances of success.”

The research also details how the impact of a co-investment relationship, and the tipping point at which familiarity starts to become over-familiarity, are dependent on two key factors:

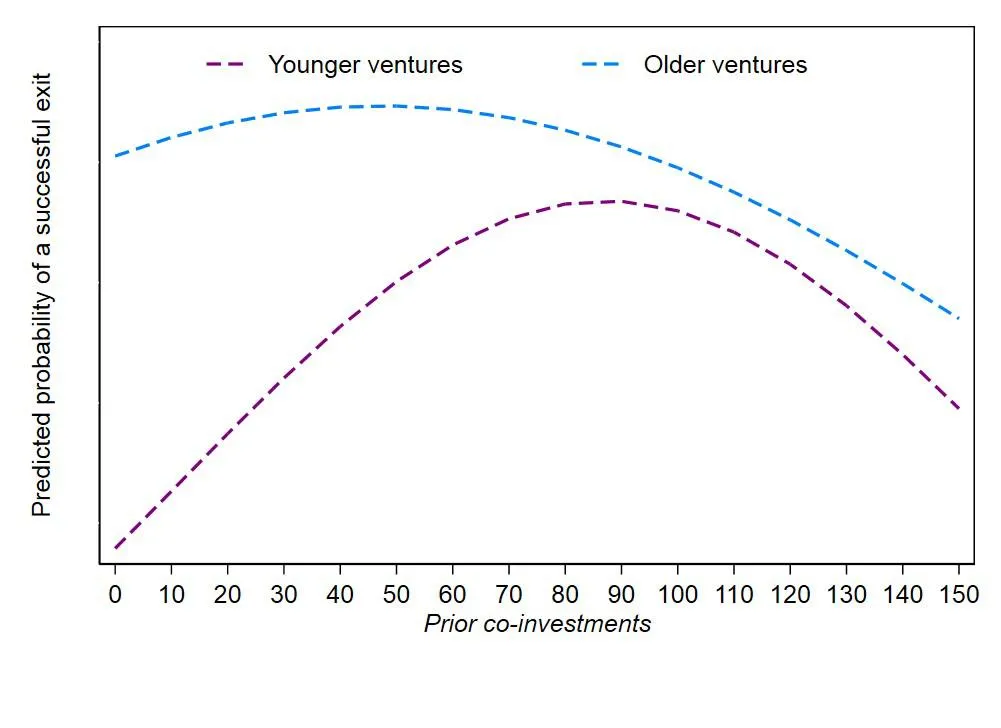

The age of the business invested in: initially, building a co-investment relationship has a more marked impact on the chances of a successful exit for partners investing in earlier stage ventures. For investments in earlier stage ventures, a track record of previous co-investments has the potential to almost double the partners’ probability of achieving a successful exit. For investments in newer ventures, VCs on their first co-investment are predicted to have a 5.6 per cent chance of a successful exit, rising to a peak 11.3 per cent chance of a successful exit.

The benefits of retaining the co-investing relationship typically also lasted longer in partnerships focussed on newer ventures than those focussed on older ventures. The tipping-point between an increasing and declining impact on the chances of a successful exit is predicted to occur after around 90 co-investments for newer ventures, and just 50 co-investments in older ventures. By around 50 co-investments in older ventures, the marginal effect of the co-investment relationship on the chances of a successful exit is likely to be negative.

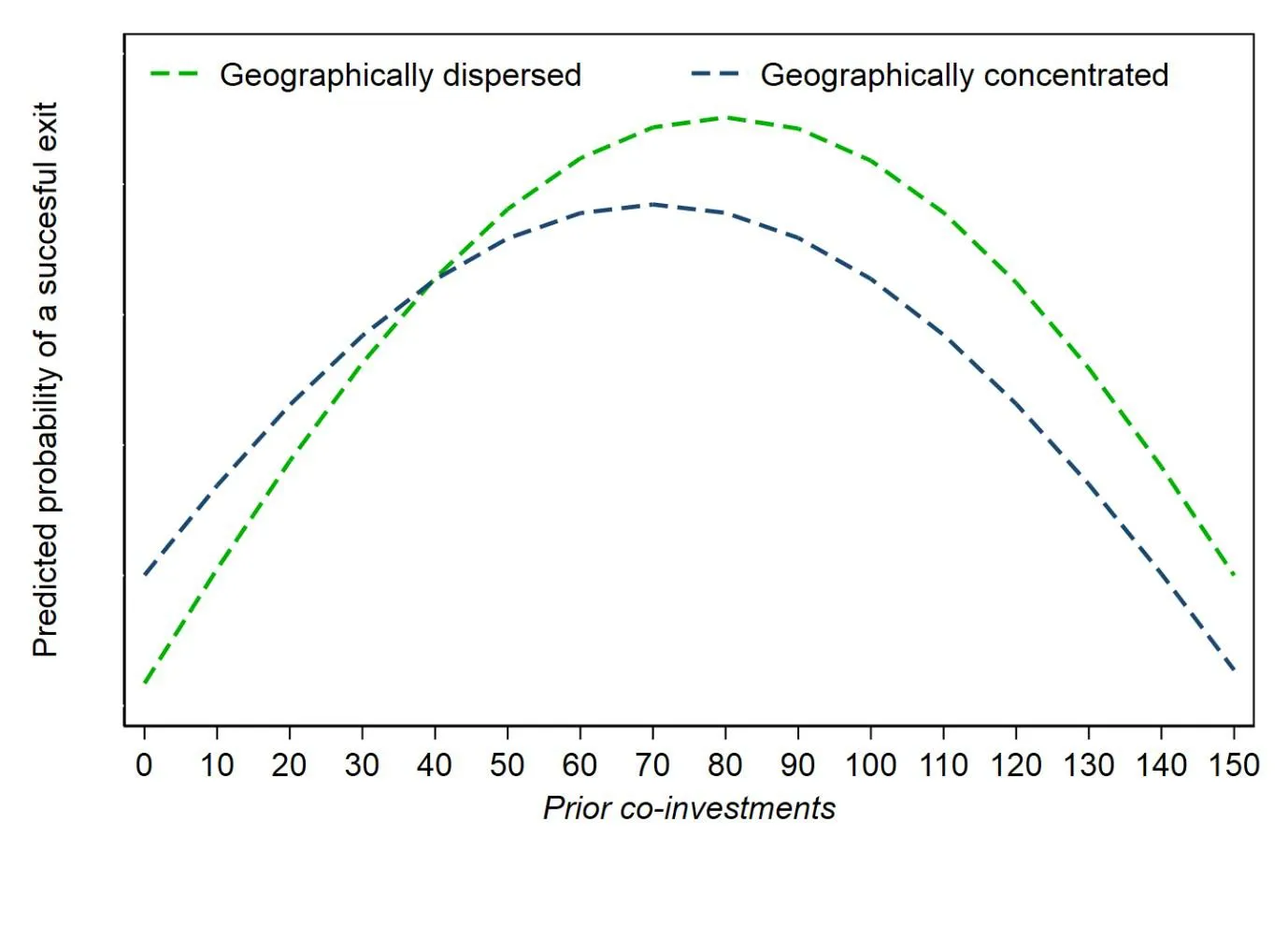

The physical proximity of co-investing syndicates: On average, geographical proximity among co-investors does not affect the chances of achieving a positive exit. However, the initially positive impact that repeated co-investment has on the probability of a positive exit is more muted for geographically concentrated syndicates than for geographically dispersed ones.

For geographically concentrated syndicates the likelihood of a successful exit increases by 30 per cent from a nine per cent chance of a positive exit at zero prior co-investments, to a peak of an 11.8 per cent chance of a successful exit at 70 co-investments. By comparison, prior experience of co-investing with each other increases geographically dispersed syndicates’ chance of success by up to 50 per cent, rising from a predicted 8.2 per cent probability of a successful exit where the partners had no established co-investment relationship, to 12.5 per cent at 80 prior deals. For geographically concentrated syndicates, the positive effects of co-investment tailed off and become negative more quickly on the downward curve.

Adds Professor Filatotchev: “this may be because when co-investors are located close to each other, the greater chances of success come mainly from the physical ease of doing business rather than because the partners have truly built a strong relationship through the process of working together. When the impact of geography fades, the partners then have fewer other advantages to fall back on. They will also have some specific problems, like the fact that there are no efficiencies to be gained from sharing monitoring responsibilities based on travel times.”

1. The study looked at investments in ventures in the medical, health, life science, computer hardware and software and semi-conductor industries. It defined a VC syndicate as two or more VC firms taking an equity stake for a joint pay off, either in the same investment round, or in different rounds.