My group studies how pancreas cells, in particular pancreatic beta cells, are formed. With the explosion of spatial transcriptomics in recent years, we jumped at the opportunity to use these techniques to map the individual cell types in the pancreas and to learn how they develop and interact over space and time.

Professor Francesca Spagnoli, Professor of Regenerative Medicine at King’s College London and corresponding author of the paper.

27 November 2025

Research reveals how cells organise to build the pancreas

New research from King’s College London shows how different cell types develop, assemble and interact to build a functioning pancreas.

By showing how pancreatic cells organise themselves across development in mouse models, the research provides a blueprint for modelling the pancreas in the lab and could open new avenues for developing therapies for pancreatic diseases such as diabetes.

Understanding how organs are built

Organ function depends not only on the many different cell types within a tissue but also on how those cells are arranged in space and how they interact — from individual cells to the larger structures that form the complete organ.

While scientists have made progress in identifying pancreatic cell types, much less has been known about how these cells are positioned in the pancreas, how they assemble, and how they work together during development.

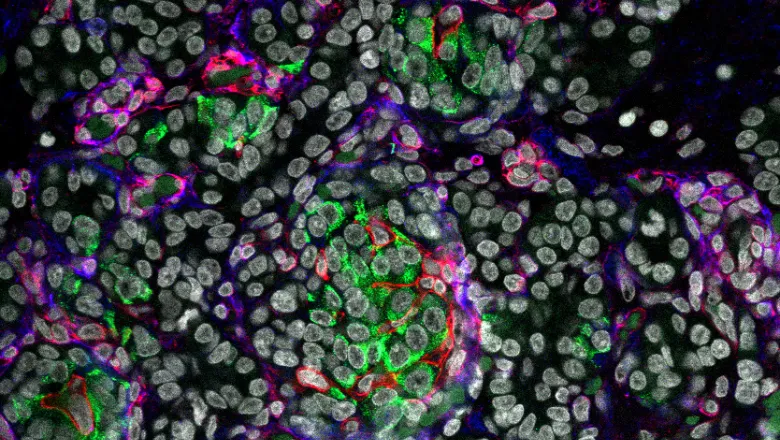

To address this, researchers led by Professor Francesca Spagnoli at King’s used single-cell and spatial transcriptomics to look at pancreas tissue from mice at different life stages. These techniques reveal which genes are active in each individual cell and the precise location of each cell within the tissue.

Using this information, the researchers then used computational approaches to build detailed maps of pancreatic cells in mice from embryo to adult. These maps showed the different cells that make up the pancreas, the nearby supporting cells that create the local communities (or ‘cellular niches’) where cells interact, and how early cells arrange themselves as the pancreas develops.

The research also found that the pancreas is organised into two distinct cellular niches, which reflect the two main functions of the pancreas: the exocrine niche, which contains cells that aid digestion, and the endocrine niche, which contains insulin-secreting beta cells, which help to regulate blood glucose. Within the endocrine niche, a special supporting cell type creates a stable environment around beta cells throughout life - the researchers saw this in the mouse models, as well as in subsequent experiments with human tissue.

Overall, the research shows how different cells develop together to form organised, fully functional pancreatic tissue.

Recreating pancreatic environments in the lab

To understand the functional importance of these niches, the researchers used human pluripotent stem cells (cells that can develop into almost any cell type in the body) to recreate pancreatic microenvironments in the lab. When they exposed the stem cells to components of the endocrine niche, the stem cells were far more effective at developing into insulin-producing beta cells. This highlights that cell arrangement and the surrounding environment are as important as cell identity when trying to recreate tissues outside the body.

Why this matters for diabetes research and therapy

These insights could significantly improve how scientists model pancreatic diseases, including diabetes, in the laboratory. By understanding how cells are positioned and supported within the pancreas, researchers can build more accurate models which could be used to develop more effective therapies to treat pancreatic diseases.

“Our research could improve how scientists model diabetes in the lab and help develop better stem cell-based therapies aimed at restoring or replacing beta cells, a potential step toward curing diabetes,” Professor Spagnoli adds.

The research was supported by a Wellcome Investigator Award and by the EU H2020 FET-Open Pan3DP project.

Read the full paper in Science Advances.