02 May 2019

In 2007, the Indian Government introduced a National Health Insurance Scheme, aimed at providing subsided quality healthcare to the poorest 40% in India. However, enrolment rates for the scheme are low, particularly amongst those that need it the most. Dr Sanchari Roy from King's finds that the Indian caste system may be one of the reasons behind this.

In the UK, it is taken for granted that healthcare is available to everyone for free via the National Health Service (NHS). But in many countries private companies provide healthcare, meaning that it’s only accessible for those who can afford to pay for it.

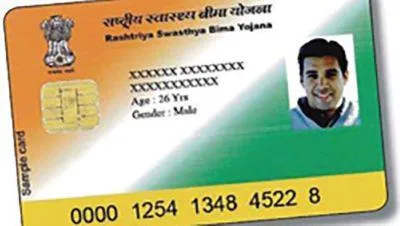

In 2007, the Indian Government introduced a National Health Insurance Scheme, aimed at providing subsidised quality healthcare to the poorest 40% of India’s population. However, enrolment rates for the scheme have remained low, particularly amongst those that need it the most.

It appears that a lack of awareness of such welfare schemes may be limiting how much they are used.

To understand how to build better awareness of the scheme amongst the target demographic, Dr Sanchari Roy from the Department of International Development has been researching the constraints to information flow in India and has found that social barriers related to the Indian caste system may be a blocker.

The cost of caste?

The caste system in India is one of the world’s oldest forms of surviving social classification. Despite an official ban in 1948, discrimination based on caste is still prevalent today. However, Dr Roy and co-authors have discovered that financial incentives could help to overcome social barriers and entrenched caste prejudice when it comes to accessing healthcare.

Dr Roy and her team employed local women in the state of Karnataka in southwest India to visit families and create public awareness of the National Health Insurance Scheme amongst those for whom the program was intended.

One agent was employed per village and, while all agents were paid to do this job, some randomly selected agents were given the additional incentive of a small payment depending on how well the beneficiary households scored on a follow up knowledge test about the healthcare scheme. This meant that the researchers could identify whether financial initiatives for agents were effective in improving information flow.

The results showed that financially incentivised agents improved beneficiary knowledge of the scheme and achieved higher subsequent enrolment rates. In fact, interviews with beneficiaries found that compared to their non-incentivised counterparts, these agents spent less time on people of similar caste, education and poverty status, and more time with those different to themselves – ensuring these beneficiaries understood the scheme well and knew how to enrol.

Dr Roy explains, ‘It appears that this incentive payment pushed the agents to engage with people of all castes and encourage them to enrol in the healthcare scheme.

‘If the agent wasn’t incentivised, but was from different caste than the beneficiary, enrolment rates were lower.

‘This suggests that, without a financial incentive, people may simply prefer not to interact with people from different castes. This is the common ‘preference’ story that is cited in literature, but we now want to test this.’

What next?

A follow-up project will test whether this ‘caste cost’ is a result of entrenched prejudice, or whether it is the result of communication barriers, such as the varying dialects across the castes.

The hope is that the findings are will assist policy design on a national level and help to overcome the negative consequences of poor information flow between castes, especially in relation to accessing healthcare.

Read the full research: https://academic.oup.com/ej/article-abstract/129/617/110/5237196?redirectedFrom=fulltext

Delivering the UN Sustainable Development Goals

King's College London has a long and proud history of serving the needs and aspirations of society. We are committed to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a university, and we use them as a framework for reporting on our social impact. The SDGs are a set of 17 goals approved by the 193 member states of the United Nations (UN) which aim to transform the world by 2030. This research supports SDGs 1 and 3.