We wanted to understand how cyclophilin inhibitors work by using human-derived models, which are a better representation of the reality of alcohol-induced liver disease in humans than animal models or cell lines.

Dr Elena Palma, Principal Investigator and adjunct Lecturer in the Roger Williams Institute of Liver Studies and co-senior author of the study

21 August 2025

Drug reshapes tissue architecture to reduce damage in alcohol-related liver disease

A new study has shed light on how a type of drug works to reduce liver damage in alcohol-related liver disease, by reshaping the architecture of the tissue. The findings could pave the way for the development of new treatments for liver disease and improve outcomes for patients.

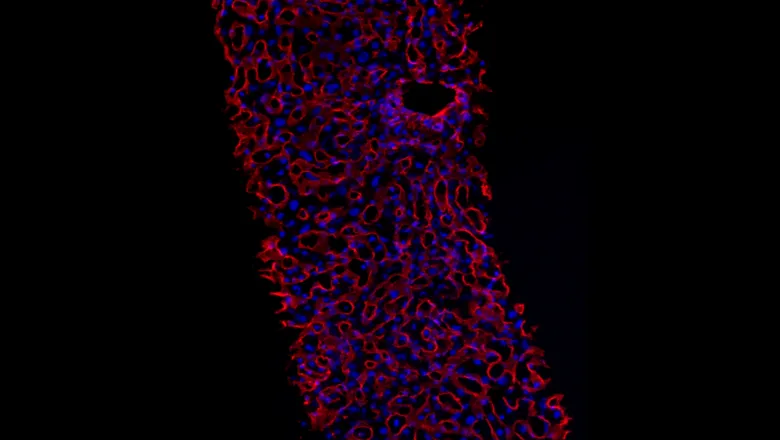

Researchers from the Roger Williams Institute of Liver Studies at King’s College London developed two 3D models from human tissue to understand the effects that a drug – a cyclophilin inhibitor – has on liver tissue damaged by alcohol. They found that the drug stops the build-up of proteins responsible for making the tissue stiff – a characteristic of liver disease – allowing the liver to remodel itself back to a healthier state.

The findings from the study, funded by the Foundation for Liver Research and Hepion Pharmaceuticals, were published in the British Journal of Pharmacology.

Addressing a knowledge gap with human-derived models

In the UK, more than 11,000 people die from liver disease each year.1 A characteristic of liver disease is fibrosis – where repeated damage to the liver, such as through excess alcohol intake in alcohol-related liver disease, causes healthy liver tissue to be replaced by scar tissue. As a result, the liver becomes stiff and loses its ability to function. If left untreated, fibrosis can lead to permanent liver damage.

Previous research has found a group of proteins called cyclophilins to be involved in fibrosis, and blocking these proteins with drugs called cyclophilin inhibitors has shown promise in early phase clinical trials for some types of liver disease. But how exactly these drugs work, and whether they work for alcohol-related liver disease, has been unclear.

To address this knowledge gap, the team – led by Dr Elena Palma, Dr Luca Urbani and Professor Shilpa Chokshi – created 3D models of liver disease using human liver tissue. The tissue samples were collected from patients at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust who were undergoing surgery to remove liver tumours.

“There are currently no approved therapies for the treatment of alcohol-induced liver disease, and people with this type of liver disease are often not included in clinical trials for new therapies,” said Dr Elena Palma, Principal Investigator and adjunct Lecturer in the Roger Williams Institute of Liver Studies and co-senior author of the study.

Using segments of patient samples that were tumour-free, the researchers created thin slices of liver tissue to study in the lab. They then exposed the liver slices to alcohol to mimic the damage caused to the liver after excess alcohol consumption, before treating them with a cyclophilin inhibitor.

By studying the genes and proteins within the treated liver slices, the team found that the drug reduced fibrosis in the tissue by stopping the build-up of structural proteins that cause the liver to become stiff.

Using a second model, the team were able to track down where exactly these protein changes were happening. The second model looked specifically at the cells in the liver responsible for driving fibrosis – stellate cells. Using the same patient liver samples, the team isolated stellate cells and ‘activated’ them in the laboratory to imitate what happens in alcohol-induced fibrosis. Then they treated the cells with the cyclophilin inhibitor.

Using the two models, the team confirmed that the drug reduced fibrosis by changing the three-dimensional organisation and type of structural proteins produced by the stellate cells. These changes ultimately reshaped the architecture of the damaged tissue.

The experimental work was carried out by joint first authors of the study Una Rastovic, PhD student, and Dr Sara Campinoti, postdoctoral researcher.

The value of researcher-clinician connections

The findings suggest that the use of cyclophilin inhibitors could offer a promising approach for treating fibrosis in alcohol-related liver disease. As the study used human tissues, the findings are more likely to be translational and valuable for patients, the authors say.

A strength of this study is that it’s all based in human-derived liver tissue. Access to this type of tissue is very rare in the lab – and this approach is possible because we are part of a multidisciplinary department where scientists have close connections with clinicians.

Dr Luca Urbani, Principal Investigator and adjunct Senior Lecturer in the Roger Williams Institute of Liver Studies and co-senior author of the study.

The researchers hope their findings will attract more interest from drug companies to develop cyclophilin inhibitors and pave the way to testing these drugs in clinical trials in people affected by alcohol-related liver disease.

References

- British Liver Trust. Liver disease in numbers – key facts and statistics. Available at https://britishlivertrust.org.uk/information-and-support/statistics/ (accessed on 12 August 2025).