30 September 2025

Societal inequality linked to structural brain changes in children

Income inequality in society has been linked to structural changes in the brains of children who go on to experience poorer mental health.

A King’s College London study is the first to reveal how an unequal distribution of wealth in society is associated with altered connections and reduced surface area in the brains of children. Published in Nature Mental Health today, the research also linked these changes with poorer mental health outcomes.

Despite evidence that individual wealth impacts brain development, this is the first time societal inequality has been linked to changes in the developing brain.

Dr Divyangana Rakesh, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King’s College London, said: “This isn’t just about individual family income – it is about how income is distributed in society. Both children from wealthy and lower-income families showed altered neurodevelopment and we established that this has a lasting impact on wellbeing.”

Scientists believe living in an unequal society amplifies feelings of status anxiety and social comparison, disrupting levels of cortisol – a hormone linked to stress. This places strain on the brain and other organs, potentially accounting for neurodevelopment changes.

The team used data from over 10,000 children aged 9-10, across the United States. This was gathered from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, a large-scale developmental neuroimaging resource.

They measured inequality by scoring how evenly income is measured in society – giving a score of 0 for ‘perfect’ equality, where everyone has the same income, and 1 for inequality – where one person has all income and everyone else has nothing. Most states and countries sit somewhere between these values.

States with higher inequality included New York, Connecticut, California and Florida. By contrast, Utah, Wisconsin, Minnesota and Vermont were among the most equal, with narrower income gaps.

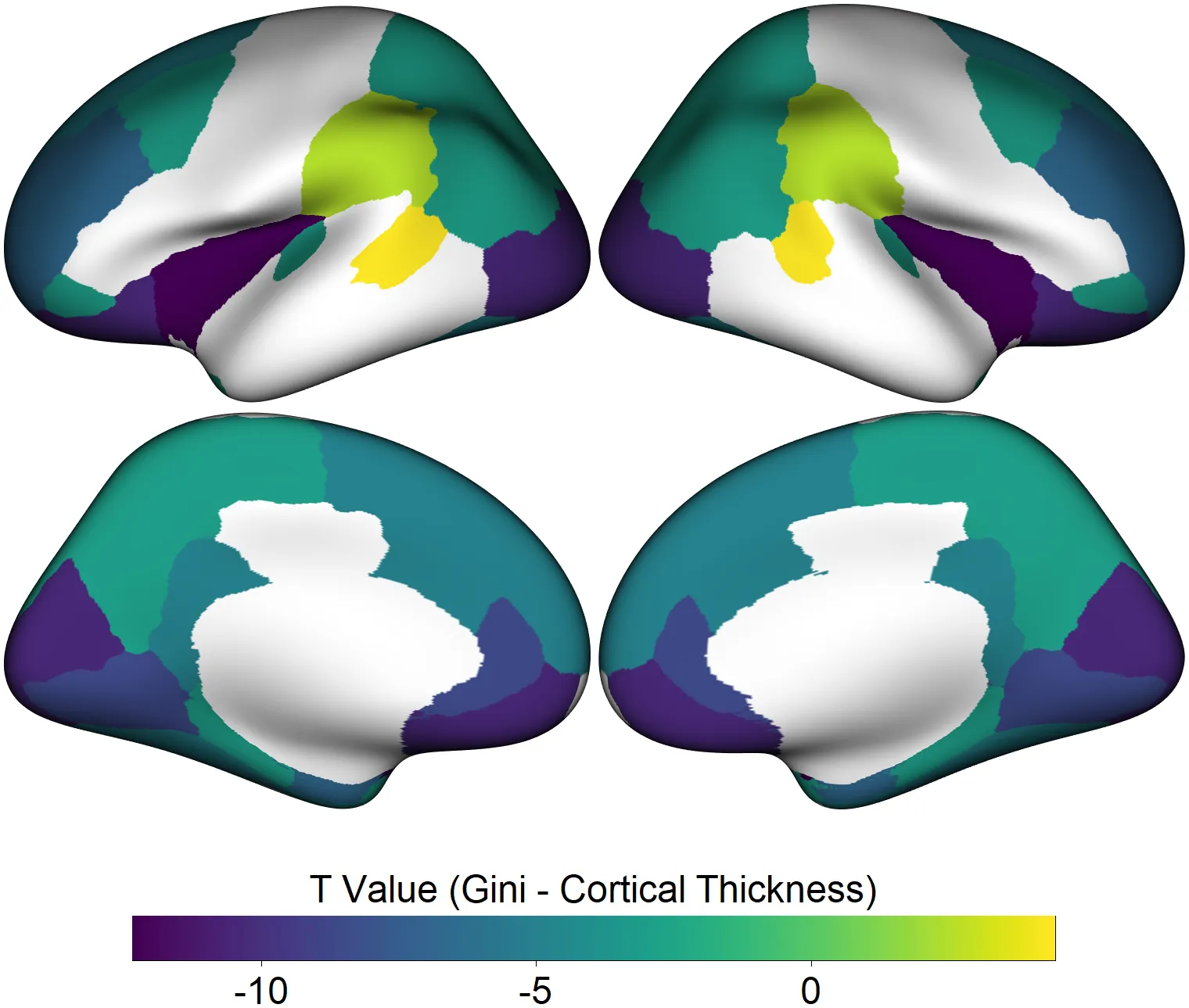

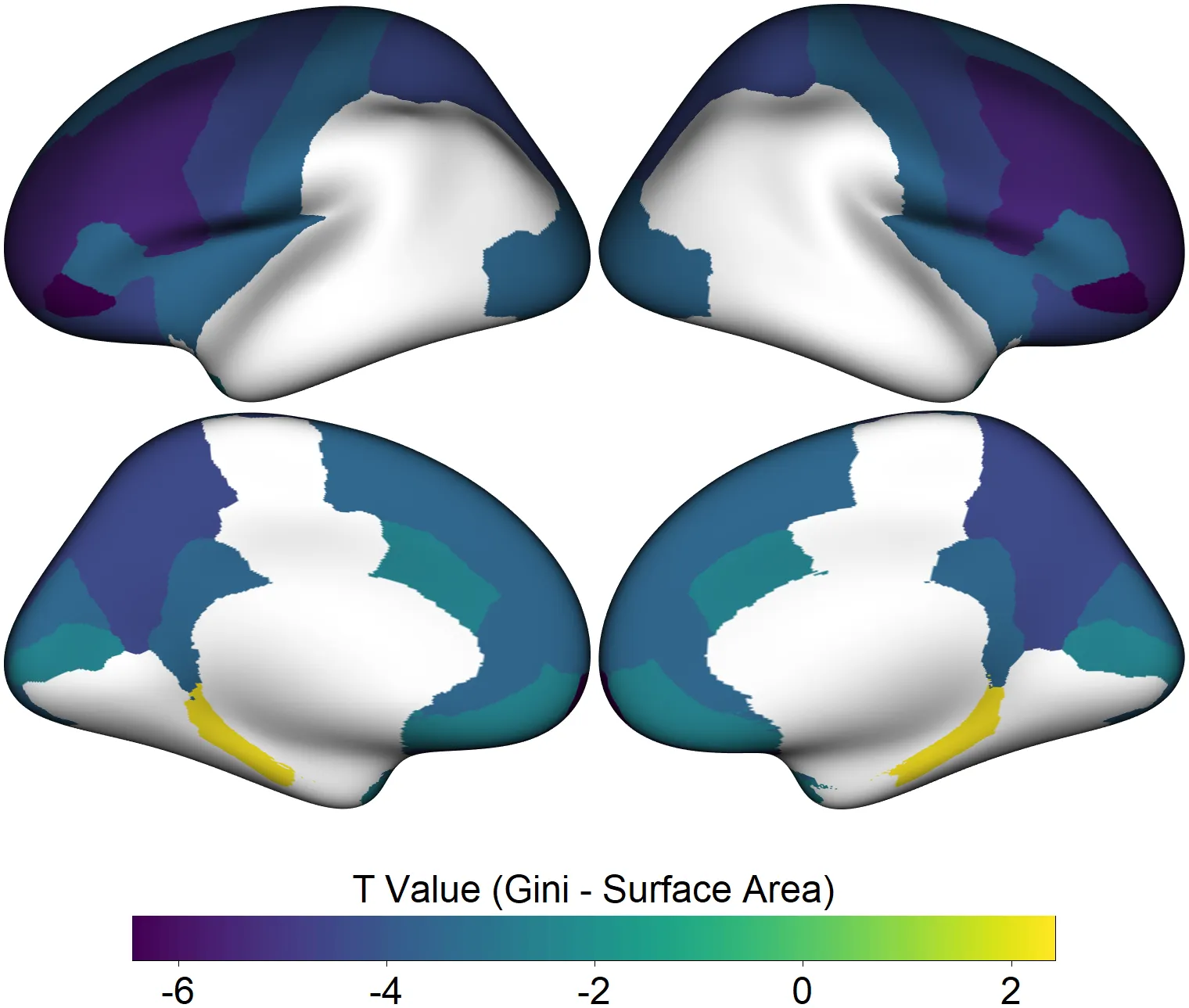

MRI scans were analysed to study the surface area and thickness of regions in the cortex including those involved in higher cognitive functions like memory, attention, emotion and language. They also examined connections between different regions of the brain using MRI scans, where changes in blood flow indicate brain activity.

The scans showed children living in areas of higher levels of societal inequality associated with reduced surface area of the cortex and altered connections between multiple brain regions. These findings provide evidence of impacted neurodevelopment, which might relate to future mental health and cognitive function.

The researchers then investigated how these neurodevelopmental changes might impact mental health. They analysed data from questionnaires aimed at revealing mental health symptoms such as depression and anxiety, at ages 10 and 11 – six and eighteen months after the MRI scans were taken.

Mental health outcomes were significantly worse for those who had lived in a society with unequal distributions of wealth. The researchers found that some of the brain alterations served as a pathway linking inequality and later mental health – inequality was associated with structural and functional alterations in the brain which, in turn, were associated with worse mental health.

Dr Rakesh said: “We are interested to see how these findings compare around the world. For example, several areas in the UK are characterised by high income inequality. London exhibits significant inequality, with both very rich and very poor residents. Future research could examine income inequality in the UK at the level of counties and boroughs to investigate whether similar effects are observed.”

Co-author Professor Vikram Patel, Harvard University, said: “These findings add to the growing literature which demonstrates how social factors, in this instance income inequality, can influence well-being through pathways which include structural changes in the brain.”

Co-author Professor Kate Pickett, University of York, said: “Our paper emphasises that reducing inequality isn't just about economics – it's a public health imperative. The brain changes we observed in regions involved in emotion regulation and attention suggest that inequality creates a toxic social environment that literally shapes how young minds develop, with consequences for mental health and impacts that can last a lifetime. This is a significant advance in understanding how societal-level inequality gets under the skin to affect mental health.”

The research team believe that implementing policies to reduce societal inequality could help to promote healthy neurodevelopment.

Dr Rakesh added: “Progressive taxation, increased social safety nets, and universal healthcare could help alleviate the stressors that disproportionately affect children in more unequal societies. Community-building initiatives and investments in public infrastructure could also mitigate the detrimental effects of inequality by promoting trust and social cohesion.”

Read the study: https://www.nature.com/articles/s44220-025-00508-1

This study was supported by funding from the Brain and Behaviour Research Foundation, the UKRI Medical Research Council and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the ABCD study (https://abcdstudy.org) held in the NIMH Data Archive.

Population health researchers across King's focus on tackling the burden of health inequalities to influence health policy, improve healthcare delivery, and create a healthier, more equitable world.