A Taste of Christmas

In a light-hearted experiment in the spirit of Christmas, experts from the Dental Institute tested ways to banish the bitterness of Brussels sprouts.

How you perceive the bitterness of Brussels sprouts is related to both biochemistry and genetics. The chemicals responsible for the bitterness of Brussels sprouts are glucosinates, which bind with different bitter taste receptors on the tongue. There are some receptors that not all people possess, due to the absence of the gene for a particular type of bitter receptor called TAS2R. Lacking this bitter receptor can reduce the bitterness of vegetables like Brussels sprouts by 60 per cent.

One way to reduce bitterness is to cook the sprouts with alternative flavours. Chilli and mint are commonly found in recipes. Both of these flavours are spices also known as TRP agonists.

Transient receptor potential (TRP) channel agonists are a group of chemicals often associated with spices. Familiar TRP agonists include capsaicin, menthol, and cinnamaldehyde, found in chilli, mint and cinnamon. The TRP channels are activated not only by these chemicals but by temperature too. So the hot feeling you perceive when eating a spicy curry is because the same channel is being activated as if your mouth was actually hot.

There are three main TRP channels involved with the detection of these agonists; TRPV1 (activated by high temperatures and chilli), TRPM8 (activated by cold temperatures and menthol) and TRPA1 (activated by cinnamaldehyde and very cold temperatures).

‘There are many recipes that include TRP agonists in the preparation of Brussels sprouts and we hypothesized that this is because TRP agonists reduce the bitter intensity of Brussels sprouts, making them more palatable,’ says Dr Guy Carpenter, Reader of Oral Biology at the King’s College London Dental Institute.

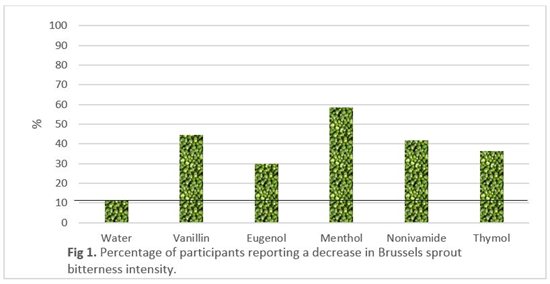

Since boiling accentuates the bitterness of sprouts, the researchers microwaved Brussel sprouts for three minutes. They then cut them in half and asked 12 participants to eat one half before a 30-second mouth rinse with one of five TRP agonists and the other half afterwards, each time rating the bitterness intensity of the sprout on a visual analogue scale.

The five TRP agonists were vanillin (from vanilla), eugenol (from cloves), menthol (from mint), nonivamide (a capsaicin analogue to that found in chilli), and thymol (from thyme).

Although the researchers found some variation between people in how they perceived changes in bitterness after the mouthwash, most of the mouthwashes reduced the bitterness intensity, with menthol and nonivamide being the most effective.

’The reason we see a reduction in bitter intensity after a TRP agonist mouthwash may be due to temporal dominance of the TRP agonists’, says Jack Houghton, a PhD student at the Dental Institute. ‘In other words, the agonist may be distracting your attention from the bitterness. So the relatively intense perception of the coolness after the menthol mouth rinse or spiciness of the nonivamide may be overriding some of the bitterness of the sprouts.’

‘Of course the main ingredient to have with such small studies as ours is a pinch of salt,’ adds Dr Carpenter. ‘Happy eating!’

Jack Houghton is studying for a PhD “Sensory effects of TRP channel agonists on salivary secretion” at the King’s College London Dental Institute.

Table 1

| TRP Agonist | Found In | TRP Channel |

|---|

| Vanillin |

Vanilla |

TRPV3 |

| Eugenol |

Cloves |

TRPV1 |

| Menthol |

Mint |

TRPM8 |

| Nonivamide (a capsacin analogue) |

Chilli |

TRPV1 |

| Thymol |

Thyme |

TRPA1 |