Promising target for triple-negative breast cancers

Promising drug target for aggressive 'triple-negative' breast cancers identified

Promising drug target for aggressive 'triple-negative' breast cancers identified

Scientists from Breast Cancer Now’s Research Unit in the Faculty of Life Sciences & Medicine, in collaboration with the charity Tony Robins Research Centre at the Institute of Cancer Research have identified a molecule crucial to the growth of ‘triple-negative’ breast cancers that they believe could now be targeted by drugs to help treat patients resistant to chemotherapy.

Around 15 per cent of all breast cancers are ‘triple-negative’, a particularly aggressive form of breast cancer found more commonly in younger women. The name refers to the fact that they lack the three receptors which are normally used to classify breast cancers: the oestrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2).

This form of breast cancer therefore cannot be treated with targeted drugs commonly used to interfere with these receptors, such as tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors for ER and PR-positive breast cancer, or Herceptin for HER2-positive disease. It can often only be targeted by chemotherapy, which works well for some but leaves others with few remaining options if their cancers become resistant to the treatment

The study, published on Monday 24 October in the journal Nature Medicine, recognises the role of a molecule called PIM1 in driving and controlling ‘triple-negative’ breast cancers, influencing the ‘death threshold’ of cancer cells in the face of treatments such as chemotherapy.

This new research – led by Professor Andrew Tutt in the Faculty's Division of Cancer Studies and The Institute of Cancer Research – has discovered that in the majority of triple-negative breast cancers, the molecule PIM1 has been hijacked and is being over-produced, helping the cancers survive by making them more resistant to these ‘death signals’.

The finding provides some explanation as to why a significant group of ‘triple-negative’ breast cancers are very aggressive and resist the effects of chemotherapy.

Professor Andrew Tutt, Director of the Breast Cancer Now Toby Robins Research Centre at the Institute of Cancer Research and the Breast Cancer Now Research Unit at King’s College London, said:

'It is early days but as PIM1-inhibitor drugs have already been discovered they may give us a new way to hit these cancer genes. The hope would be that these drugs could strip triple-negative breast cancers of their defences so that they can be pushed over the cliff by other breast cancer treatments.'

An independent study from researchers in San Fransico, also published in the same issue of Nature Medicine, confirmed the importance of PIM1 in ‘triple-negative’ breast cancer. The discovery could see PIM1-inhibitors put into trials to triple negative breast cancer within two years.

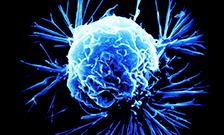

Image: Breast cancer cell. ALFRED PASIEKA/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Notes to editors

For further information please contact Public Relations on pr@kcl.ac.uk

For further information about King's, please visit the King's in brief web pages