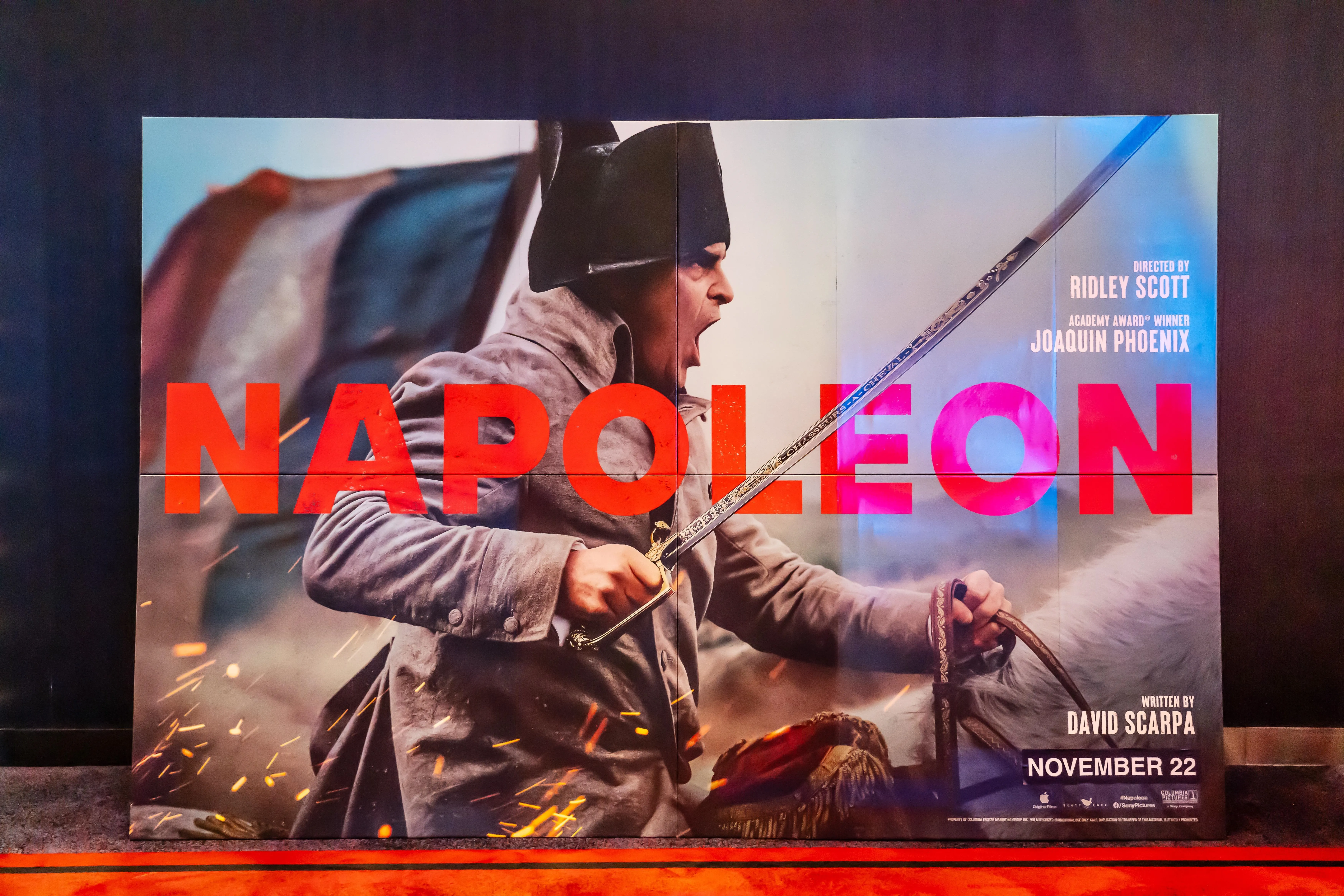

Banner in a cinema theatre in Bangkok, Thailand

Banner in a cinema theatre in Bangkok, Thailand

Instead of Napoleon the weirdo, we should have been treated to either a villain or a hero. Given today’s sensibilities around race and gender, one might have expected treatment of Napoleon as the classic political villain: the ultimate example of the corruption of power, resulting in the destruction of a liberty-affirming republic in favour of a repressive empire. Josephine’s dumping in favour of Marie-Louise of Austria (grandniece of Marie Antoinette, no less), might at a stretch have served as a metaphor for this Darth Vaderesque transition, as indeed it did to an extent for contemporaries. A second, more intriguing and for our age also pertinent interpretation, might have portrayed Napoleon as a kind of radical centrist hero, struggling to bring together a traumatised society polarised by two extremes. It’s not quite clear how Josephine could have fitted in here, beyond the fairly obvious one as an impediment to durability given her inability to produce an heir.

French historians unsurprisingly dislike Ridley Scott’s film. They see it as yet another Anglo-Saxon outrage, in the tradition of great cartoonists like Gillray and Cruikshank who at the time belittled Napoleon mercilessly. This criticism of Scott is a bit unfair, given that the British in general and Wellington in particular don’t come across that sympathetically either. But the larger problems with the film are undoubtedly stark: a confused storyline, disjointed and undeveloped scenes, and that fatal lack of authenticity when it comes to Napoleon’s world. What a missed opportunity!