What is Factoid Prosopography all about?

First off, Factoid Prosopography is an approach to doing Prosopography. So, we need to start by thinking about what we mean by Prosopography itself. To get us started, here is a quote from the introduction by Averil Cameron for her book Fifty Years of Prosopography dating from 2003.

History-writing is made out of all kinds of components, but information about individual persons remains among the most important. A story without persons would not be history at all. And even a Marxist Historiography of class depends on persons to give it life. Prosopography — ‘writing about individuals’, or ‘the recording of persons’–is one methodology which gathers and digests information about the individual persons who are attested in a particular historical period; as well as uncovering specific careers and relationships, it may also provide a tool for the broader detection of historical trends.

(p xiii)

Cameron was an active partner in the earliest of King’s College London (KCL) structured data prosopographies: the Prosopography of the Byzantine Empire, but her book draws on the tradition of prosopography that predates the digital world and started with Theodor Mommsen in the 19th century. A great deal of useful insight into the issues that prosopography raises for history can be gained from starting here. However, for our purposes here something important is said through implication in this introduction when Cameron classifies prosopography as one of a kind of “history writing”, and defines Prosopography itself as the act of “writing about individuals”: the implication being that it, like the vast preponderance of historical research products even now in the digital age, is expressed as writing: as prose text.

Indeed, here is one of the significant differences between what was thought of as prosopographical research output from, say, the 1990s and before, and the various prosopography projects that were undertaken by KCL’s Centre for Computing in the Humanities, now Department of Digital Humanities (CCH/DDH) that all contributed to the development of an understanding of factoid prosopography. For the factoid model grew out of a new conception of prosopography which was based on a structured data orientation, rather than the writing of historical prose. Indeed, the factoid model first arose in the mid 1990s from the re-conception of the Prosopography of the Byzantine Empire from a then conventional article-oriented print publication into a data-oriented one. As a result of this quite radical re-conception of PBE, it became quickly evident that a substantial rethinking of what constituted this prosopographical work was necessary. In particular, the articles – writing about individuals – that had made up much of the work on PBE up to that time – had to be unpicked, at least to some extent, into database structure. What were the major entities and relationships between them that would make up this structure? Persons and Historical Sources as database entities were obvious: this was a prosopography, after all. However, for prosopographical work that drew on a broad range of types of sources from personal letters to legal documents, what other consistent structure was available that both covered such a diverse range of sources, and that also made sense as an element of a prosopography? After some thinking by members of the PBE team at the time; in particular Gordon Gallacher and Dion Smythe; it became evident that structure could emerge from the references themselves to people in the various primary sources. It was from this that the idea of the factoid arose, described in some detail in Bradley and Short 2005.

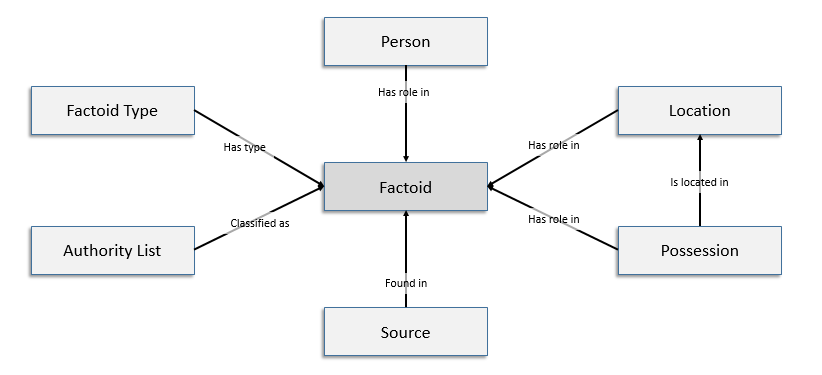

The essential idea of the factoid can be seen in this simplified schematic diagram:

… and which has been put into words as “A factoid is a spot in a source that says something about a person or persons.”

We will see in the formal ontology for factoid prosopography elsewhere on this site that this figure is a simplified version of the full factoid model. Even so, as the schematic suggests, the factoid acts as a structural nexus that connects together historical sources, persons (and person assemblages acting as persons), places and possessions, and various kinds of classification schemes (such as personal relationships, titles and offices, etc). CCH/DDH’s factoid prosopography projects each generated tens of thousands of factoids.

CCH/DDH has carried out, collaboratively with various historian partners, the creation of a good number of structured prosopographies based on the factoid model. You can see more about them at the page Factoid Prosopographies at CCH/DDH KCL in this site. Although these prosopographies had in common the CCH/DDH staff (myself, and developers), they were not approached as if a single conception could be simply applied, without alteration, across all of them. The different historical periods they represented, the different nature of the sources, and the different academic interests of our historian partners meant that, although they all used the base factoid approach as the basis for representation of the research output, they also differed from each one in various ways. Even so, the factoid model has proven to be fundamental to all of them, although the details about how the factoid model has varied between them. There is information about the role of the factoid model in the representation of three of them in Bradley et al 2019.

From an historiographical point of view, the use of the factoid model has a profound impact on the intellectual nature of a prosopography: it affects the scholarly design and concept of the prosopography rather fundamentally.

To see this we return to Cameron’s concept of prosopography and narrative mentioned briefly earlier. The methodological model that Cameron presupposes, that of “story” and “writing” has been significantly altered in the highly structured, data oriented, factoid prosopographical datasets. Whereas the process of writing articles about people in traditional prosopography puts the act of historical interpretation into the work of prosopography at the level of the person through the moulding of materials into a story about the person presented in the person’s article, factoids do not provide a mechanism that, on their own, directly supports the act of historical interpretation in this way. Instead, historical interpretation happens at the level of the individual assertions made by the historical sources. A factoid prosopography user is not presented with a story about the person, but a collection of factoid-assertions that the user must assemble into her own story. There is a perspective on this issue in (Bradley 2020).

References

Bradley, John and Harold Short (2005). “Texts into databases: the Evolving Field of New-style Prosopography” in Literary and Linguistic Computing Vol. 20 Suppl. 1:3-24.

Bradley, John (2020). “Creating Historical Identity with Data: a digital prosopography perspective”. In Horstmann, Jan et al (ed). Towards Undogmatic Reading: Narratology, Digital Humanities and Beyond. University of Hamburg Press (forthcoming).

Bradley, John, Alice Rio, Matthew Hammond and Dauvit Broun (2019). “Exploring a model for the semantics of medieval legal charters”. In International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing. Volume 13 No. 1-2. pp. 136-154. Online DOI:10.3366/ijhac.2017.0184

Cameron, Averil ed. (2003). Fifty Years of Prosopography: The Later Roman Empire, Byzantium and Beyond. Oxford: Oxford University Press.